Diplomacy

US Electoral System

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Diplomacy

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Dec.08,2025

Dec.08, 2025

I. Introduction

Elections in the United States are held for government officials at the federal, state, and local levels. At the federal level, the head of state, the President, is elected indirectly by the people of each state, through an Electoral College. All members of the federal legislature, the Congress, are directly elected by the people of each state. There are many elected offices at state level, each state having at least an elective governor and legislature. In addition, there are elected offices at the local level, in counties, cities, towns, and villages, as well as for special districts and school districts which may transcend county and municipal boundaries.

The US election system is highly decentralized. While the US Constitution sets parameters for the election of federal officials, state laws regulate most aspects of elections in the US, including primary elections, the eligibility of voters (beyond the basic constitutional definition), the method of choosing presidential electors, as well as the running of state elections. All elections-federal, state, and local-are administered by the individual states, with many aspects of the electoral system’s operations delegated to the county or local level. [1]

Under federal law, the general elections of the president and Congress are held in even-numbered years, with presidential elections occurring every four years, and congressional elections taking place every two years. The general elections that are held two years after the presidential ones are referred to as the mid-term elections. General elections for state and local offices are held at the discretion of the individual state and local governments, with many of these races coinciding with either presidential or mid-term elections as a matter of cost saving and convenience, while other state and local races may occur during odd-numbered “off years.” The date when primary elections for federal, state, and local races take place are also at the discretion of the individual state and local governments; presidential primaries in particular have historically been staggered between the states, beginning sometime in January or February, and ending about mid-June before the November general election. [2]

With this basic information in mind, this paper explores the US electoral system. This paper first provides an overview of the US electoral system and then explains the US Congress (Senate and House of Representatives) and features of US electoral systems. Finally, the paper compares the US electoral system with Canadian and Mexican electoral systems.

II. US Elections

1. Federal elections

The United States has a presidential system of government, which means that the executive and legislature are elected separately. Article II of the US Constitution requires that the election of the US president by the Electoral College must take place on a single day throughout the country; Article I established that elections for Congressional offices, however, can be held at different times. Congressional and presidential elections are held simultaneously every four years, and the intervening Congressional elections, which take place every two years, are called mid-term elections.

The US constitution states that members of the US House of Representatives must be at least 25 years old, a US citizen for at least seven years, and be a legal inhabitant of the state that they represent. Senators must be at least 30 years old, an US citizen for at least nine years, and be a (legal) inhabitant of the state that they represent. The president and vice president must be at least 35 years old, a natural born US citizen, and a resident in the US for at least 14 years. It is the responsibility of state legislatures to regulate the qualifications for a candidate appearing on a ballot paper, although in order to get onto the ballot, a candidate must often collect a legally defined number of signatures or meet other state-specific requirements. [3]

A. Presidential elections

Overview of the presidential election process

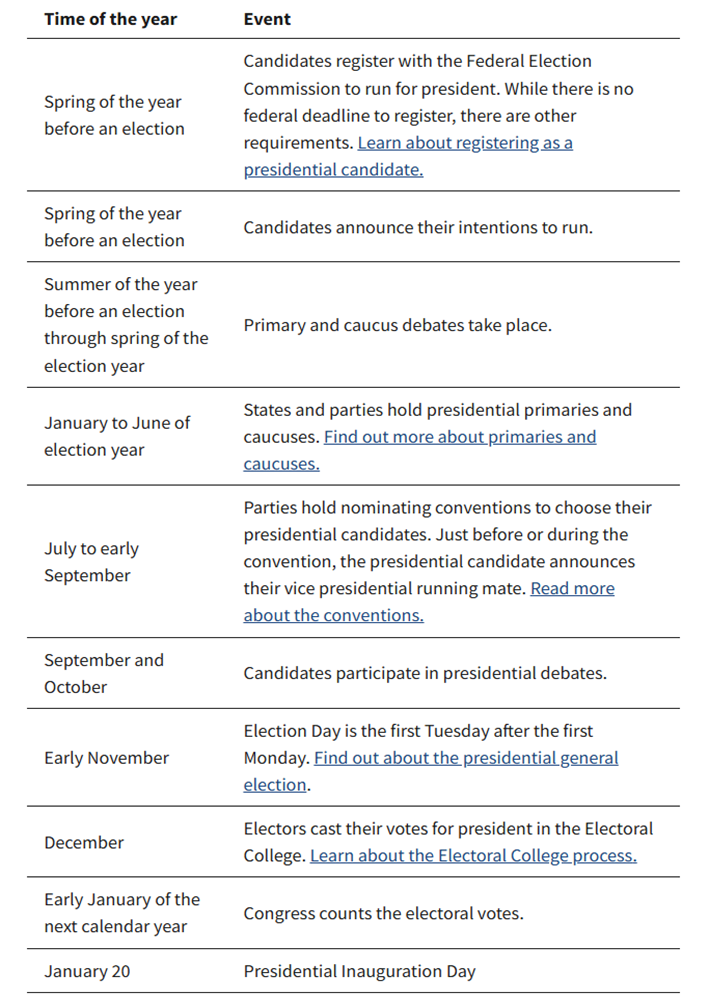

The presidential election process in the US follows a typical cycle as Table 1 shows.

Table 1: US Presidential Election Cycle

(source: USA In Brief: ELECTIONS. https://www.usa.gov/presidential-election-process)

The president and the vice president in the US are elected together in a presidential election. It is an indirect election, with the winner being determined by votes cast by electors of the Electoral College. The winner of the election is the candidate with at least 270 Electoral College votes. It is possible for a candidate to win the electoral vote, but lose the nationwide popular vote (receive fewer votes nationwide than the second ranked candidate). This has happened five times in US history: in 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016. [4]

Electoral College votes are cast by individual states by a group of electors; each elector casts one electoral college vote. Until the Twenty-third Amendment to the US Constitution in 1961, citizens from the District of Columbia did not have representation in the electoral college.

State laws regulate how states cast their electoral college votes. In all states except Nebraska and Maine, the candidate that wins the most votes in the state receives all its electoral college votes (a “winner takes all” system). From 1996 in Nebraska, and from 1972 in Maine, two electoral votes are awarded based on the winner of the statewide election, and the rest (three in Nebraska and two in Maine) go to the highest vote-winner in each of the state’s congressional districts. [5]

The Electoral College

Overview of the Electoral College

In the US, the Electoral College is the group of presidential electors that is formed every four years for the sole purpose of voting for the president and vice president in the presidential election. This process is explained in Article Two of the US Constitution. The number of electors from each state is equal to that state’s congressional delegation which is the number of senators (two) plus the number of Representatives for that state. Each state appoints electors using legal procedures determined by its legislature. Federal office holders, including US senators and representatives, cannot be electors. In addition, the Twenty-third Amendment granted the federal District of Columbia three electors (bringing the total number from 535 to 538). A simple majority of electoral votes (270 or more) is required to elect the president and vice president. If no candidate receives a majority, a contingent election is held by the House of Representatives, to elect the president, and by the Senate, to elect the vice president. [6]

The states and the District of Columbia hold a statewide or district-wide popular vote on Election Day in November to choose electors based upon how they have pledged to vote for president and vice president, with some state laws prohibiting faithless electors. All states except Nebraska and Maine use a party block voting, or general ticket method, to choose their electors, meaning all their electors go to one winning ticket. Nebraska and Maine choose one elector per congressional district and two electors for the ticket with the highest statewide vote. The electors meet and vote in December, and the inaugurations of the president and vice president take place in next January.

