Defense & Security

European public opinion remains supportive of Ukraine

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Defense & Security

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Jun.05,2023

Jun.30, 2023

Public support for Ukraine is holding up in allied countries, but preparations should be made for scenarios in which support ebbs away.

As the war in Ukraine drags on, the direct economic cost to Europe and other countries is rising. Through unprecedently high and now long-lasting inflation, the war has increased financial fragility in households across the European Union and risks eroding public support for Ukraine. But the evidence shows that public opinion stands firm.

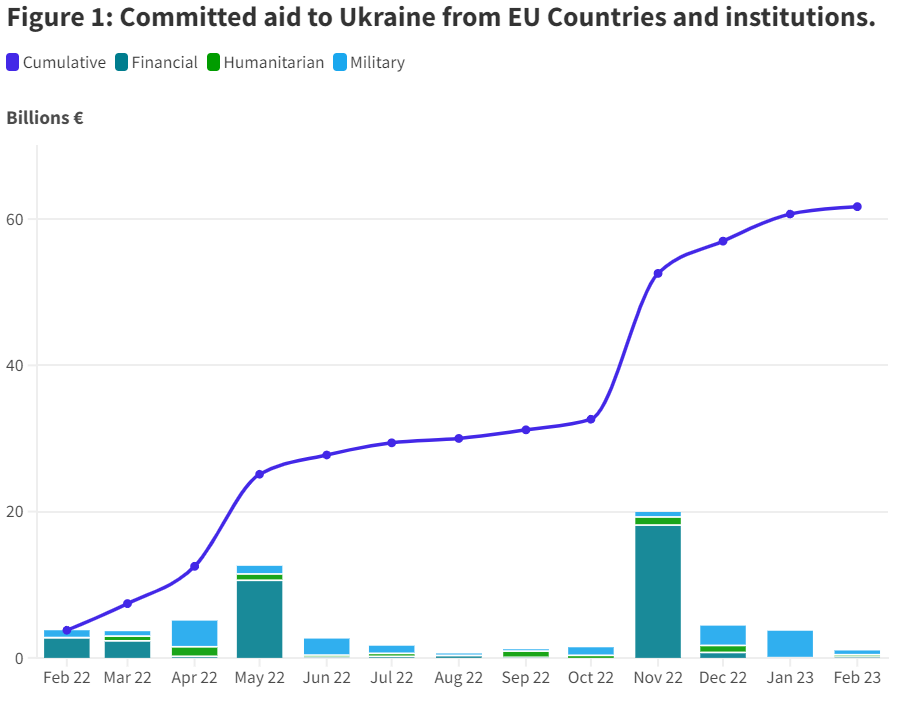

EU countries and institutions have committed financial, humanitarian and military support to Ukraine, totalling €62 billion as of 24 February 2023, exactly one year on from Russia’s invasion. The total is estimated to be around €70 billion as of 23 May 2023.

Source: Bruegel based on Trebesch et al (2023).

Bilateral commitments from EU member states had reached €26.18 billion by 24 February 2023, with most of this figure consisting of military aid (€16.02 billion). Commitments from European institutions hit €35.53 billion in February 2023. The biggest chunk of this was an €18 billion package to support Ukraine’s immediate needs and maintain macroeconomic stability throughout 2023 – one example being the gaping hole in Ukraine’s finances, the budget deficit currently at a quarter of Ukraine’s GDP.

The European Investment Bank has pledged €668 million in liquidity assistance, while a series of €500 million tranches contributed by the EU to the European Peace Facility (EPF) for military purposes now amounts to €3.6 billion committed.

This support is relatively small and sustainable. The €70 billion, encapsulating financial, humanitarian, military, emergency budget and resources for those fleeing the war, is only 0.44 percent of EU GDP.

The European economy has also been affected by high energy prices. The European Commission predicted in its spring 2023 inflation forecasts that euro-area inflation will be 5.8 percent this year. This is a little higher than anticipated during the winter. According to the European Central Bank, euro-area food prices were 15 percent higher in April 2023 than in April 2022.

