Defense & Security

Cooperation Under Pressure: Drug Trafficking, Security, and the Specter of US Intervention in Mexico

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Defense & Security

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Feb.23,2026

Feb.23, 2026

In the bilateral relationship between the United States and Mexico, the word “security” functions as a hinge: it can open doors to cooperation or abruptly shut down any attempt at understanding. The busiest border in the world, a deeply integrated economy, and a public health crisis in the United States associated with fentanyl consumption have, in recent years, shaped a scenario in which interests converge, but where historical mistrust, structural asymmetries, and unilateral temptations also accumulate. Although latent tension between the two countries has long existed, it was not until early January 2026 — specifically after the capture of Maduro by the United States — that this tension became more visible. In Mexico, concern grew over signals and U.S. military “movements” — real, perceived, or amplified by the media — which were interpreted not so much as immediate preparations for a U.S. intervention, but rather as political messages in a context in which political discourse in Washington once again flirts with a high-voltage idea: the possibility of sending troops, carrying out incursions, or executing armed actions on Mexican territory to combat Mexican drug trafficking cartels — recently classified as terrorist organizations in the United States. Many analysts share the view that the relevance of these episodes lies not solely in their operational dimension, but in their symbolic value within a broader strategy of diplomatic pressure.

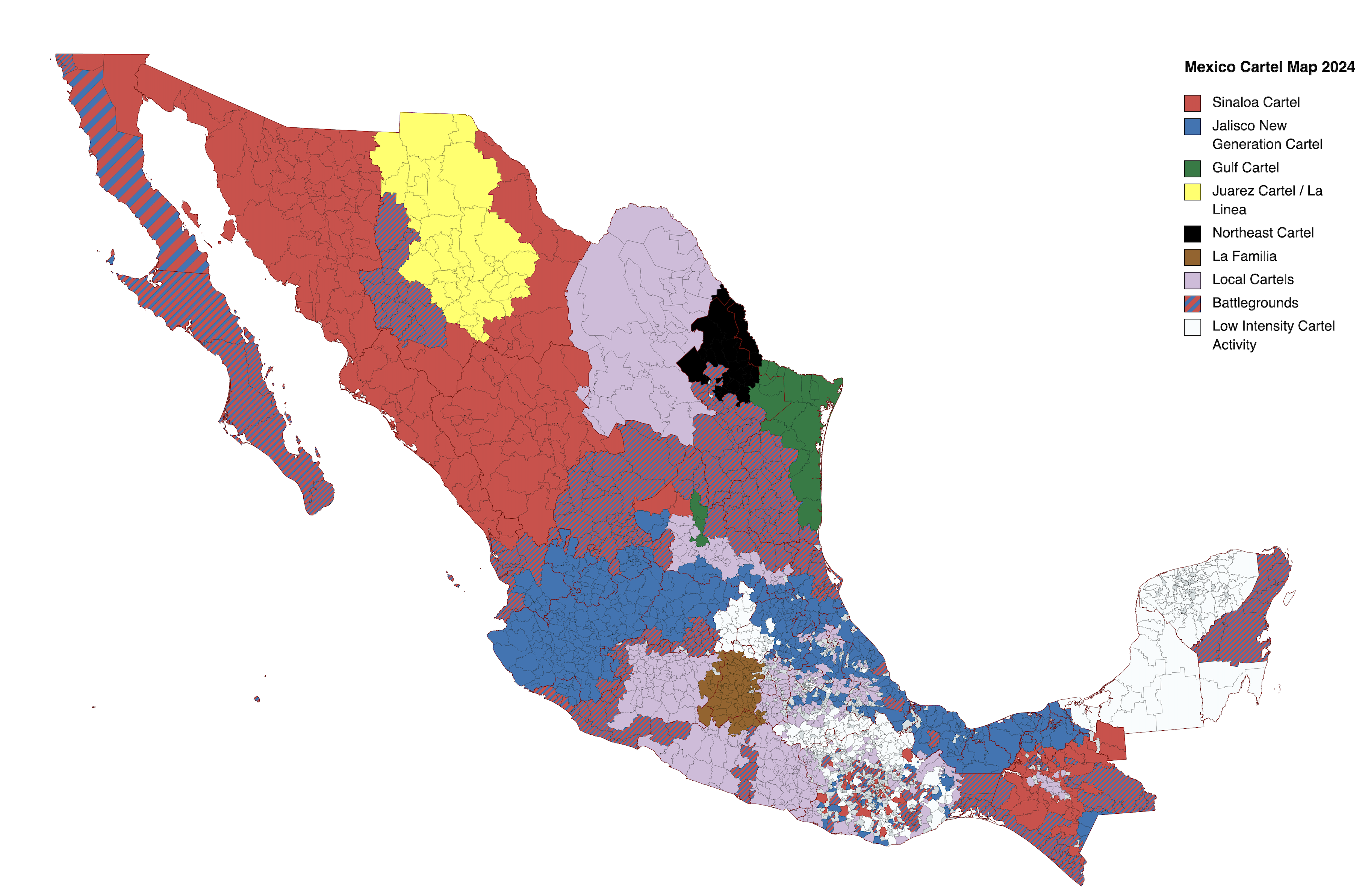

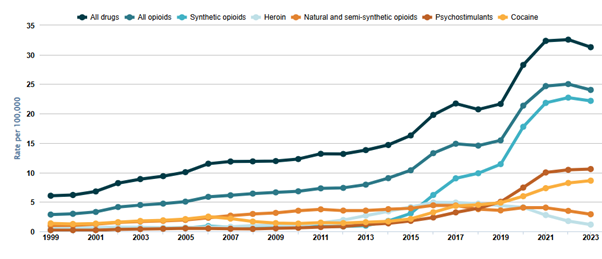

The idea of a U.S. intervention in Mexico has not emerged out of nowhere; in fact, it could be said that there are three simultaneous currents that feed this idea. The first is domestic, inherent to the internal situation of the United States. The fentanyl crisis has become one of the country’s main public health problems, with tens of thousands of deaths annually. This crisis has been used and translated by broad political sectors into a narrative of an external threat. Within this framework, Mexican cartels are portrayed as transnational actors comparable to terrorist organizations, which enables — at least discursively — the use of exceptional tools against them. Moreover, as several analyses published in U.S. media and echoed by the Mexican press point out, this narrative has a clear electoral utility, in which there is pressure to offer “visible” — or tangible — solutions with immediate impact, even when their strategic costs are high. All of this occurs within the context of the fight against drug trafficking. The second current is the Mexican reality. The persistence of high levels of violence and corruption within the institutional apparatus, the fragmentation of territorial control, and the uneven penetration of criminal networks at the local level feed the perception in Washington that Mexico is not doing “enough.” Mexican security policy has oscillated between attempts at territorial control, containment strategies, and the management of a chronic conflict that neither fully resolves nor fully escalates. From the outside, this ambiguity is often interpreted as incapacity or lack of will; from within, on the other hand, it is seen as a pragmatic adaptation to a long-term