The merit of the electoral college system has been a matter of ongoing debate in the US since its inception at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, becoming more controversial by the latter years of the 19th century, up to the present day. More resolutions have been submitted to amend the Electoral College mechanism than any other part of the US constitution. An amendment that would have abolished the system was approved by the House in 1969, but failed to move past the Senate. [7]

Supporters of the Electoral College claim that it requires presidential candidates to have broad appeal across the country to win, while critics argue that it is not representative of the popular will of the nation.

Procedure of Electoral College

Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 of the US Constitution directs each state to appoint a number of electors equal to that state’s congressional delegation (two senators plus the number of members of the House of Representatives). The same clause empowers each state legislature to determine the manner by which that state’s electors are chosen but prohibits federal office holders from becoming electors. Following the national presidential election day on Tuesday after the first Monday in November, each state, and the federal district, selects its electors according to its laws. [8] After a popular election, the states identify and record their appointed electors in a Certificate of Ascertainment, and those appointed electors then meet in their respective jurisdictions and produce a Certificate of Vote for their candidate; both certificates are then sent to US Congress to be opened and counted. [9]

In 48 of the 50 states, state laws mandate that the winner of the plurality of the statewide popular vote receives all of that state’s electoral votes. In Nebraska and Maine, two electoral votes are assigned in this manner, while the remaining electoral votes are allocated based on the plurality of votes in each of their congressional districts. The federal district (Washington, D.C.) allocates its 3 electoral votes to the winner of its single district election. States generally require electors to pledge to vote for that state’s winning ticket; to prevent electors from being faithless electors, most states have adopted various laws to enforce the electors’ pledge. [10]

The electors of each state meet in their respective state capital on the first Tuesday after the second Wednesday of December, between December 14 and 20, to cast their votes. The results are sent to and counted by the Congress, where they are tabulated in the first week of January before a joint meeting of the Senate and the House of Representatives, presided over by the current vice president, who is the president of the Senate. [11]

Should a majority of votes not be cast for a candidate, a contingent election takes place: the House of Representatives holds a presidential election session, where one vote is cast by each of the fifty states. The Senate is responsible for electing the vice president, with each senator having one vote. The elected president and vice president are inaugurated on January 20.

Since 1964, there have been 538 electors. States select 535 of the electors, this number matches the aggregate total of their congressional delegations. [12] The additional three electors came from the Twenty-third Amendment, ratified in 1961, providing that the district established pursuant to Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 as the seat of the federal government (namely, Washington, D.C.) is entitled to the same number of electors as the least populous state. In practice, that results in Washington D.C. being entitled to three electors. [13]

Figure 1: Current number of presidential electors by state in US (Source: Wikipedia)

B. Congressional elections

Overview of US Congress

The US Congress is the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a bicameral legislature, including a lower body, the US House of Representatives, and an upper body, the US Senate. They both meet in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.

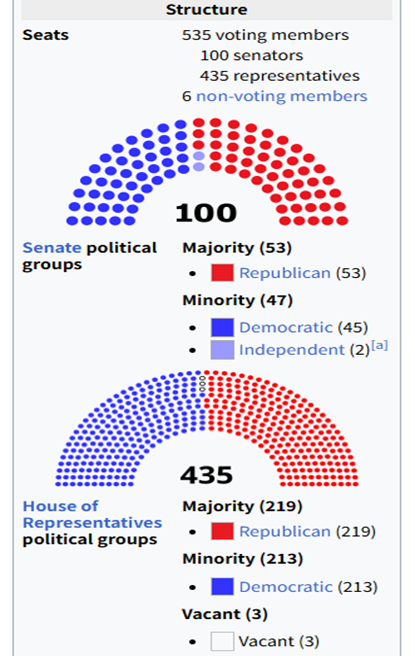

Members of Congress are chosen through direct election, though vacancies in the Senate may be filled by a governor’s appointment. As Figure 2 shows, Congress has a total of 535 voting members, a figure which includes 100 senators and 435 representatives. The vice president of the United States, as president of the Senate, has a vote in the Senate only when there is a tie. [14]

Figure 2: Current US Congress Structure (Source: Wikipedia)

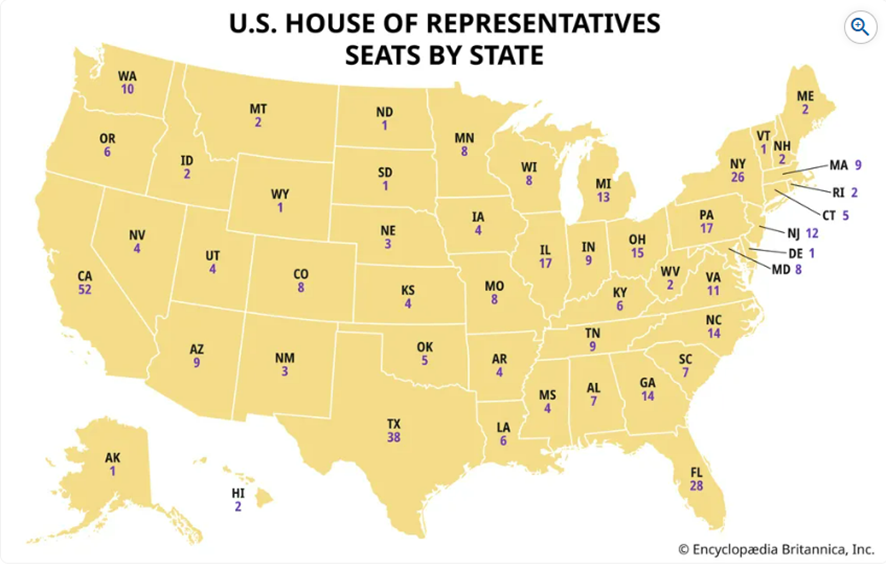

Congress convenes for a two-year term (a Congress), commencing every other January. Each Congress is usually split into two sessions, one for each year. Elections are held every even-numbered year on Election Day. The members of the House of Representatives are elected for the two-year term of a Congress. The Reapportionment Act of 1929 established that there be 435 representatives, and the Uniform Congressional District Act requires that they be elected from single-member constituencies or districts. It is also required that the congressional districts be apportioned among states by population every ten years using the US census results, provided that each state has at least one congressional representative. Each senator is elected at-large in their state for a six-year term, with terms staggered, so every two years approximately one-third of the Senate is up for election. Each state, regardless of size and population, has two senators, so currently, there are 100 US senators for the 50 states. [15]

Article One of the US Constitution requires that members of Congress be at least 25 years old for the House and at least 30 years old for the Senate, be a US citizen for seven years for the House and nine years for the Senate, and be an inhabitant of the state that they represent. Members in both chambers may run for re-election an unlimited number of times. [16]

Figure 3: US House of Representatives Seats by State (source: Britannica)

Congress was created by the US Constitution and first met in 1789, replacing the Congress of the Confederation in its legislative function. Although not legally mandated, in practice members of Congress since the late 19th century are typically affiliated with one of the two major political parties, the Democratic Party or the Republican Party, and only rarely with a third party or independents affiliated with no party. Members of Congress can also switch parties at any time, though this is uncommon. [17]

Role & Power of US Congress

Article One of the US Constitution states that “All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a US Congress, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives.” [18] The House and Senate are equal partners in the legislative process – legislation cannot be enacted without the consent of both chambers. The US Constitution grants each chamber some unique powers. The Senate ratifies treaties and approves presidential appointments while the House initiates revenue-raising bills.

The House initiates and decides impeachment while the Senate votes on conviction and removal of office for impeachment cases. A two-thirds vote of the Senate is required before an impeached person is removed from office. [19]

US Congress has authority over budgetary and financial policy through the enumerated power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States.

