Diplomacy

The New Geopolitical Landscape in The EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood: Fragmentation of Economic Ties Post-February 2022

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Diplomacy

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Sep.28,2023

Nov.10, 2023

The EU’s Eastern neighbourhood is now more fragmented than ever when it comes to the countries’ relations with Moscow. The Russian full-scale and genocidal invasion of Ukraine brought about a change in the EU’s relations with Ukraine and Moldova which received the candidate status. Their membership talks with the EU are expected to start soon, pulling both countries further away from Russia. Georgia, however, remains for now at the door due to democratic backsliding, although the majority of its population supports accession to the EU. Tbilisi’s relations with Kyiv have turned increasingly sour due to its more than-ambivalent reaction to the full-scale invasion. Armenia’s relations with Russia have become more ambiguous. Albeit having lost confidence in Moscow as its main security provider, it helps Russia to evade the Western sanctions. Azerbaijan, in the meantime, has gained from the EU’s re-orientation of energy imports and acted as an independent player, wishing to maximise its benefits yet not being able to present a viable alternative to Russia gas for the European markets. Belarus’ relations with Russia appear more straightforward – i.e., collaboration in the invasion of Ukraine and Minsk’s growing dependence on Moscow. At first glance, one can see that the geopolitical landscape is being reshaped. In the following, this analysis takes a closer look at what those countries’ foreign trade with Russia can tell about this evolution and the Russian leverage in the region.

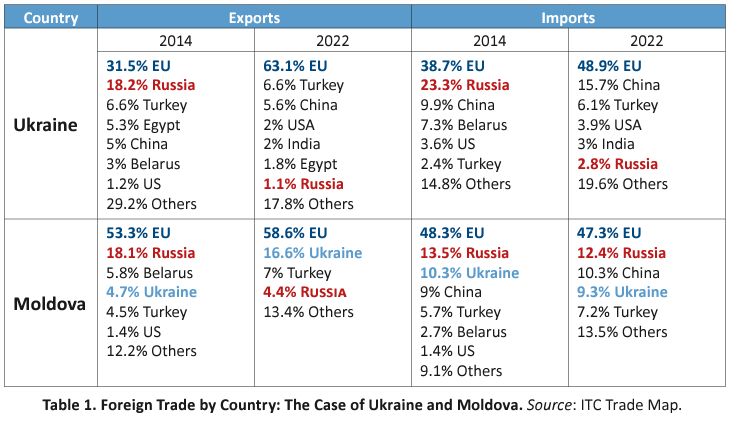

The share that Russia used to claim in Ukraine’s foreign trade shrank radically, falling to 1.1% for exports and 2.8% for imports against 5% and 8.4% in 2021, respectively. One-fifth of those imports are linked to the energy sector and, most likely, to gas transit as Ukraine reached self-sufficiency in the winter of last year, owing to the decrease in gas consumption. At the same time, according to the SecDev Group, 12.4 trillion USD worth of Ukraine’s energy deposits, metals, and minerals have fallen under Russian control due to the occupation of the Ukrainian territory.