structural problem. The third current is historical and symbolic. For Mexico, any mention of a U.S. military intervention recalls records of past grievances such as the territorial loss of half of its territory in the nineteenth century, occupations, diplomatic pressures, and episodes of subordination. Therefore, even when bilateral cooperation is intense — and it is — the political margin to formalize or accept a foreign military presence on Mexican territory is virtually nonexistent. Analysts from the Mexican Council and CESPEM remind us and emphasize that the principle of non-intervention is not merely a doctrinal element of Mexican foreign policy, but a pillar of internal legitimacy.

Despite media noise and the dramatization of the public debate, security cooperation between Mexico and the United States is broad, constant, and deeply integrated. For decades, both countries have collaborated in intelligence sharing, border control, judicial actions, the fight against money laundering, and operations against criminal networks, with mixed results. However, the format has recently changed: today, technical and discreet mechanisms are prioritized over large public plans. At the same time, intelligence sharing and operational cooperation are emphasized under clearly defined red lines regarding sovereignty. Even so, this architecture contains a central paradox. The more integrated the cooperation becomes, the more politically fragile it is, as it depends on trust between governments and on the ability of both to justify it before their increasingly polarized domestic audiences. This is why in Mexico, any perception of subordination can erode the government’s legitimacy; while in the United States, any sign of “softness” toward the cartels can turn into electoral ammunition. In January 2026, this dynamic became clearly evident with the transfer of 37 individuals linked to criminal organizations from Mexico to the United States, in a context in which more than 90 handovers had already been recorded in less than a year. Beyond its judicial impact, the gesture — although it had a clear political dimension, aimed at showing tangible “results” to reduce pressure from Washington and deactivate the temptation of unilateral actions — is fundamentally symbolic and masks a deeper dilemma for the Mexican government. From the Mexican perspective, the signal is ambivalent. On the one hand, it seeks to demonstrate that the state retains the capacity to act and can strike criminal structures without accepting foreign military tutelage. On the other hand, it implicitly acknowledges that the bilateral relationship operates under a regime of permanent evaluation, in which U.S. perceptions of Mexican effectiveness condition the level of political pressure and rhetoric. In other words, it is a form of conditional subordination. In the United States, by contrast, these gestures continue to be perceived as insufficient by influential political sectors. The reason is that the problem is measured through indicators that cannot be resolved through mass extraditions: the availability of synthetic drugs, overdose deaths, the industrial capacity of clandestine laboratories, territorial control of routes, or the flow of weapons to the south, among others. Given the influence of these sectors and the impact of the phenomenon on U.S. territory, the issue is often used as a domestic electoral weapon, frequently highlighting “visible” solutions — troops, drones, incursions — without considering their strategic costs.

