Diplomacy

Leveraging India’s Arctic Observer Status: Scientific Diplomacy as a Lever for Climate, Resource and Security Advancement

Image Source : Google Maps

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Diplomacy

Image Source : Google Maps

First Published in: Sep.08,2025

Sep.05, 2025

Introduction

The Arctic region, located above 66.5° N latitude and spanning approximately 14.5 million square kilometers, includes the Arctic Ocean, surrounding seas, and the northern territories of eight Arctic states -Canada, Denmark (via Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the United States.1 With melting ice opening critical maritime routes like the Northern Sea Route (NSR) and unlocking access to vital resources, global interest in the region has intensified. Governance remains limited to Arctic states within the Arctic Council, while non-Arctic countries like India hold observer status without voting rights.

India, despite its geographical distance, holds a strategic interest in the Arctic for scientific collaboration, climate research, and access to critical minerals. As a permanent observer since 2013, it has established the Himadri Research Station in Svalbard (78°55′N, 11°56′E) and the IndARC observatory in the Kongsfjorden fjord. Yet its influence is constrained by structural limitations and increasing competition from China, which actively seeks Arctic access through its Polar Silk Road. This paper argues that scientific diplomacy can serve as a key lever for India to deepen engagement, enhance its strategic presence, and align Arctic access with its broader energy and climate security goals.

Strategic Importance

The Arctic is no longer a distant, frozen periphery of global landmass, it has become a contention of resource politics, climate urgency and military escalation. Once defined by remoteness, the region today hosts an intensifying convergence of climate disruption, mineral access and geostrategic rivalry. As Arctic ice recedes at unprecedented rates, the region is unlocking new navigational routes and exposing valuable reserves of critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements and copper2 which are resources crucial to the global green energy transition.

Indian Involvement and Presence

India’s official interest in the Arctic began with its first expedition in 2007 and has since matured with the establishment of the Himadri research station (2008),3 IndARC Observatory (2014)4 and a series of bilateral research collaborations. India’s Arctic Policy, released in 2022, formalized its intent to participate in scientific, economic and environmental cooperation across six thematic pillars: research, environmental protection, resource exploration, logistics, governance and capacity building.

Despite these efforts, India’s observer status in the Arctic Council grants no voting rights and limited influence over policy formation. This structural limitation is exacerbated by the growing strategic assertiveness of China and Russia. Both nations have expanded dual-use infrastructure in the Arctic, including China’s self-declared “Near- Arctic State”5 status and Russia’s militarization of its northern flank. For India, this presents both challenges and opportunities.

The Arctic’s emerging importance intersects with India’s national priorities in vital areas, such as:

a) Securing climate-relevant data to understand and mitigate monsoon and GLOF (Glacial Lake Outburst Floods) patterns.

b) Accessing critical minerals for its 2070 net-zero emissions goal and green industrialization.6

Strategic Importance of the Arctic for India

The Arctic’s geo-environmental dynamics have profound consequences for India. The increased melting of the Greenland and Arctic ice sheets contributes to the rise in sea levels and fluctuations in monsoon variability through changing planetary wave patterns.7 The Himadri station in Ny-Alesund and IndArc mooring offer India unique insight into these processes, feeding long-range weather forecasting models via NCPOR-ISRO pipelines.

On the diplomatic front, as the only Global South climate observer, India’s data-sharing from Arctic observatories strengthens its credibility within forums such as the Arctic Council’s Environment Protection Working Group and the Sustaining Arctic Observing Networks (SAON).