With euro-area inflation at 8.4 percent in 2022 (European Commission, 2023), €100 in 2021 is only worth €86 in 2023. It is understandable that the public is impatient with the level of costs it faces every day and adapting energy consumption in the face of energy scarcity.

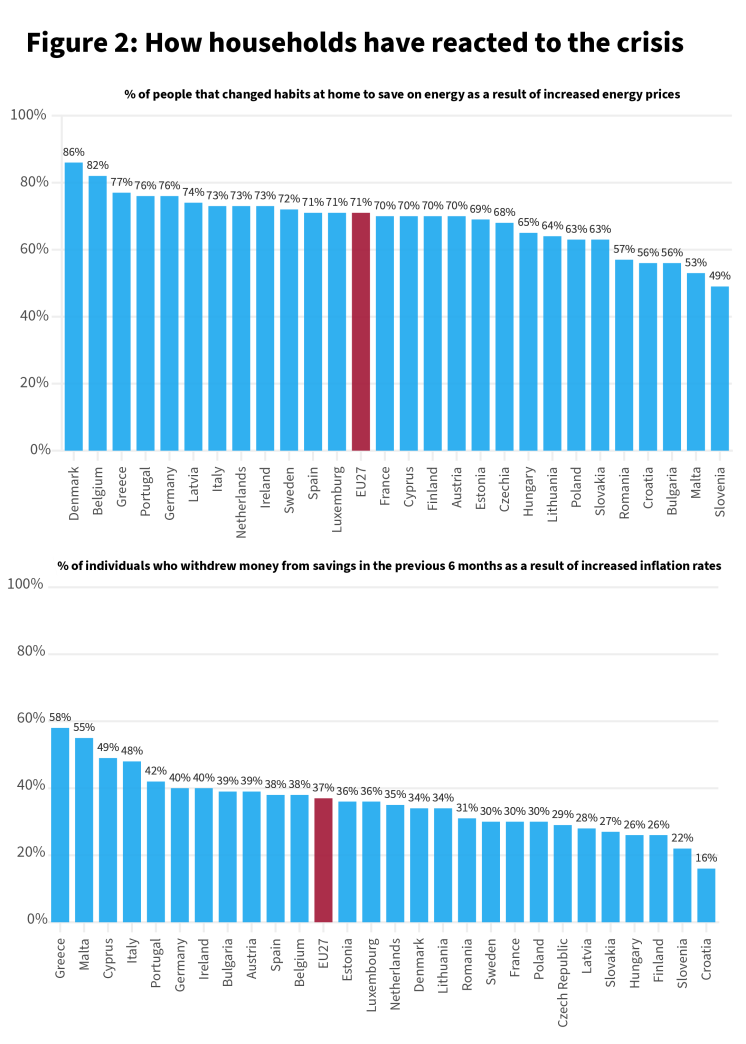

Figure 2 shows the proportion of Europeans who changed their habits to save on energy or dipped into savings due to inflation.

Source: Bruegel based on European Commission (2022). Interviews conducted between 18 October and 4 December 2022 with a representative sample of citizens, aged 18 and over, in each EU country.

Figure 2 shows that 71 percent of EU citizens changed habits at home to save on energy. In only one country, Slovenia, did less than half of citizens change habits (49 percent). Furthermore, 37 percent of EU citizens had to take money from their savings as a direct consequence of inflation, ranging from 58 percent in Greece to 16 percent in Croatia.

The more expensive the war becomes, the more one might expect European public support to decrease. Indeed, there has been an overall decline in support for measures backing Ukraine.