Speaking about the involvement of drug trafficking in the Mexican state requires analytical precision. It is not a matter of a homogeneous capture of the “government” as a whole, but rather of a fragmented and layered phenomenon. What numerous reports and investigations have documented and repeatedly pointed out is a mosaic of local co-optations with consequences at the national and even international level: infiltrated municipal police forces, regional authorities pressured or bought off, clientelist networks financed with illicit resources, and, in high-impact cases, links to political actors that end up becoming sources of bilateral friction, among many other examples. At this stage of the relationship with the United States, the most explosive political issue is not only the existence of corruption, but the political use of that corruption as a lever of pressure. From Washington, it has been suggested that Mexico should go beyond operational arrests and target political figures with alleged ties to organized crime, even within the governing party — MORENA. However, for the Mexican administration, such a step would entail an extremely high internal cost and the risk of political destabilization, in addition to a potential contradiction of MORENA’s narrative legitimacy regarding its promises of honesty and transparency, which it has strongly defended since coming to power. Here lies one of the core dilemmas. When drug trafficking “invests” in politics, it does not seek only impunity; it seeks governance. Controlling strategic nodes — customs offices, ports, local prosecutors’ offices, police forces, mayoralties — makes it possible to manage violence in ways that are functional to the criminal business. In that context, cooperation with the United States becomes a double-edged sword. While it can contribute to dismantling criminal networks, it can also amplify the narrative of a “failed state,” either through the imposition of external agendas or through the exposure of institutional weaknesses. In turn, this perception, rooted in certain U.S. political sectors, often translates into the promotion of coercive responses or approaches.

Reports of recent, unusual, and amplified U.S. military activity related to Mexico —magnified by regional media and echoed within Mexico — have generated a climate of alarm that goes beyond the immediate plausibility of an intervention. In this environment, what matters is not whether an aircraft, a navigation notice, or a border deployment implies an imminent action, but rather the political message they convey, especially following U.S. military actions in the region and the simultaneous hardening of rhetoric against the cartels. In other words, the demonstration of capability — and the ambiguity surrounding intentions — is being used, or is functioning, as a way to force and extract concessions from Mexico: more cooperation, greater access to intelligence, more measurable results, and greater alignment. From this perspective, the pressure does not necessarily seek to cross the red line of intervention, but rather to come close enough to extract concessions. Consequently, the Mexican response has been repetitive and carefully calibrated: “cooperation yes, subordination no.” This framing, present in official statements and in analyses by national media, seeks to draw clear boundaries without breaking the relationship. It is a defensive — “negotiating” — strategy that acknowledges the asymmetry of power but attempts to contain it within institutional frameworks.

When people speak of an “invasion,” the term tends to polarize more than it explains. In the U.S. debate, however, this word is often more rhetorical than descriptive. In practice, the range of options circulating in the media is broad and, at times, dangerous, precisely because it is gradual: 1. Expansion of the presence of advisers and liaisons in command centers. This is what Mexico can accept with greater political ease if it remains under institutional control. 2. Joint operations with direct participation of U.S. forces (for example, accompaniment during raids). According to reports cited by the media, this is something the United States has sought and Mexico has consistently resisted. 3. “Surgical” unilateral actions (for example, drones or the deployment of special forces against laboratories or criminal leaders). This is militarily feasible but politically devastating. 4. Sustained intervention (what the public imagination calls an “invasion”). It is extremely costly and also difficult to justify legally and politically at present. Moreover, it would trigger a major bilateral crisis. From the above, the greatest strategic risk lies in the intermediate options. “Limited” incursions may appear efficient from Washington’s perspective, but in Mexico they would be interpreted as a direct violation of sovereignty, with effects ranging from nationalist cohesion to the rupture of bilateral cooperation and even incentives for criminal groups to present themselves as defenders of the territory. In such a scenario, a unilateral action by Washington could lead Mexico to restrict intelligence sharing, close operational channels, and turn the issue into a permanent dispute — precisely at a time when coordination is indispensable to strike at the logistical chains of drug trafficking.