Unlocking shipping corridors like NSR and CVMC could reduce Europe’s shipping time from Asia by approx. 40-50%, generating economic dividends. India’s Navy and Merchant Marine benefit from Arctic route familiarity, while India’s global positioning is enhanced through maritime cooperation. This demonstrates the importance of the Arctic for climate, economy and diplomacy. Navigating the shifting maritime architecture may redefine global trade through corridors like NSR and the Chennai-Vladivostok Maritime Corridor (CVMC).8

Indian Policy and Strategic Gaps

India’s Arctic engagement is still relatively nascent in terms of international literature but is growing in strategic significance. The most foundational contributions include policy reviews by India’s Ministry of Earth Sciences (2022), Arctic Council science reports and multilateral white papers by think tanks and scholars.

a) Scientific Infrastructure and Diplomacy – India’s Arctic science program, anchored by Himadri and IndARC, has contributed valuable data on atmospheric variability, Arctic monsoon linkages and glacial melting. According to Krishnan et al (2021)9 India’s participation in the Ny-Alesund Science Managers Committee has facilitated cross-national collaboration with Norway, Germany and the UK. The use of ISRO satellites to monitor climate interactions also reflects a techno-diplomatic layer of soft power.

b) Policy and Strategic Gaps – India’s 2022 Arctic Policy was a milestone, but scholars critique its technocratic tone and lack of geopolitical urgency. Verma (2023)10 notes that the policy’s six pillars are too operational and overlook the need for a dedicated strategic or security component. With rising militarization of the Arctic by Russia and China, and NATO’s increased surveillance operations, India risks being a passive observer if strategy remains science-focused only.

c) Moreover, India’s Arctic policy has yet to align with its Act East or Indo-Pacific strategies, thereby missing synergies in maritime infrastructure and regional partnerships Chaudhury (2025)11

d) Critical Minerals and Strategic Supply Chains – India’s net-zero targets by 2070 and the Green Hydrogen Mission depend on sustainable access to lithium, cobalt and REEs. However, nearly 90% of India’s lithium and cobalt are sourced via Chinese refineries (ICWA 2024).12 The Arctic, particularly Greenland, Canada and Russia holds untapped reserves. India’s MoUs with Chile and Australia represent important steps, but lack continuity in Arctic-focused supply diplomacy.

e) Rising Security Competition – Russia’s reactivation of Soviet-era bases, introduction of hypersonic missile systems and increasing joint exercises with China in Arctic waters have altered the balance of power. According to the CSIS (2023), this militarization, while defensive in tone, is designed to deter NATO and non-Arctic encroachments. China, on the other hand, has institutionalized its Arctic ambitions via the Polar Silk Road, icebreaker fleets and joint resource ventures with Russia. Since India lacks comparable Arctic military presence or deep water capacity, a militarized response is not deemed appropriate.13 Instead, turning to diplomacy offers a non-threatening influential strategy, especially among neutral Arctic actors like Norway and Iceland.

f) Moreover, India’s GLOF technology can be showcased in forums such as the Arctic Climate Change Forum and NATO’s emerging climate nodes, blending humanitarian outreach with scientific cooperation. This positions India as an active partner in Arctic climate resilience.

Mineral Diplomacy and Green-Energy Autonomy

India’s green energy ambitions hinge on reliable supplies of lithium, cobalt, nickel and rare-earth elements critical to battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) and renewable storage solutions. The 2023 National Critical Mineral Mission diagnoses India’s near total dependence on Chinese supply chains. To break this dependency, strategic focus has shifted to geologically stable Arctic reserves in Greenland, Canada and Siberia. However, access to these mineral reserves demands more than diplomatic prowess, it requires project level cooperation built on scientific triads. India-Greenland MoUs should exist to propose joint surveys for these minerals with the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources.14