The Sixteenth Amendment in 1913 extended congressional power of taxation to include income taxes without apportionment among the several states, and without regard to any census or enumeration. The US Constitution also grants Congress the exclusive power to appropriate funds, and this power of the purse is one of Congress’s primary checks on the executive branch of the United States. Congress can borrow money on the credit of the US, regulate commerce with foreign nations and among the states, and coin money. Generally, the Senate and the House of Representatives have equal legislative authority, although only the House may originate revenue and appropriation bills. [20]

In addition, Congress has an important role in national defense, including the exclusive power to declare war, to raise and maintain the armed forces, and to make rules for the military. Some critics charge that the executive branch has usurped Congress’s constitutionally defined task of declaring war. While historically presidents initiated the process for going to war, they asked for and received formal war declarations from Congress for the War of 1812, the Spanish–American War, the Mexican–American War, World War I, and World War II, although President Theodore Roosevelt’s military move into Panama in 1903 did not get congressional approval. In 1993, Michael Kinsley wrote that “Congress’s war power has become the most flagrantly disregarded provision in the Constitution,” and that the “real erosion of Congress’s war power started after World War II.” Disagreement about the extent of congressional versus presidential power regarding war has been present from time to time throughout US history. [21]

US Congress can establish post offices and post roads, issue patents and copyrights, fix standards of weights and measures, establish courts inferior to the US supreme court, and make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the US, or in any Department or officer thereof. Article Four gives US Congress the power to admit new states into the Union.

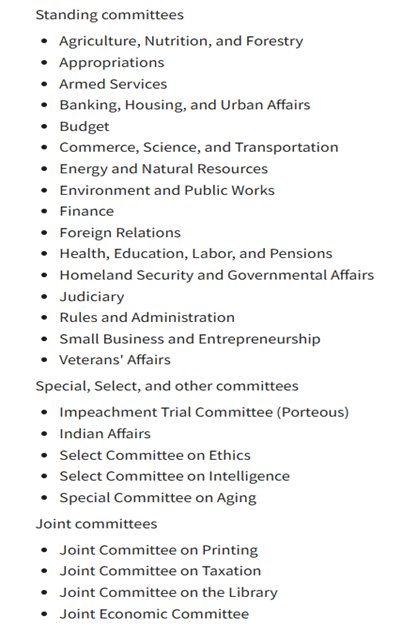

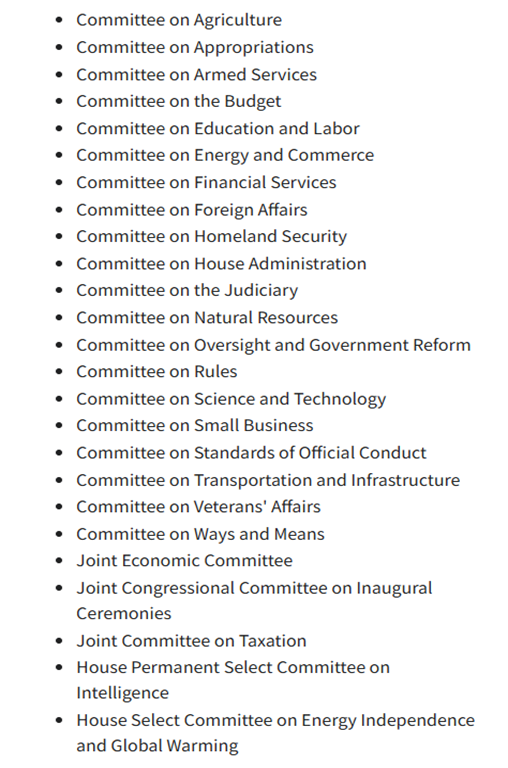

One of Congress’s foremost non-legislative functions is the power to investigate and oversee the executive branch. Congressional oversight is usually delegated to committees and is facilitated by Congress’s subpoena power (see Tables 2 & 3). Some critics have charged that the US Congress has in some instances failed to do an adequate job of overseeing the other branches of government. In the Plame affair, critics including US Representative Henry A. Waxman charged that Congress was not doing an adequate job of oversight in this case. [22]

Table 2: Major Senate committees (source: Wikipedia)

Table 3: Major House committees (source: Wikipedia)

Power of US Senate

Senate approval is required to pass any federal legislation. The US Constitution provides several unique functions for the Senate that form its ability to “checks and balances” the powers of other elements of the federal government. These include the requirement that the Senate may advise and must consent to some of the president’s government appointments; the Senate must also consent to all treaties with foreign governments; it tries all impeachments, and it elects the vice president in the event no person receives a majority of the electoral votes.

Legislation

Bills may be introduced in either chamber of Congress. However, the Constitution’s Origination Clause provides that All bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives. [23] Accordingly, the Senate does not have the power to initiate bills imposing taxes. Moreover, the House of Representatives holds that the Senate does not have the power to originate appropriation bills, or bills authorizing the expenditure of federal funds. The constitutional provision barring the Senate from introducing revenue bills is based on the practice of the British Parliament, in which money bills approved by Parliament have originated in the House of Commons per constitutional convention.

Although the US Constitution gave the House the power to initiate revenue bills, in practice the Senate is equal to the House in the respect of spending. As Woodrow Wilson wrote: [24]

The Senate’s right to amend general appropriation bills has been allowed the widest possible scope. The Senate may add to them what it pleases; may go altogether outside of their original provisions and tack to them entirely new features of legislation, altering not only the amounts but also even the objects of expenditure, and making out of the materials sent them by the popular chamber measures of an almost totally new character.

The approval of both chambers is required for any bill, including a revenue bill, to become law. Both the House and the Senate must pass the same version of the bill; if there are differences, they may be resolved by sending amendments back and forth or by a conference committee that includes members of both bodies.

Appointment confirmations

The president can make certain appointments only with the advice and consent of the Senate. Officials whose appointments require the Senate’s approval include members of the Cabinet, ambassadors, heads of most federal executive agencies, justices of the Supreme Court, and other federal judges.

The powers of the Senate concerning nominations are, however, subject to some constraints. For instance, the US Constitution provides that the president may make an appointment without the Senate’s advice and consent during a congressional recess. The recess appointment remains valid only temporarily; the office becomes vacant again at the end of the next congressional session. Nonetheless, presidents have frequently used recess appointments to circumvent the possibility that the Senate may reject the nominee. Moreover, as the Supreme Court held in Myers v. United States, although the Senate’s advice and consent are required for the appointment of certain executive branch officials, it is not necessary for their removal. However, recess appointments have faced a significant amount of resistance and in 1960, the US Senate passed a legally non-binding resolution against recess appointments to the Supreme Court. [25]

Treaty ratification

Moreover, the Senate has a role in ratifying treaties. The US Constitution provides that the president may only “make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the senators present concur” in order to benefit from the Senate’s advice and consent and give each state an equal vote in the process. However, not all international agreements are considered treaties under US domestic law, even if the agreements are considered treaties under international law. Congress has passed laws authorizing the president to conclude executive agreements without action by the Senate. In a similar way, the president may make congressional-executive agreements with the approval of a simple majority in each House of Congress, rather than a two-thirds majority in the Senate. Neither executive agreements nor congressional-executive agreements are mentioned in the Constitution, leading some scholars such as John Yoo and Laurence Tribe to suggest that they unconstitutionally circumvent the treaty-ratification process. However, US courts have upheld the validity of such agreements. [26]

Impeachment trials

The US Constitution empowers the House of Representatives to impeach federal officials for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors” and empowers the Senate to try such impeachments. If the sitting president of the United States is being tried, the US chief justice presides over the trial. During an impeachment trial, senators are constitutionally required to sit on oath or affirmation. Conviction requires a two-thirds majority of the senators present. A convicted official is automatically removed from office. In addition, the Senate may stipulate that the defendant is banned from holding office. No further punishment is permitted during the impeachment proceedings; however, the party may face criminal penalties in a normal court of law.