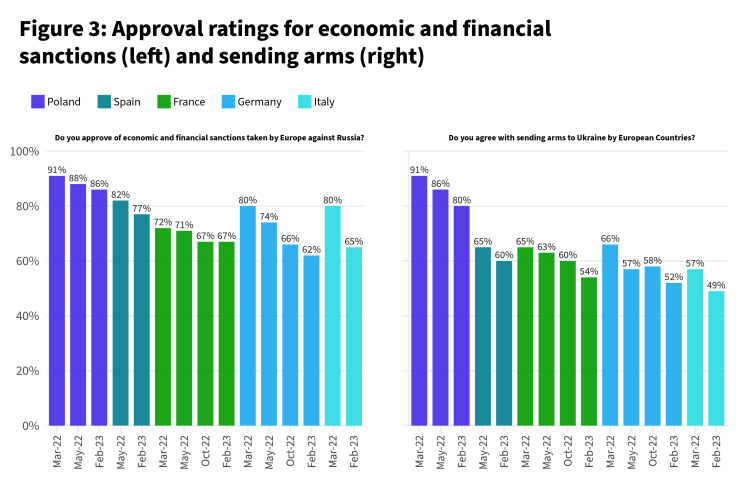

Figure 3 shows a pattern of slow overall decline across France, Germany, Spain, Italy and Poland. The proportion of those in favour of sending arms or of economic and financial sanctions has fallen.

Source: Bruegel based on Ifop (2023).

Despite this decline, as of February 2023, support for sanctions and direct assistance to Ukraine remained solid, above 50 percent in all but one case. EU-wide persistent public support signals that European citizens understand that the outcome of the war is of critical importance to their own futures. Eight months into the war, the average approval rate amongst the EU27 for EU support for Ukraine was an astonishing 73 percent (European Parliament, 2022). Only four countries – Bulgaria, Cyprus, Slovakia and Greece – reported approval ratings of less than 50 percent. Furthermore, an average of 59 percent of citizens in eight Central and Eastern EU countries believe that sanctions against Russia should remain in place according to a poll conducted in March 2023 (Hajdu et al., 2023).

Meanwhile, a poll from the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in February 2023 showed that 87 percent of Ukrainians said that under no circumstances should Ukraine give up any of its territory, even if the war lasts longer. This is an increase from 82 percent in May 2022 .

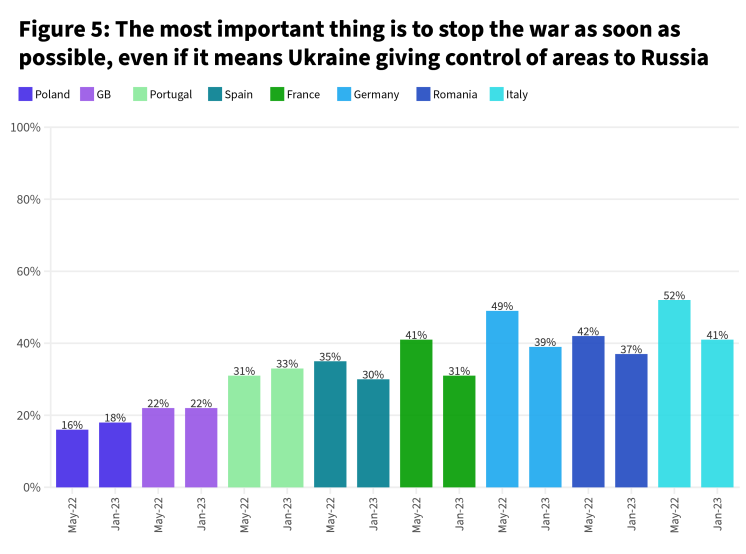

There are some significant disparities in popular support in different EU countries. Krastev and Leonard (2023) noted that three different blocs of public opinion have emerged: the northern and eastern hawks (Estonia, Poland, Denmark and the United Kingdom), the ambiguous west (France, Germany, Spain, Portugal) and the southern weak links (Italy and Romania). Figure 2 shows persistent support in countries from each of these groups.

Amongst even the least supportive member states, some interesting results are observed.