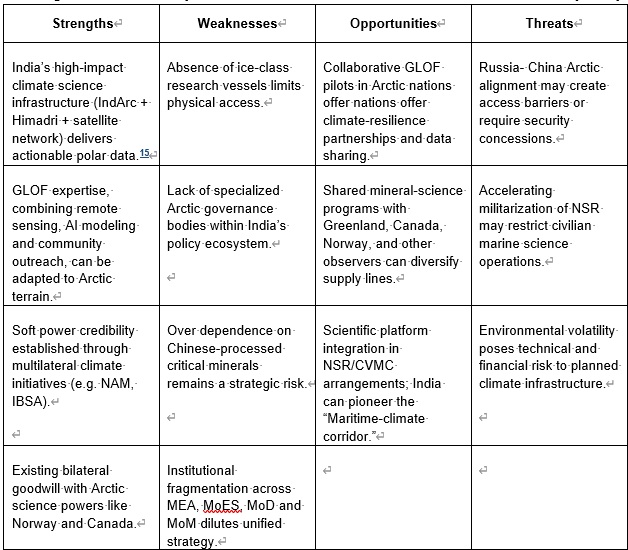

SWOT Analysis

An integrated SWOT analysis allows for a realistic assessment of India’s Arctic trajectory:

Recommendations

Based on the preceding analysis, the following recommendations integrate scientific diplomacy, climate technology and strategic logistics to boost India’s Arctic influence.

1. Establish an Indian Arctic-Earth Diplomacy Corps: Hosted jointly by the MEA and the MoES, IAEDC should comprise scientists, diplomats, oceanographers and military linguists specialized in Arctic affairs. They will lead institutional relations and field missions.

2. Expand Scientific Infrastructure: Upgrade Himadri Station into a multilateral research hub by inviting partner scientists and enabling joint projects. Additionally, post a mobile Arctic-Himalaya GLOF Expedition Team, designed by IIT Roorkee-NCPOR, 16 to Arctic communities for pilot data assimilation. India could also launch open-access Arctic climate data portal harmonized with ISRO satellites to promote transparency and scientific collaboration.

3. Launch the Green Minerals Research Alliance: With NITI Aayog approval, form an R&D network with Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and Norwegian or Canadian universities to explore joint technology solutions for sustainable mineral extraction.

4. Develop Maritime-Climate Corridors: Repurpose CVMC agreements to include climate-monitoring science hubs and shared logistics facilities across Arctic ports during summer navigation seasons.

5. Engage in Climate Security Exercises: Participate in or lead Arctic humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) exercises, deploying India’s unique Himalayan HADR expertise to Arctic conditions.

6. Strengthen institutional capacity: Add an Arctic Mandate Cell to NITI Aayog/DMEO for integrated policy planning across relevant ministries. Additionally, begin an Annual India-Arctic Science Summit, facilitating policy dialogue, mineral-science collaboration, sharing climate technology and youth and student fellowships based mostly on Arctic research and education.

Conclusion and Scope for Further Research

India’s Arctic observer status offers a unique but limited opening. By wielding scientific diplomacy as a central instrument, India can convert passive Arctic presence into strategic influence without seeking voting rights or military buildup.

The science-driven strategy empowers India to:

1. Conduct climate resilient modeling and synchronization for both Himalayan and Arctic regions.

2. Secure mineral access gradually through transparent and partner-driven resource diplomacy.

3. Enrich maritime connectivity via CVMC/NSR corridors supported by joint data sharing.

4. Preserve strategic autonomy while aligning climate and development objectives with global governance standards.

Through case studies of GLOF modeling, joint mineral exploration and maritime climate corridors, India can operationalize sustainable soft power influence. These initiatives reinforce India’s green ambitions and help disconnect critical and military-driven inputs from dominant actors like China.

Future research could examine legal frameworks underpinning India’s non-Arctic science based rights, economic evaluations of Indian-built ice class vessels and evaluation systems for policy success metrics in Arctic diplomacy.

Overall, by framing Arctic engagement as an extension of climate-resilient and demilitarized diplomacy, India emerges as a critical stakeholder in polar governance which is determined by climate science, research, data exchange, transparency as well as mutually beneficial diplomatic relations with Arctic council members and observer members.