The House of Representatives has impeached sixteen government officials, of whom seven were convicted (one resigned before the Senate could complete the trial). Only three US presidents have been impeached: Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1998, and Donald Trump in 2019 and 2021. The trials of Johnson, Clinton and both Trump trials ended in acquittal; in Johnson’s case, the Senate fell one vote short of the two-thirds majority required for conviction. [27]

Election of the vice president

Under the Twelfth Amendment, the Senate has the power to elect the vice president if a vice-presidential candidate does not receive a majority of votes in the Electoral College. The Twelfth Amendment requires the Senate to choose from the two candidates with the highest numbers of electoral votes. But Electoral College deadlocks are rare. The Senate has only broken a deadlock once; in 1837, it elected Richard Mentor Johnson. The House elects the president if the Electoral College deadlocks on that choice. [28]

Power of US House of Representatives

The US House of Representatives has the exclusive power to initiate all revenue bills, impeach federal officials, and elect the US president if the Electoral College is tied. Along with the Senate, it also shares the power to make laws. [29]

The organization and character of the House of Representatives have evolved under the influence of political parties, which provide a means of controlling proceedings and mobilizing the necessary majorities. Party leaders, such as the majority and minority leaders, as well as the speaker of the House, play a central role in the operations of the House. However, party discipline (for example, the tendency of all members of a political party to vote in the same way) has not always been strong due to the fact that House members, who must face reelection every two years, often vote the interests of their districts rather than their political party when the two diverge.

A further dominating element of House organization is the committee system, under which the membership is divided into specialized groups for purposes such as preparing bills for the consideration of the entire House, regulating House procedure, and holding hearings. Each committee is chaired by a member of the majority party. Almost all bills are first referred to a committee, and ordinarily the full House cannot act on a bill until the committee has “reported” it for floor action. There are approximately 20 standing committees, organized mainly around major policy areas, each having subcommittees, staffs, and budgets. They may hold hearings on questions of public interest, propose legislation that has not been formally introduced as a bill or resolution, and conduct investigations. Among important standing committees are those on appropriations, on ways and means (which handles matters related to finance), and on rules. In addition, there are select and special committees, which are usually appointed for a specific project and for a limited period of time.

The committees also play an important role in the control exercised by Congress over governmental agencies. Cabinet officers and other officials are frequently summoned before the committees to explain policy. The US Constitution (Article I, section 6) prohibits members of Congress from holding offices in the executive branch of government—a major difference between parliamentary and congressional forms of government. [30]

2. State elections

Overview

State laws and state constitutions, controlled by state legislatures regulate elections at state level and local level. Various officials at the state level are elected. Since the separation of powers applies to states as well as the federal government, state legislatures and the executive (for example, the governor) are elected separately. Governors and lieutenant governors are elected in all states, in some states on a joint ticket and in some states separately, some separately in different electoral cycles. The governors of the territories of American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the US Virgin Islands are also elected. In some states, executive positions such as Secretary of State and Attorney General are also elected offices. All members of state legislatures and territorial jurisdiction legislatures are elected. In some states, members of the state supreme court and other members of the state judiciary are elected. Proposals to amend the state constitution are also placed on the ballot in some states. [31]

As a matter of cost saving and convenience, elections for many of these state and local offices are held at the same time as either the federal presidential or mid-term elections. There are a handful of states, however, that hold their elections during odd-numbered “off years.”

Governors

As state managers, governors are mainly responsible for implementing state laws and overseeing the operation of the state executive branch. As state leaders, governors advance and pursue new and revised programs and policies using a variety of tools, among them executive orders, executive budgets, and legislative proposals and vetoes. As chiefs of the state, governors serve as the intergovernmental liaison to the federal government on behalf of the state. [32]

Governors carry out their management and leadership responsibilities and objectives with the support and assistance of agency & department heads, many of whom they are empowered to appoint. A majority of governors have the power to appoint state court judges as well, in most cases from a list of names submitted by a nominations committee.

Although governors have many roles and responsibilities in common, the scope of gubernatorial power varies from state to state in accordance with state constitutions, legislation, and tradition. Governors often are ranked by political historians and other observers of state politics according to the extent and number of their powers.

States, commonwealths, or territories vary with respect to minimum age, US citizenship, and state residency requirements for gubernatorial candidates and other state office holders. The minimum age requirement for governors ranges from no formal provision to age 35. The requirement of US citizenship for gubernatorial candidates ranges from no formal provision to 20 years. State residency requirements range from no formal provision to 7 years. [33]

State legislature

In the United States, the state legislature is the legislative branch in each of the 50 US states.

A legislature generally performs state duties for a state in the same way that the US Congress performs national duties at the national level. Generally, the same system of checks and balances at the federal level also exists between the state legislature, the state executive officer (governor) and the state judiciary.

In 27 states, the legislature is called the legislature or state legislature. In other 19 states, the legislature is called the general assembly. In New Hampshire and Massachusetts, the legislature is called the general court, while North Dakota and Oregon designate the legislature the legislative assembly. [34]

The responsibilities of a state legislature vary from state to state, depending on the state’s constitution.

The primary function of any legislature is to make laws. State legislatures also approve budgets for state government. They may establish government agencies, set their policies, and approve their budgets. For example, a state legislature could establish an agency to manage environmental conservation efforts within that state. In some states, state legislators elect other state officials.

State legislatures often have the power to regulate businesses operating within their jurisdiction. They also regulate courts within their jurisdiction. This includes determining types of cases that can be heard, regulating attorney conduct, and setting court fees.

With respect to other responsibilities of a state legislature, under the terms of Article V of the US Constitution, state lawmakers have the power to ratify Constitutional amendments which have been proposed by both houses of Congress and they also retain the ability to call for a national convention to propose amendments to the US Constitution. [35]

After the convention has concluded its business, 75% of the states will ratify what the convention has proposed. Under Article II, state legislatures choose the manner of appointing the state’s presidential electors. In the past, some state legislatures appointed the US Senators from their respective states until the ratification of the 17th Amendment in 1913 required the direct election of senators by the state’s voters.

Sometimes what the legislature wishes to achieve cannot be done simply by the passage of a bill, but rather requires amending the state constitution. Each state has specified steps intended to make it difficult to revise the constitution without the sufficient support of either the legislature, or the people, or both.

Organization

All states except Nebraska have a bicameral legislature. The smaller chamber is called the senate, usually referred to as the upper house. This chamber usually has the exclusive power to confirm appointments made by the governor and to try articles of impeachment. (In a few states, a separate executive council, composed of members elected from large districts, performs the confirmation procedures.)

Nebraska originally had a bicameral legislature like other states, but the lower house was abolished following a referendum, effective with the 1936 elections. The remaining unicameral (one-chamber) legislature is called the Nebraska Legislature, but its members are called state senators.

During the 20th century, state legislatures further emulated the activities and structures of the US Congress as institutions at both levels grew in size and complexity, often accompanied by increases in staffing and member pay. While most state legislatures remain part-time institutions, a handful of states have expanded theirs to meet year-round. [36]

Local elections

At the local level, county and city government positions are usually filled by election, in particular within the legislative branch. The extent to which offices in the executive or judicial branches are elected vary from city-to-city or county-to-county. Some examples of local elected positions include sheriffs at the county level and mayors and school board members at the city level. Like state elections, an election for a specific local office may take place at the same time as either the presidential, mid-term, or off-year elections.