With the Russian blockade, Ukraine’s foreign trade has collapsed, while exports to overseas partners like China or India have shrunk.8 Ukraine has, therefore, had no choice but to turn to the European Union and find new markets to ensure its survival. Ironically for Russia, the EU member states (Poland and Romania in particular) have become by far Ukraine’s biggest trading partners. Exports to the EU reached 28 billion USD in 2022 (26.8 billion in 2021), which represented 63.1% of total exports (up from 39.4% in 2021). Imports from the EU accounted for 26.9 billion USD in 2022 (28.9 billion USD in 2021), which equalled 48.9% of the total volume (up from 39.8% in 2021). Having lost all forms of political capital and economic influence in Ukraine, Russia can only resort to the destruction and looting of its national resources. Moldova’s import indicators have remained relatively stable since 2014. What stands out from the data, however, is that the share of exports to Russia shrank from 8.8% in 2021 to 4.4% in 2022. This is partly explainable by the Kremlin’s fruit embargo on Chisinau, which used to be Moldova’s most important export to Russia. In contrast, the share of Moldova’s exports to Ukraine has risen dramatically: from 3% in 2021 to 16.6% in 2022. Its exported value to Ukraine grew from 92 million USD to 720 million USD, whereas the total value of Moldova’s exports increased by around 1.2 billion USD. Hence, Ukraine accounts for around 60% of the increased value, making it the second-largest foreign trading partner behind Romania/EU. Moldova’s main exporting sector to Ukraine is mineral fuels, oils, and distillation products (81.25% or 587 million USD out of the total of 720 million USD), which has to do with the fact that natural gas is being backhauled from the EU to Ukraine via Moldova. The European Union – and especially Romania – remains in the first place. In 2022, the EU’s share in Moldova’s exports and imports stood at 58.6% and 47.3%, respectively. Moscow can still turn Chisinau’s economic dependence into political leverage – to a certain extent – by fuelling the economic crisis through halting gas shipment and thus influencing the prices, which could provoke discontent in Moldova’s Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia in particular. Similarly, the Kremlin can employ its two main proxies – the Party of Socialists and the ȘOR Party – for the same purpose, with a view to the upcoming 2024 presidential and the 2025 parliamentary elections. Moldovan authorities are already preparing to mitigate the Russian energy leverage not only by buying electricity from Romania and requiring the distributors to stockpile natural gas but also by countering the Kremlin propaganda and aligning with EU media regulations.

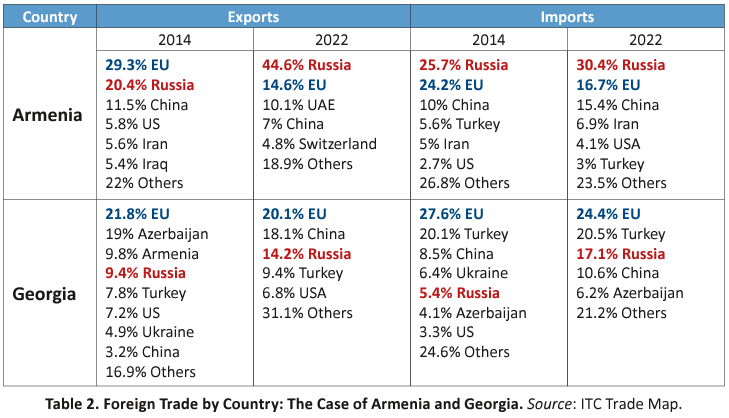

Tbilisi’s relations with Moscow are best described as ambivalent. After an initial downgrade in exports and imports following the Russian invasion in 2008, both have been growing for over a decade. Russia’s share in Georgia’s imports reached its maximum since 2005 in 2022: 15.4% and 17.1%, respectively. However, Russia’s share in Georgia’s exports has slightly dropped down to 14.2%. The European Union remains Georgia’s biggest trading partner, accounting for 20.1% of its exports and 24.4% of its imports. Russia’s use of dependencies to leverage foreign countries has been in the experts’ spotlight for a long time. Most recently, the Georgian office of Transparency International highlighted that the money coming to Georgia from Russia through remittances, tourism, and exports in 2022 was three times higher than in 2021 (mainly due to the soaring remittances). In 2022, it amounted to 14.6% of Georgia’s GDP, whereas this figure represented only 6.3% in 2021. Moreover, the Kremlin has gained new forms of leverage – e.g., through the acquisition of 49% of Petrocas Energy – since Irakli Garibashvili came back to power, reinforcing the trend of Russia’s growing share in Georgia’s foreign trade. Separately, Georgia has been trying to benefit from the war and thus intensifying its economic contacts with the Kremlin, thereby weakening the anti-Russia front and the sanction regime. The aforementioned facts help build the case for classifying the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) as pro-Russian. They are also being interpreted as the GD’s attempt to consolidate its power ahead of the 2024 parliamentary elections. Regardless of the academic debate about the political nature of the government’s intentions, Georgia finds itself in a complex and risky situation of strategic ambiguity as the figures suggest.