President Claudia Sheinbaum has been clear in her repeated rejection of the entry of U.S. troops into Mexico. This stance appears time and again in reports and media coverage that emphasizes opposition to any intervention while supporting cooperation. Moreover, this position responds both to historical convictions and to calculations of internal stability. As previously mentioned, accepting a foreign military presence would entail a high political cost. At the same time, her government has sought to shield the bilateral relationship through visible actions: extraditions, seizures, port controls, and a discourse focused on results. Some media outlets, such as El País, report that Sheinbaum has defended these advances and insisted on “mutual respect and shared responsibility,” reminding that the United States must also address its domestic consumption and the trafficking of weapons from the United States. That last point — the trafficking of weapons — is crucial, as the U.S. firearms market fuels the firepower of cartels in Mexico. For Mexico, insisting on “shared responsibility” is not merely rhetoric or a moral argument; it is an attempt to rebalance the narrative and prevent the problem from being defined exclusively as an external threat originating in Mexico.

Figure 2: Opioid-related and other drug poisoning deaths per 100,000 people in the USA. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics via CDC Wonder Database. https://statehealthcompare.shadac.org/trend/197/opioidrelated-and-other-drug-poisoning-deaths-per-100000-people-by-drug-type#32/1/162,163,127,125,126,129,128/21,19,20,9,10,11,12,13,14,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,15,24,25,27,32,37,42,76/233

Figure 3: Illegal arms trafficking from US to Mexico

In discourse attributed to Trump and his inner circle, Mexico frequently appears as a space where the state is “dominated” by cartels and, therefore, where exceptional action would be justified. This framing appears both in press coverage and in political debate in the United States. However, even within the U.S., there are warnings about the “disaster” that bombing or intervening in Mexico would entail — not only because of the human impact, but also due to the geopolitical consequences of opening a conflict with a key trading partner and a neighbor with whom borders, migration, supply chains, and regional security are shared. Moreover, a military operation in Mexico is not comparable to an “overseas” action. Proximity means that any escalation would have immediate repercussions: border tensions, commercial disruption, migration waves, political radicalization in both countries, and incentives for criminal groups to respond with spectacular violence or low-intensity terrorism, precisely in an effort to break bilateral cooperation.

The United States and Mexico share a structural crisis — synthetic drugs, violence, weapons, migration — but they do not share the same narrative to explain it, nor the same tools to resolve it. Washington tends to frame it as an external threat requiring immediate action; Mexico, by contrast, tends to view it as an internal problem with a binational dimension that calls for cooperation without intervention. As long as these narratives remain unreconciled, the security relationship will continue to be tense, marked by cooperation and distrust at the same time. In 2026, the ghost of deploying troops to Mexico is not merely a military scenario: it is a negotiating tool, an identity symbol, and a test of political strength. The least costly path is not spectacular, but it is the only sustainable one: deep cooperation with clear limits, shared responsibility (drugs, weapons, money), institutional strengthening, and verifiable results that allow both governments to tell their societies they are acting without crossing lines that, once broken, could turn the border into a battlefield. It is also important to remember that drug trafficking is not a conventional army; it is an adaptive criminal economy. Striking one node can fragment and disperse violence. In Mexico, this dynamic has already been observed: the decapitation of leadership can generate succession wars and multiply victims, which is why strategy, risks, and strategic costs must be carefully considered. Ultimately, what is at stake is not only security, but legitimacy: who defines the problem, who imposes the solution, and who bears the political and human costs of carrying it out. Until that dispute is resolved, the bilateral relationship will remain a taut rope, stretched between mutual necessity and historical fear. Finally, an additional element that also weighs on the Mexico–United States relationship is the economic dimension, specifically the future of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA). Its 2026 review has generated political and commercial uncertainty that intertwines with the security agenda, as U.S. pressure is not limited to drug trafficking but also extends to trade and regulatory compliance issues. This could affect Mexico’s economic stability and, consequently, its capacity to respond to the security crisis. The USMCA juncture comes precisely at a moment when bilateral relations — from trade to security cooperation — are under strain. Although a total rupture is unlikely due to deep regional interdependence, the agreement could remain in a limited or “zombie” state, with more frequent reviews and no significant renewals. In this context, defending agreements such as the USMCA becomes a strategic tool for Mexico, allowing it to balance sovereignty, cooperation, and pragmatism in the face of external pressure.