III. Features of US electoral system

Voting methods

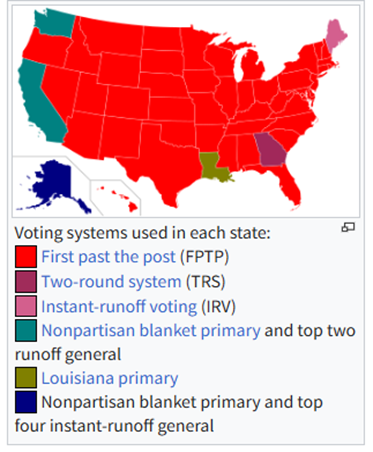

A number of voting methods are used within the various jurisdictions in the US, the most common of which is the first-past-the-post system. In the first-past-the-post system, the highest-polling candidate wins the election. Under this system, a candidate who achieves a plurality (that is, the most) of votes wins. But the State of Georgia uses a two-round system, where if no candidate receives a majority of votes, then there is a runoff between the two highest polling candidates. [37]

Since 2002, several cities such as Burlington in Vermont have adopted instant-runoff voting. Voters rank the candidates in order of preference rather than voting for a single candidate. Under this system, if no candidate receives more than half of votes cast, then the lowest polling candidate is eliminated, and their votes are distributed to the next preferred candidates. This process continues until one candidate receives more than half the votes. In 2016, Maine became the first state to adopt instant-runoff voting (known as ranked-choice voting) statewide for its elections, although due to state constitutional provisions, the system is only used for federal elections and state primaries. [38]

Figure 4: US voting methods (source: Wikipedia)

Eligibility

The eligibility of an individual for voting is set out in the US constitution and also regulated at state level. The constitution states that suffrage cannot be denied on grounds of color, race, sex, or age for citizens eighteen years or older. Beyond these basic qualifications, it is the responsibility of state legislatures to regulate voter eligibility. Some states ban convicted criminals, especially felons, from voting for a fixed period of time or indefinitely. The number of adults in the US who are currently or permanently ineligible to vote due to felony convictions is estimated to be 5.3 million. In addition, some states have legacy constitutional statements barring those legally declared incompetent from voting; such references are generally considered obsolete and are being considered for review or removal where they appear. [39]

About 4.3 million US citizens that reside in Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico and other US territories do not have the same level of federal representation as those that live in the 50 US states. These areas only have non-voting members in the US House of Representatives and no representation in the US Senate. Citizens in the US territories are also not represented in the Electoral College and therefore cannot vote for the US President. [40] Those in Washington, D.C. are allowed to vote for the president because of the Twenty-third Amendment.

Voter registration

While the federal government has jurisdiction over federal elections, most election laws are decided at the state level. All US states except North Dakota require that citizens who wish to vote be registered. In many states, voter registration takes place at the county or municipal level. Traditionally, voters had to register directly at state or local offices to vote, but in the mid-1990s, the federal government made a lot of efforts to make registering easier, in an attempt to increase turnout. The National Voter Registration Act of 1993 (the “Motor Voter” law) required state governments that receive certain types of federal funding to make the voter registration process easier by providing uniform registration services through drivers’ license registration centers, disability centers, libraries, schools, and mail-in registration. Other states allow citizens same-day registration on election day.

An estimated 50 million Americans are unregistered. It has been reported that registering to vote poses greater obstacles for low-income citizens, Native Americans, racial minorities and linguistic minorities, and persons with disabilities. International election observers have called on US authorities to implement measures to correct the problems of the high number of unregistered citizens. [41]

In many states, citizens registering to vote may declare an affiliation with a political party. This declaration of affiliation does not cost money, and does not make the citizen a dues-paying member of a party. A political party cannot prevent a voter from declaring his or her affiliation with the party, but it can refuse requests for full membership. In some states, only voters affiliated with a political party may vote in that party’s primary elections. Declaring a party affiliation is never required. Some states, including Georgia, Virginia, Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, and Washington, practice non-partisan registration. [42]

Non-citizen voting

Federal law prohibits non-citizens from voting in federal elections. As of 2024, 7 state constitutions specifically state that “only” a citizen can vote in elections at any level in that state: Florida, Alabama, Arizona, North Dakota, Colorado, Louisiana, and Ohio. [43]

Absentee and mail voting

Voters unable or unwilling to vote at polling stations on election day may vote via absentee ballots, depending on state law. Originally these ballots were for people who could not go to the polling place on the election day. Now some states let them be used for convenience, but state laws still call them absentee ballots. Absentee ballots can be sent and returned by mail, or requested and submitted in person, or dropped off in locked boxes. About half the states and territories allow “no excuse absentee,” where no reason is required to request an absentee ballot; other states require a valid reason, such as travel or infirmity. Some states let voters with permanent disabilities apply for permanent absentee voter status, and some other states let all citizens apply for permanent status, so they will automatically receive an absentee ballot for each election. Otherwise a voter must request an absentee ballot before the election takes place. [44]

In Colorado, Utah, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington state, all ballots are delivered through the mail; in many other states there are counties or certain small elections where everyone votes by mail. [45]

As of July 2020, 26 states allow designated agents to collect and submit ballots on behalf of another voter, whose identities are specified on a signed application. Such agents are usually family members or persons from the same residence. 13 states neither enable nor prohibit ballot collection as a matter of law. Among those that allow it, 12 states have limits on how many ballots an agent may collect.

Americans living outside the US, including active duty members of the armed forces stationed outside of their state of residency, may register and vote under the Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act (UOCAVA). Almost half the states require these ballots to be returned by mail. Other states allow mail along with some combination of e-mail or fax; four states allow a web portal. [46]

A significant measure to prevent some types of fraud has been to require the voter’s signature on the outer envelope, which is compared to one or more signatures on file before taking the ballot out of the envelope and counting it. Not all states have standards for signature review. There have been concerns that signatures are improperly rejected from young and minority voters at higher rates than others, with no or limited ability of voters to appeal the rejection. For other types of errors, experts estimate that while there is more fraud with absentee ballots than in-person voting, absentee ballots have affected only a few local elections. [47]

Following the US presidential election in 2020, amid disputes of its outcome, as a rationale behind litigation demanding a halt to official vote counting in some areas, allegations were made that vote counting is offshored. Former Trump Administration official Chris Krebs, head of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) during the election, said in a December 2020 interview that, “All votes in the United States of America are counted in the United States of America.” [48]

One documented trend is that in-person votes and early votes are more likely to lean to the Republican Party, while the provisional ballots, which are counted later, trend to the Democratic Party. This phenomenon is known as blue shift, and has led to situations where Republicans were winning on the election night only to be overtaken by Democrats after all votes were counted. But Foley did not find that mail-in or absentee votes favored either party. [49]

Early voting

Early voting is a formal process where voters can cast their ballots before the official election day. Early voting in person is allowed in 47 states and in Washington, D.C., with no excuse required. Only Alabama, New Hampshire and Oregon do not allow early voting, while some counties in Idaho do not allow it. [50]

Voting equipment

The earliest voting in the US was through paper ballots that were hand-counted. By the late 1800s, paper ballots printed by election officials were nearly universal. By 1980, 10% of American voters used paper ballots that were counted by hand, and then dropped below 1% by 2008. [51]

Mechanical voting machines were first used in the US in the 1892 elections in Lockport, New York. Massachusetts was one of the first states to adopt lever voting machines, doing so in 1899, but the state’s Supreme Court ruled their usage unconstitutional in 1907. Lever machines grew in popularity despite controversies, with about two-thirds of votes for president in the 1964 US presidential election cast with lever machines. Lever machine use declined to about 40% of votes in 1980, then 6% in 2008. Punch card voting equipment was developed in the 1960s, with about one-third of votes cast with punch cards in 1980. New York was the last state to phase out lever voting in response to the 2000 Help America Vote Act (HAVA) that allocated funds for the replacement of lever machine and punch card voting equipment. New York replaced its lever voting with optical scanning in 2010.