Yerevan’s relationship with Moscow has also been quite ambivalent, especially since last year. Russia was Armenia’s first trading partner, accounting for 44.6% of its exports and 30.4% of its imports in 2022. In a long-term perspective, Armenia has been increasing its dependence on Russia for nearly a decade already. Back in 2014, the EU was still Armenia’s number one trading partner with export and import shares of 29.3% and 24.2%, respectively. Nonetheless, worth noting is a (radical) change that occurred between 2021 and 2022, especially with regards to exports. The value of exports to Russia increased from 793 million USD to 2.3 billion USD. This spike was due to re-exports to Russia from Western countries in line with the Kremlin’s “parallel imports” strategy. Not only does Armenia help Russia circumvent the sanctions but also tries to benefit from the invasion by increasing its trade, as well as attracting and facilitating the re-settlement of Russian IT businesses. For years, Armenia has been trying to balance between Russia and other partners in the context of the war with Azerbaijan. Amidst the war in Ukraine, Azerbaijan’s blockade of the Lachin Corridor and the lack of Russian engagement, Armenia finds itself in a tricky position. A huge tension remains between Armenia’s willingness to diversify its foreign policy away from Russia – towards the EU among others – and its tight relationship with Moscow that still enjoys many leverages through defence, energy, and economy. Nevertheless, Yerevan’s willingness in itself indicates that Russia has been losing traction in the South Caucasian state. Furthermore, Armenia’s recent decision to send its first humanitarian aid to Ukraine raises numerous questions as some might see it as another balancing act or a new foreign policy failure for Russia.

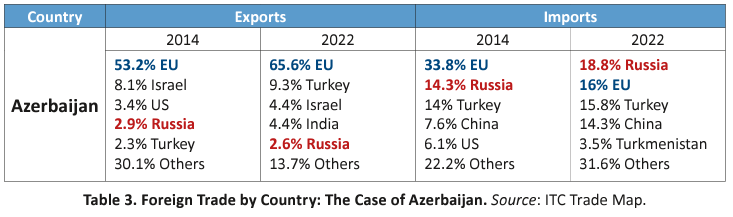

When it comes to Azerbaijan’s foreign trade with Russia, the figures have not changed dramatically. An increase in Turkey’s share in Azerbaijan’s foreign trade is perceptible, and so are the share and value of exports to the EU (58.8% or 13 billion USD in 2021 against 65.6% or 25 billion USD in 2022). The figures, however, further indicate that Baku has also diversified its import partners. For instance, China has experienced a breakthrough. Russia remains Azerbaijan’s first import market (18.8%), followed by the EU (16%), Turkey (15.8%), and China (14.3%) within the same range. Unlike other countries in the EU’s Eastern neighbourhood, Azerbaijan does not depend on Russian energy for its consumption. Furthermore, Baku benefits from the war by enjoying a huge boost in revenues, owing it to the EU’s reorientation of energy trade partners after the full-scale invasion. Azerbaijan remains a key player in the region, able to shape the rules of the geopolitical competition due to its relative independence from other countries. Overall, Russia does not enjoy an economic leverage substantial enough to allow it to influence Baku’s foreign policy course. One might prefer to read their bilateral relations through the context of the war in Nagorno-Karabakh. Some see such a “deepening” as potentially putting Armenia, the West, and Ukraine at risk. The blockade of the Lachin corridor that has isolated and trapped around 120 000 ethnic Armenians inside Nagorno-Karabagh, with dire humanitarian consequences, speaks against any rapprochement with the West, and so does Baku’s increasing military cooperation with Moscow. The fact that Azerbaijan is forced to import gas from Russia in order to meet its obligations to Europe is another worrying development, not to mention its suspected aid to Russia to avoid sanctions. One may argue that, in 2022, Azerbaijan kept a low foreign policy profile, choosing not to vote on the UNGA resolutions condemning Russian aggression. This is in line with other signs pointing to the long-term cooperation – if not friendship – between those two countries.