ABC7 Los Angeles. (20 de January de 2026). Crece inquietud en México ante movimientos militares de Estados Unidos. Obtenido de ABC7 Los Angeles: https://abc7.com/post/crece-inquietud-en-mexico-ante-movimientos-militares-de-estados-unidos/18433593/?utm_source=chatgpt.com Canchola Raygoza, D. L. (31 de Octubre de 2025). De AMLO a Sheinbaum: los desafíos que impone el fentanilo a la política exterior. Obtenido de CESPEM: https://www.cespem.mx/index.php/component/content/article/sheinbaum-desafios-fentanilo-pol-ext?catid=9&Itemid=101 Carbajal, F. (16 de Enero de 2026). Desafíos actuales de la Seguridad Nacional en México. Obtenido de E Sol de México (OEM): https://oem.com.mx/elsoldemexico/analisis/desafios-actuales-de-la-seguridad-nacional-en-mexico-27693374?ref=consejomexicano.org Carreño Figueras, J. (13 de Enero de 2026). ¿Intervención? Posible, pero no probable II. Obtenido de El Heraldo de México: https://heraldodemexico.com.mx/opinion/2026/1/13/intervencion-posible-pero-no-probable-ii-758570.html?ref=consejomexicano.org Carreño Figueras, J. (16 de Enero de 2026). EU-México: La presión como diplomacia. Obtenido de El Heraldo de México: https://heraldodemexico.com.mx/opinion/2026/1/16/eu-mexico-la-presion-como-diplomacia-759598.html?ref=consejomexicano.org Carreño Figueras, J. (19 de Enero de 2026). EU-México: un momento preocupante. Obtenido de El Heraldo de México: https://heraldodemexico.com.mx/opinion/2026/1/19/eu-mexico-un-momento-preocupante-760093.html?ref=consejomexicano.org Cázares Luquín, V. (12 de Diciembre de 2025). De la defensa a la acción: México y la reinterpretación del principio de no intervención. Obtenido de CESPEM: https://www.cespem.mx/index.php/component/content/article/de-la-defensa-a-la-accion-principio-de-no-intervencion?catid=9&Itemid=101 Contreras, A. (21 de Enero de 2026). Avión militar de EUA llega a Toluca. ¿Cooperación o alerta? Obtenido de COMEXI: https://www.consejomexicano.org/avion-militar-de-eua-llega-a-toluca-cooperacion-o-alerta/ Corona, S. (24 de Enero de 2026). Sheinbaum marca límites ante amenazas de Trump sobre acciones contra el narco; "México negocia con EU, pero no se subordina". Obtenido de El Universal: https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/sheinbaum-marca-limites-ante-amenazas-de-trump-sobre-acciones-contra-el-narco-mexico-negocia-con-eu-pero-no-se-subordina/?utm_source=chatgpt.com Díaz Santana, A. S. (23 de January de 2026). Intervención militar de EE. UU. en México: la duda ahora es cuándo y cómo se producirá. Obtenido de The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/intervencion-militar-de-ee-uu-en-mexico-la-duda-ahora-es-cuando-y-como-se-producira-274088 Drusila Castro, L. (20 de Enero de 2026). México, ante las amenazas de Trump: “Donde pisa el ejército estadounidense no llega la paz”. Obtenido de El Salto: https://www.elsaltodiario.com/estados-unidos/donde-pisa-ejercito-estadounidense-no-llega-paz El Economista. (23 de Enero de 2026). Intervención militar de EU en México: La duda ahora es cuándo y cómo se producirá. Obtenido de yahoo! noticias: https://es-us.noticias.yahoo.com/intervenci%C3%B3n-militar-eu-m%C3%A9xico-duda-125025443.html Flores Delgado, I. (15 de Junio de 2025). Diplomacia en tiempos de incertidumbre: la política exterior de México frente a la imprevisibilidad del gobierno de Donald Trump. Obtenido de CESPEM: https://www.cespem.mx/index.php/component/content/article/diplomacia-tiempos-incertidumbre-pol-ext-mx-imprevisibilidad-trump?catid=9&Itemid=101 France 24. (10 de Enero de 2026). México en la mira de Trump: demócratas alertan de un potencial "desastre" y Sheinbaum llama al diálogo. Obtenido de France 24: https://www.france24.com/es/am%C3%A9rica-latina/20260110-m%C3%A9xico-en-la-mira-de-trump-dem%C3%B3cratas-alertan-un-potencial-desastre-y-sheinbaum-llama-al-di%C3%A1logo Garrido, V. M. (17 de Enero de 2026). Sheinbaum asegura que hay resultados concretos de seguridad ante la presión del Gobierno de Trump. Obtenido de El País: https://elpais.com/mexico/2026-01-16/sheinbaum-asegura-que-hay-resultados-concretos-de-seguridad-ante-la-presion-del-gobierno-de-trump.