In the 1960s, technology was developed that enabled paper ballots filled with pencil or ink to be optically scanned rather than hand-counted. In 1980, about 2% of votes used optical scanning; this increased to 30% by 2000 and then 60% by 2008. In the 1970s, the final major voting technology for the US was developed, the DRE voting machine. In 1980, less than 1% of ballots were cast with DRE machines. Prevalence grew to 10% in 2000, and then peaked at 38% in 2006. Because DREs are fully digital, with no paper trail of votes, backlash against them caused prevalence to drop to 33% in 2010. [52]

The voting equipment used by a given US county is related to the county's historical wealth. A county’s use of punch cards in the year 2000 was positively correlated with the county’s wealth in 1969, when punch card machines were at their peak of popularity. Counties with higher wealth in 1989 were less likely to use punch cards in 2000. This supports the idea that punch cards were used in counties that were well-off in the 1960s, but whose wealth declined in the proceeding decades. Counties that maintained their wealth from the 1960s onwards could afford to replace punch card machines as they fell out of favor. [53]

Multiple levels of regulation

Elections in the US are actually conducted by local authorities, working under local, state, and federal law and regulation, as well as the US Constitution. It is a highly decentralized system.

The secretary of state in about half of US states is the official in charge of elections; in other states it is someone appointed for the job, or a commission. It is this person or commission who is responsible for certifying, tabulating, and reporting votes for the state.

Ballot access

Ballot access refers to the laws which regulate under what conditions access is granted for a candidate or political party to appear on voters’ ballots. Each state has its own ballot access laws to determine who may appear on ballots and who may not. According to Article I, Section 4, of the US Constitution, the authority to regulate the place, time, and manner of federal elections is up to each state, unless Congress legislates otherwise. Depending on the office and the state, it may be possible for a voter to cast a write-in vote for a candidate whose name does not appear on the ballot, but it is extremely rare for such a candidate to win office. [54]

Primaries and caucuses

In partisan elections, candidates are chosen by primary elections and caucuses in the states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, and the US Virgin Islands. [55]

A primary election is an election in which registered voters in a jurisdiction (nominating primary) select a political party’s candidate for a later election. There are various types of primary: either the whole electorate is eligible, and voters choose one political party’s primary at the polling booth (an open primary); or only independent voters can choose a party’s primary at the polling booth (a semi-closed primary); or only registered members of the political party are allowed to vote (closed primary). The blanket primary, when voters could vote for all parties’ primaries on the same ballot was struck down by the US Supreme Court as violating the First Amendment guarantee of freedom of assembly in the case California Democratic Party v. Jones. In addition, primaries are used to select candidates at the state level, for example, in gubernatorial elections.

Caucuses also nominate candidates by election, but they are very different from primaries. Caucuses are meetings that occur at precincts and involve discussion of each political party’s platform and issues such as voter turnout in addition to voting. Eleven states: Alaska, Colorado, Hawaii, Kansas, Iowa, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Wyoming, and the District of Columbia use caucuses, for one or more political parties. [56]

The primary and caucus season in presidential elections lasts from the Iowa caucus in January to the last primaries in June. Front-loading – when larger numbers of contests take place in the opening weeks of the season—can have an impact on the nomination process, potentially reducing the number of realistic candidates, as fund-raisers and donors quickly abandon those who they see as untenable. However, it is not the case that the successful candidate is always the candidate who does the best in the early primaries. There is also a period dubbed the “invisible primary” that takes place before the primary season, when candidates attempt to solicit media coverage and funding well before the real primary season begins.

A state’s presidential primary election or caucus usually is an indirect election: instead of voters directly selecting a particular person running for president, it determines how many delegates each party’s national political convention will receive from their respective state. These delegates then in turn select their party’s presidential nominee. Held in the summer, a political convention’s purpose is also to adopt a statement of the political party’s principles and goals known as the platform and adopt the rules for the party’s activities. [57]

The day on which primaries are held for congressional seats, and state and local offices may also vary from state to state. The only federally mandated day for elections is the election day for the general elections of the president and Congress; all other elections are at the discretion of the individual state and local governments.

Criticism and concerns

A. Voter suppression and subversion

Voting laws and procedures between the states vary as a consequence of the decentralized system, including those pertaining to voter IDs, voter registration, provisional ballots, postal voting, voting machines and vote counting, felony disenfranchisement, and election recounts. Thus the voting rights or voter suppression in one state may be stricter or more lenient than another state. After the 2020 US presidential election, decentralized administration and inconsistent state voting laws and processes have shown themselves to be targets for voter subversion schemes enabled by appointing politically motivated actors to election administration roles with degrees of freedom to subvert the will of the people. One such scheme would allow these election officials to appoint a slate of “alternate electors” to skew operations of the electoral college in favor of a minority political party. [58]

B. Vote counting time

As detailed in a state-by-state breakdown, the US has a long-standing tradition of publicly announcing the incomplete, unofficial vote counts on election night (the late evening of election day), and declaring unofficial “projected winners,” despite that many of the mail-in and absentee votes have not been counted yet. In some states, in fact, none of them have yet been counted by that time. This tradition was based on the assumption that the incomplete, unofficial count on the election night is probably going to match the official count, which is officially finished and certified several weeks later. A basic weakness of this assumption, and of the tradition of premature announcements based on it, is that the general public is likely to misapprehend that these particular “projected winning” candidates have certainly won before any official vote count has been completed, whereas in fact all that is truly known is that those candidates have some degree of likelihood of having won the election; the magnitude of the likelihood (all the way from very reliable to not reliable at all) varies by state because the details of election procedures vary from state to state. This problem has impacts on all non–in-person votes, even those cast weeks before election day—not just late-arriving ones. [59]

C. Structural problems

In 2014, political scientists from Princeton University did a study on the influence of the so-called “elite,” and their derived power from special interest lobbying, versus the “ordinary” US citizen within the US political system. These scientists found that the US looked more like an oligarchy than a real representative democracy; thus eroding a government of the people, by the people, for the people as stated by Abraham Lincoln in his Gettysburg Address. In fact, they found that average citizens had an almost nonexistent influence on public policies and that the ordinary citizen had little or no independent influence on policy at all. [60]

Sanford Levinson claims that next to the fact that campaign financing and gerrymandering are seen as serious problems for democracy, also one of the root causes of the American democratic deficit lies in the US Constitution itself. For example, there is a lack of proportional representation in the Senate for highly populated states like California, as regardless of population all states are given two seats in the Senate. [61]

Partisan election officials in the US can give an appearance of unfairness, even when there are very few issues, especially when an election official like a secretary of state runs for an election that they are overseeing. Richard Hasen claimed that the US is the only advanced democracy that lets partisan officials oversee elections, and that switching to a nonpartisan model would improve trust, participation and effectiveness of the elections. [62]