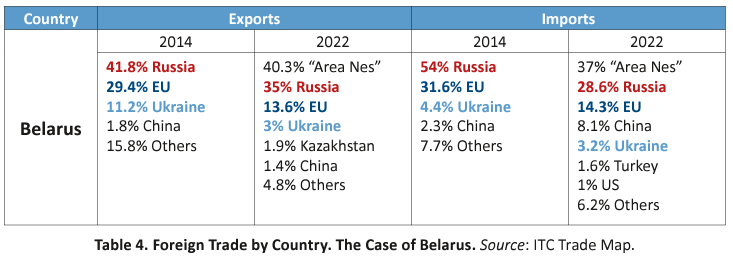

Belarus is indubitably the country where Russia managed to keep strong ties and leverages. In addition to letting Russian troops be stationed on its soil, thus opening the way for the full-scale invasion, there is evidence of Lukashenka’s involvement in the forced deportation of at least 2 100 Ukrainian children to Belarus. When it comes to Belarus’ foreign trade with Russia, the ICT database will hardly be of great use, considering the lack of reporting from 2022 and the impossibility of fully grasping what was hidden under the “Area NES” category in 2021. Furthermore, one would be prudent to doubt – to a certain extent – the official government figures in light of Belarusian officials’ tendency to conceal information, as showcased by Lev Lvovskiy. Nonetheless, by looking at Belarus’s foreign trade, one can draw the conclusion that its “multi-vector” economic policy is dead. Following the violent political repressions domestically, Western sanctions, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Belarus has lost both the EU and Kyiv as main trading partners. Minsk has lost almost all its exports to Ukraine (5.5% of Belarus’ GDP), while trade with the EU has more than halved following Russia’s invasion – third and second places, respectively. The contraction of Belarus’ trade with the West and the closure of the Ukrainian market pushed Belarus to turn even more towards Russia and, to some extent, China. Different estimates put Russia’s share in Belarus’s foreign trade within the 60% – 70% range in 2022. In fact, this might have more to do with higher prices (due to the devaluation of the Belarusian Ruble), rather than an increasing trade volume according to the Eurasian Development Bank. Furthermore, Russia made its market available to Belarusian exports and loaned 1.7 billion USD for the import substitution programme; Belarus’ debt servicing payments have also been delayed until 2027-28. Therefore, Belarus funds the efforts to mitigate recession by increasing dependence on the Russian market. Belarus’ economic stability is “directly linked to Russia’s macroeconomic standing” according to Kamil Kłysiński from the OSW. Finding economic niches in non-Western countries and rogue states is the only way for Belarus to limit its dependence on Russia.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and its consequences are reshaping the geopolitical balance of the EU’s Eastern neighbourhood region. • Ukraine has no choice but to purify itself from Russian politico-economic influence and leverage and turn to the European Union in order to survive. • The picture is clear under Moldova’s current government, which is now embracing a Euro-Atlantic course and trying to wean off Russian politico-economic influence. • The Georgian government tries to benefit from the war while dangerously sliding towards pro-Russian authoritarianism and causing an increase in tensions with both Ukraine and the Euro-Atlantic community due to this position. • The Georgian government tries to benefit from the war while dangerously sliding towards pro-Russian authoritarianism and causing an increase in tensions with both Ukraine and the Euro-Atlantic community due to this position. • Azerbaijan is a player of its own kind that enjoys positive relations with the Kremlin and helps it to bypass sanctions, as its other South Caucasian neighbours do as well. • Belarus not only willingly paved the way for the Russian invasion and participated in many crimes Russia committed in Ukraine but also became even more dependent on Moscow. The fact that Russia managed to retain – or even increase – its more or less strong level of politico-economic clout in some of the countries and influence their economic choices highlights hardened lines of division in the foreign policy strategies of the six countries and increased fragmentation of EU’s Eastern neighbourhood more broadly.

First published in :

Master’s student at Sorbonne Nouvelle University

Arthur Leveque is a master’s student in European Studies from Sorbonne Nouvelle University. After a year at Tartu University studying both the so-called post-Soviet space and EU foreign policy issues, he is now focusing on French and EU relations with Ukraine, especially when it comes to the enlargement of the European Union.

Picture Credit: ICDS

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!