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com Gil Olmo, J. (22 de Diciembre de 2025). Corrupción, el talón de Aquiles de Morena. Obtenido de Proceso: https://www.proceso.com.mx/opinion/2025/12/22/corrupcion-el-talon-de-aquiles-de-morena-365063.html Graham, T. (21 de January de 2026). Sheinbaum defends transfer of Mexican cartel members amid efforts to appease Trump. Obtenido de The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/21/sheinbaum-mexican-cartel-trump Gutiérrez Velázquez, M. F. (12 de Noviembre de 2025). Geopolítica global y la política exterior de México: entre dependencia y liderazgo regional. Obtenido de CESPEM: https://www.cespem.mx/index.php/component/content/article/entre-dependencia-y-liderazgo-regional?catid=9&Itemid=101 Latinus_us. (26 de Enero de 2026). Mesa de Análisis con Loret: Dresser, Becerra, Silva-Herzog, Córdova y Aguilar Camín. Obtenido de YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tfd5MI3PbaM Macías Salgado, D. (17 de Diciembre de 2025). México entre Estados Unidos y América Latina: liderazgo regional en un sistema internacional complejo. Obtenido de CESPEM: https://www.cespem.mx/index.php/component/content/article/mx-liderazgo-regional-en-un-sistema-internacional-complejo?catid=9&Itemid=101 Madhani, A. (5 de May de 2025). Trump blasts Mexico’s Sheinbaum for rejecting offer to send US troops into Mexico to fight cartels. Obtenido de AP: https://apnews.com/article/trump-sheinbaum-mexico-drug-cartels-c2113e74cfc122f8f5a9e162644a470f Noticias DW. (12 de Enero de 2026). EE.UU. y México buscan mayor cooperación contra narcotráfico. Obtenido de DW: https://www.dw.com/es/eeuu-y-m%C3%A9xico-buscan-mayor-cooperaci%C3%B3n-contra-narcotr%C3%A1fico/a-75468890 Olivera Eslava, M. A. (23 de Agosto de 2023). México y Estados Unidos: un frente común contra el Cártel Jalisco Nueva Generación. Obtenido de Centro Mexicano de Relaciones Internacionales: https://cemeri.org/art/a-mexico-estados-unidos-cjng-it Pardo, D. (15 de Enero de 2026). "México es el más fuerte y el más débil ante Trump": la encrucijada de Claudia Sheinbaum tras la intervención de EE.UU. en Venezuela. Obtenido de BBC: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/articles/ce3enj4j8g5o Soriano, R. (21 de Enero de 2026). Trump usa las amenazas a México en seguridad para alardear de su poder ante su electorado. Obtenido de El País: https://elpais.com/mexico/2026-01-21/trump-usa-las-amenazas-a-mexico-en-seguridad-para-alardear-de-su-poder-ante-su-electorado.html The New York Times. (15 de January de 2026). The U.S. Is Pressing Mexico to Allow U.S. Forces to Fight Cartels. Obtenido de The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/15/world/americas/us-mexico-cartels.html Treader, V. (12 de Enero de 2026). Intervención en México: "Donald Trump está dispuesto a todo". Obtenido de DW: https://www.dw.com/es/intervenci%C3%B3n-en-m%C3%A9xico-donald-trump-est%C3%A1-dispuesto-a-todo/a-75481087 Wagner, J. (20 de Enero de 2026). México responde a la presión de Trump y envía a 37 delincuentes a EE. UU. Obtenido de The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/es/2026/01/20/espanol/america-latina/mexico-envio-37-narco-trump.html

First published in :

World & New World Journal

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!