The Electoral College has been criticized by some people for being undemocratic (it can select a candidate who did not win the popular vote) and for encouraging campaigns to mainly focus on swing states, as well for giving more power to smaller states with less electoral votes as they have a smaller population per electoral vote compared to more populated states. This can be seen through one electoral college vote representing 622,000 voters in California, compared to one electoral college vote representing 195,000 voters in Wyoming. [63]

The first-past-the-post system has also been criticized for creating a de facto pure two-party system (as postulated in Duverger’s law) that suppresses voices that do not hold views consistent with the largest faction in a major political party, as well as limiting voters’ choices in elections. [64]

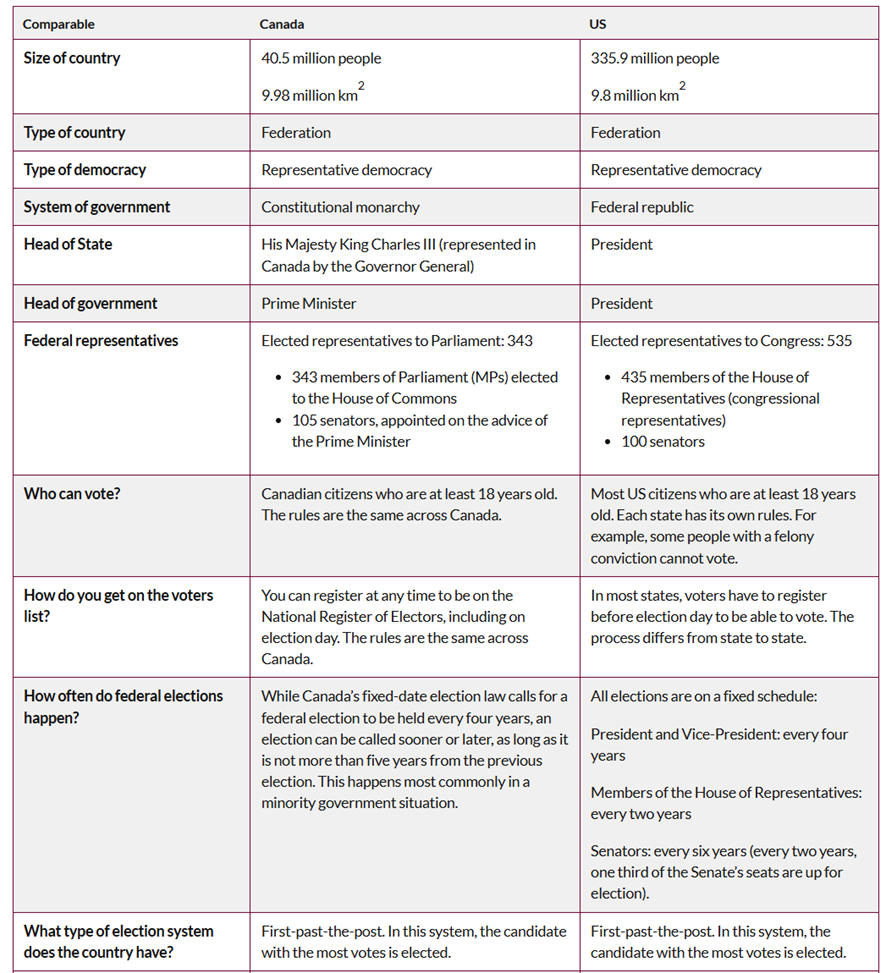

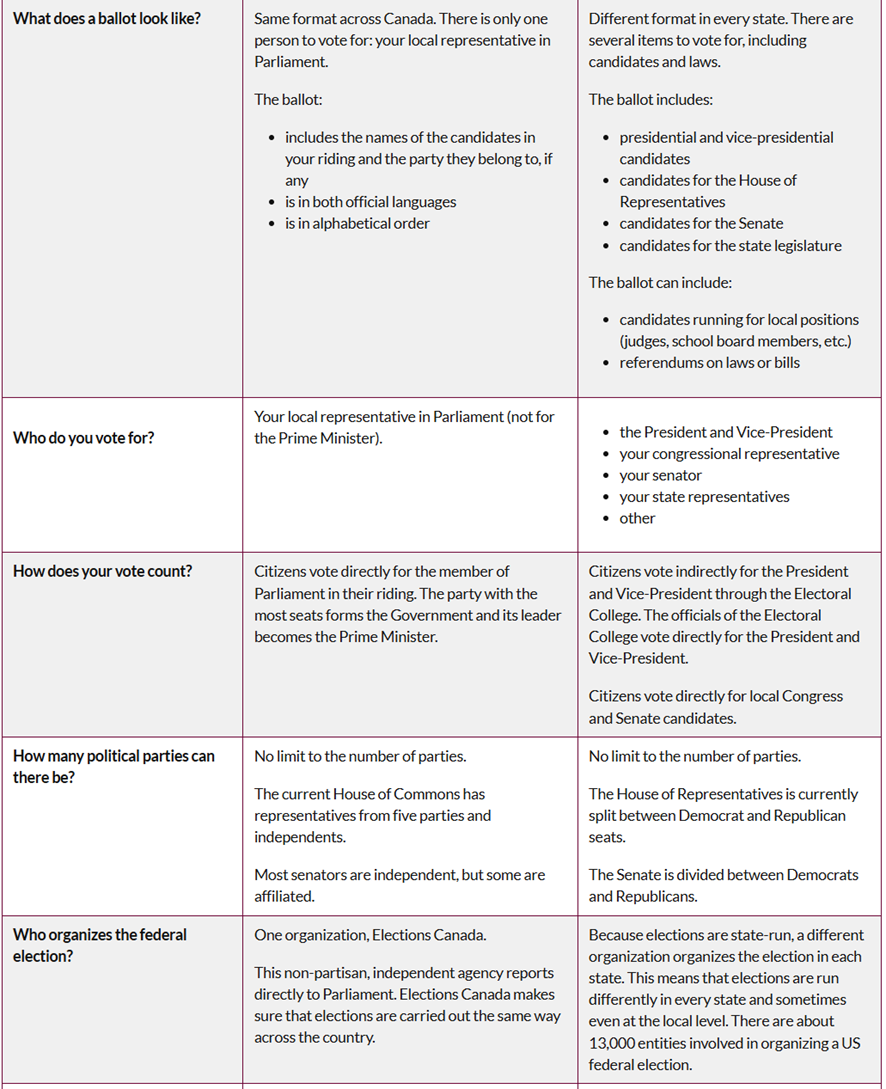

IV. Comparison of US Electoral System with Mexican and Canadian electoral systems

US electoral system has both similarities and differences with Canadian and Mexican systems. All of three countries have federal systems and bicameral legislatures. All elections in these three countries are on a fixed schedule. In addition, Us and Canada have first-the-post voting systems.

However, there are many differences among these three countries. The elections in Canada and Mexico are managed and administered by a national election agency. Thus elections in both Canada and Mexico are carried out the same way across the country. By contrast, elections in the US are managed and carried out by each state in different ways. The biggest difference is that unlike Canada and Mexico, the US elect the head of government (President) though the Electoral College. In addition, unlike the US and Canada, Mexico has a hybrid system across first-past-the-post voting (single-member district), party-list proportional representation, and/or mixed-member proportional representation. Moreover, unlike Mexican members of Congress, members of US congress do not have term limits. Table 4, 5, and 6 show the similarities and differences among the US, Canada, and Mexican electoral systems.