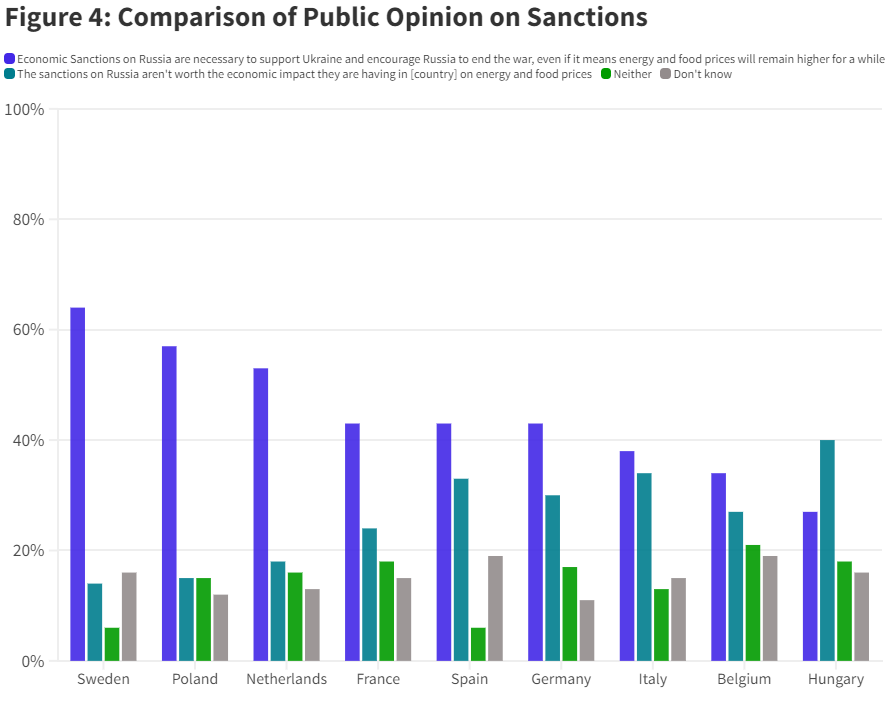

When individuals were asked to choose between two opposing statements on whether sanctions were worth higher prices or not, Hungary was the only one out of nine EU countries surveyed where the majority believed that sanctions were not worth it (Figure 4).

Source: Bruegel based on Ipsos (2023).

Surprisingly, the number of those who believe that the most important thing is stopping the war as soon as possible, even if Ukraine had to forfeit territory to Russia, actually declined almost across the board according to January 2023 polling reported by Krastev and Leonard (2023). Notable declines were seen in Romania and Italy – those characterised as the ‘southern weak links’. This may be due to citizens becoming more willing to support Ukraine for the long run.

Source: Bruegel based on Krastev & Leonard (2023).