References

1. Arctic Portal. “Arctic Circle.” Arctic Portal Maps. https://arcticportal.org/maps/download/arctic-definitions/2418-arctic-circle

2. Ollila, Mirkka Elisa. “The Triangle of Extraction in the Kola Peninsula.” The Arctic Institute, October 1, 2024. Accessed June 18, 2025. https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/triangle-extraction-kola-peninsula/

3. National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research. “Himadri Station.” NCPOR – Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India. Accessed June 18, 2025. https://ncpor.res.in/app/webroot/pages/view/340-himadri-station

4. National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research. “IndARC.” NCPOR – Ministry of Earth Sciences, Government of India. https://ncpor.res.in/arctics/display/398-indarc

5. Merkle, David. “The Self‑Proclaimed Near‑Arctic State.” International Reports (Auslandsinformationen),Konrad‑Adenauer‑Stiftung. https://www.kas.de/en/web/auslandsinformationen/artikel/detail/-/content/der‑selbsternannte‑fast‑arktisstaa

6. Ministry of Science & Technology, Government of India. “India Is Committed to Achieve the Net Zero Emissions Target by 2070 as Announced by PM Modi, Says Dr. Jitendra Singh.” Press Information Bureau, Government of India, September 28, 2023. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1961797

7. Association of American Universities. “Ice Sheet Surface Melt Is Accelerating in Greenland and Slowing in Antarctica.” Featured Research Topics, Association of American Universities, May 26, 2025. https://www.aau.edu/research-scholarship/featured-research-topics/ice-sheet-surface-melt-accelerating-greenland-and

8. Korea Centre (Mahatma Gandhi University). “The Arctic and Northern Sea Route: A New Frontier for India–South Korea Cooperation.” Korea Centre, April 7, 2025. https://koreacentre.org/2025/04/07/the-arctic-and-northern-sea-route-a-new-frontier-for-india-south-korea-cooperation/

9. Krishnan, K.P., and S. Venkatachalam. “Chapter 2 – India’s Scientific Endeavors in the Arctic with Special Reference to Climate Change: The Past Decade and Future Perspectives.” In Understanding Present and Past Arctic Environments: An Integrated Approach from Climate Change Perspectives, 15–29. 2021. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128228692000062

10. Kumar, Ashish, and Sudheer Singh Verma. “The Arctic Region: National Interests and Policies of India and China.” January 2023. PDF. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ashish-Kumar-591/publication/388222280_The_Arctic_Region_National_Interests_and_Policies of_India_and_China/links/678fca07ec3ae3435a733a47/The-Arctic-Region-National-Interests-and-Policies-of-India-and-China.pdf

11. Observatory of Regional Transformations (ORF). “From Look East to Act East: Mapping India’s Southeast Asia Engagement.” Observer Research Foundation, 2025. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://www.orfonline.org/research/from-look-east-to-act-east-mapping-india-s-southeast-asian-engagement

12. Indian Council of World Affairs. “From Look East to Act East: Mapping India’s Southeast Asia Engagement.” ICWA. https://www.icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=3&ls_id=10458&lid=6669

13. Osho, Zerin, and Eoin Jackson. “The Polar Tiger: Why India Must Be Included in the New U.S. Arctic Defense Strategy.” High North News, November 28, 2023. https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/polar-tiger-why-india-must-be-included-new-us-arctic-defense-strategy

14. Greenland Institute of Natural Resources. Frontpage. Nuuk, Greenland. https://natur.gl/

15. ThePrint, What Are Indian Researchers Doing in the Arctic Circle? YouTube video, 2:26, published https://youtu.be/WsZO0ZCTSyI?si=ysLbBnkAiqYzIlMp

16. Centre of Excellence in Disaster Mitigation & Management, Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee. Home. https://iitr.ac.in/Centres/Centre%20of%20Excellence%20in%20Disaster%20Mitigation%20and%20Management/Home.html

First published in :

World & New World Journal

Sneh Kotak is from Nairobi, Kenya, pursuing her MA in Politics and International Relations in India. Her academic interests focus on Asian and African studies, with particular emphasis on diplomacy, global governance, geopolitics and conflict resolution. She has published a bilingual poetry collection, Out of Maasai Land (2024), and has engaged in research exploring press freedom in comparative contexts. Her work reflects a broader interest in the intersections of media, politics, and international relations across economics, diplomacy and gender studies.

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!