Table 4: Federal elections comparison, US vs Canada (Elections Canada, 2025)

Table 5: Federal elections comparison II, US vs Canada (Elections Canada, 2025)

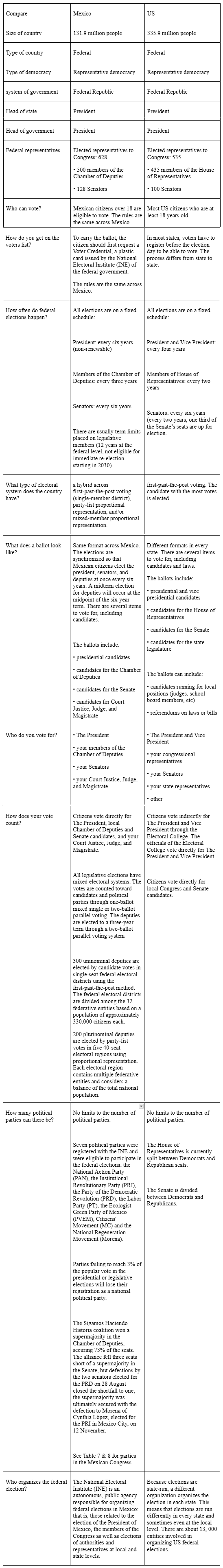

Table 6: Comparison of Federal elections, US vs Mexico (source: Wikipedia)

Table 7: Political parties in the Mexican Senate (source: Wikipedia)

Table 8: Political parties in the Mexican Chamber of Deputies (source: Wikipedia)

V. Conclusion

This paper explained US electoral systems and its features. The paper also explained federal elections in the US, including presidential and congressional and state elections, including local elections. In addition, the paper described the power and role of the US Congress. Moreover, this paper compared US electoral systems with Canadian and Mexican systems and showed the similarities and differences among these three countries’ electoral systems.

[1] "Elections & Voting". whitehouse.gov. April 2, 2015. [2] For more information, see Wikipedia [3] "Constitutional requirements for presidential candidates | USAGov". www.usa.gov. [4] "Electoral College History". National Archives. November 18, 2019. [5] "Maine & Nebraska". FairVote. Retrieved December 31, 2023. [6] For more information, see Wikipedia [7] Ziblatt, Daniel; Levitsky, Steven (September 5, 2023). "How American Democracy Fell So Far Behind". The Atlantic. [8] Statutes at Large, 28th Congress, 2nd Session, p. 721. [9] Neale, Thomas H. (January 17, 2021). "The Electoral College: A 2020 Presidential Election Timeline". Congressional Research Service. [10] "Faithless Elector State Laws". Fair Vote. July 7, 2020. [11] Counting Electoral Votes: An Overview of Procedures at the Joint Session, Including Objections by Members of Congress (Report). Congressional Research Service. December 8, 2020. [12] Neale, Thomas H. (May 15, 2017). "The Electoral College: How It Works in Contemporary Presidential Elections" (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. p. 13. [13] Murriel, Maria (November 1, 2016). "Millions of Americans can’t vote for president because of where they live". PRI's The World. [14] For more information, see Wikipedia [15] For more information, see Wikipedia [16] For more information, see Wikipedia [17] For more information, see Wikipedia [18] For more information, see Wikipedia [19] John V. Sullivan (July 24, 2007). "How Our Laws Are Made". U.S. House of Representatives. Archived from the original on May 5, 2020. [20] Davidson, Roger H. & Walter J. Oleszek (2006). Congress and Its Members (10th ed.). Congressional Quarterly (CQ) Press. [21] "The Law: The President's War Powers". Time. June 1, 1970. [22] David S. Broder (March 18, 2007). "Congress's Oversight Offensive". The Washington Post. [23] "Constitution of the United States". Senate.gov. [24] Wilson Congressional Government, Chapter III: "Revenue and Supply". Text common to all printings or "editions"; in Papers of Woodrow Wilson it is Vol.4 (1968), p.91 [25] Pyser, Steven M. (January 2006). "Recess Appointments To The Federal Judiciary: An Unconstitutional Transformation Of Senate Advice And Consent". Journal of Constitutional Law. 8 (1): 61–114. [26] For an example, and a discussion of the literature, see Laurence Tribe, "Taking Text and Structure Seriously: Reflections on Free-Form Method in Constitutional Interpretation [27] "Complete list of impeachment trials". United States Senate. Archived from the original on December 2, 2010. [28] For more information, see Wikipedia [29] For more information, see Britannica [30] The Legislative Branch Archived January 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The White House. [31] For more information, see Wikipedia [32] For more information, see Wikipedia [33] See https://www.nga.org/governors/powers-and-authority/ [34] For more information, see Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_legislature_(United_States) [35] For more information, see Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_legislature_(United_States) [36] "States with a full-time legislature". Ballotpedia. Retrieved September 25, 2025. [37] Dunleavy, Patrick; Diwakar, Rekha (2013). "Analysing multiparty competition in plurality rule elections" (PDF). Party Politics. 19 (6): 855–886. [38] For more information, see Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elections_in_the_U nited_States [39] DeFalco, Beth (January 9, 2007). "New Jersey to take 'idiots,' 'insane' out of state constitution?". Delaware News-Journal [40] Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe, Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), "ODIHR Limited Election Observation Mission Final Report" VIII. Voting Rights, p. 13. [41] Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe, Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), "ODIHR Limited Election Observation Mission Final Report" IX. Voter Registration, p. 12-13 [42] "Voter Registration Resources". Project Vote Smart. Archived from the original on October 30, 2011 [43] "Louisiana Amendment 1, Citizen Requirement for Voting Measure (December 2022)". Ballotpedia. [44] "Voting Outside the Polling Place: Absentee, All-Mail and other Voting at Home Options". www.ncsl.org. [45] "VOPP: Table 18: States With All-Mail Elections". www.ncsl.org. Retrieved July 2, 2020. [46] "Electronic Transmission of Ballots". www.ncsl.org. [47] "Who Can Vote? - A News21 2012 National Project". [48] Krebs, Christopher Cox (November 29, 2020). "Fired director of U.S. cyber agency Chris Krebs explains why President Trump's claims of election interference are false". [49] Graham, David A. (August 10, 2020). "The 'Blue Shift' Will Decide the Election". The Atlantic [50] "Early Voting Calendar - Vote.org". www.vote.org. [51] Stewart, Charles (2011). "Voting Technologies". Annual Review of Political Science. 14: 353–378. [52] Stewart, Charles (2011). "Voting Technologies". Annual Review of Political Science. 14: 353–378. [53] Stewart, Charles (2011). "Voting Technologies". Annual Review of Political Science. 14: 353–378. [54] For more information, see Wikipedia [55] see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elections_in_the_United_States [56] see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elections_in_the_United_States [57] see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elections_in_the_United_States [58] Stanton, Zack (September 26, 2021), "What If 2020 Was Just a Rehearsal?", Politico [59] Parlapiano, Alicia (October 29, 2020), "The Upshot: How Long Will Vote Counting Take? Estimates and Deadlines in All 50 States", The New York Times, [60] Gilens, Martin; Page, Benjamin I. (September 1, 2014). "Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens". Perspectives on Politics. 12 (3): 564–581. [61] Sanford Levinson (LA Times article available on website) (October 16, 2006). "Our Broken Constitution". University of Texas School of Law -- News & Events. [62] Hasen, Richard L. (2020). "Chapter 2". Election meltdown: dirty tricks, distrust, and the threat to American democracy. New Haven and London: Yale University Press [63] "Representation in the Electoral College: How do states compare?". USAFacts. [64] McDonough, Bryanne (November 4, 2016). "Our Elections Are Stupid: How to Make Them Less Dumb". Reporter.

First published in :

World & New World Journal

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!