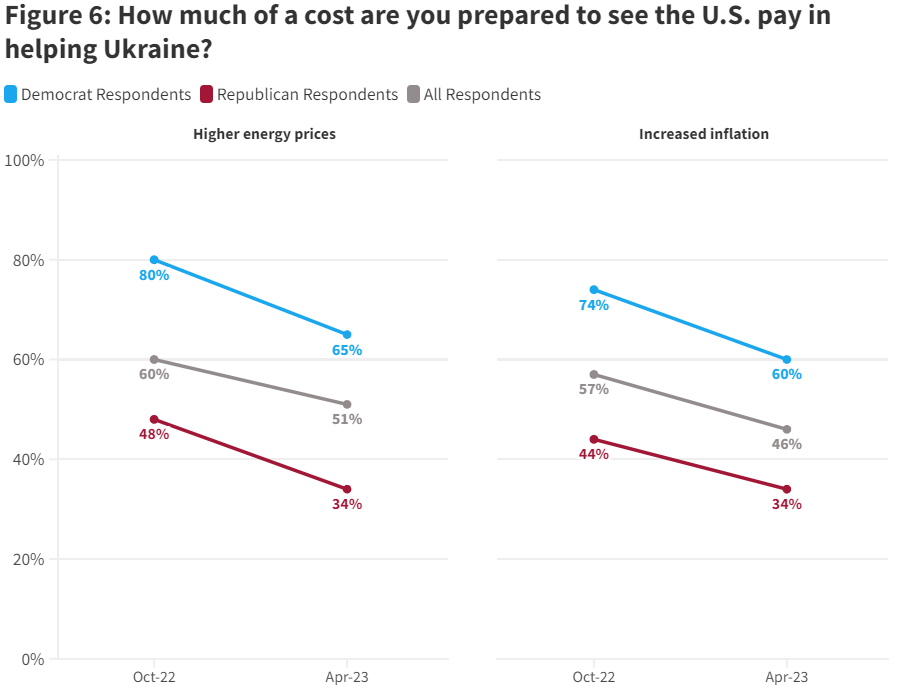

US aid to Ukraine in the first year amounted to 0.37 percent of US GDP (Trebesch et al, 2023). The willingness in the US to bear costs for supporting Ukraine has followed a similar pattern to the EU of slow decline across the political spectrum.

Source: Based on Figure 5, Telhami (2023).

This decline may signal ‘impatience’ with the war in Ukraine (especially amongst Republicans), but there are also signs of persistent support. The current level of US military expenditure to support Ukraine was either too little or about the right level according to 42 percent of respondents, as opposed to 33 percent who said it is too much. Interestingly, there is a strong preference for support staying on course for one to two years (46 percent of respondents) versus only 38 percent who would accept providing support to Ukraine for ‘as long as it takes’ (Telhami, 2023).

Whilst there is a clear division along party lines, there is reduced support amongst Democrats and Republicans. This means that the future of American support for Ukraine may change even before the 2024 elections. Lower support across the political spectrum during the upcoming electoral season could result in reduced backing from the Biden administration or in Congress, as both sides vie for votes. This is before a potential Republican victory, which under certain scenarios, may stop or dramatically limit support from the US.

An erosion in public support for Ukraine might have been expected as the cost and economic consequences of the war began to impact EU households through inflation. But support for Ukraine has remained strong, suggesting that the public understands fully the wider implications for European security of the outcome of the war. The public sides overwhelmingly with the Ukrainians, which are clearly perceived as the victims of an aggression.

This is consistent with the growing support for maintaining or increasing defence spending. Most NATO citizens (74 percent in 2022 versus 70 percent in 2021; NATO, 2023) think that defence spending should either be maintained at current levels or increased (with some significant differences from 85 percent to 52 percent, but always with a majority supporting). Just 12 percent think less should be spent on defence.

Public support could decline more in the future. If news from the battlefield suggests a protracted conflict in which neither side can prevail militarily, then time and the potential decline in US support may affect EU public opinion. A successful Ukrainian counter-offensive would play an important role in the continuance of Western support for the war. In the absence of progress on the battlefield, voices calling for a peace settlement, even on unfavourable terms to Ukraine, might gain traction in the public debate. In upcoming elections, this could benefit political parties less favourable to supporting Ukraine for ‘as long as it takes’.

European leaders must therefore prepare for several scenarios. Significant Ukrainian successes in the battlefield in the near future could pave the way for a positive settlement and the restoration of Ukrainian sovereignty and its reconstruction. The EU must also prepare for the more complex outcome of a protracted war, which would require sustained efforts to support Ukraine militarily (Grand, 2023) and economically. This would require further and constant political efforts to keep public opinion on board, preserving European and Western unity in a potentially degraded economic and political environment.

First published in :

Maria Demertzis is a Senior fellow at Bruegel and part-time Professor of Economic Policy at the School of Transnational Governance at the European University Institute in Florence. She was the Deputy director of Bruegel until December 2022. She has previously worked at the European Commission and the research department of the Dutch Central Bank. She has also held academic positions at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government in the USA and the University of Strathclyde in the UK, from where she holds a PhD in economics. She has published extensively in international academic journals and contributed regular policy inputs to both the European Commission's and the Dutch Central Bank's policy outlets. She contributes regularly to national and international press.

Camille Grand is a Distinguished Policy Fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations. He leads the organisation’s work on defence and disruptive technologies in European security.

Previously, he worked as Assistant Secretary General for Defence Investment at NATO (2016-22), piloting NATO’s work in capability delivery, missile defence, and armament and technology cooperation. He previously was the director of the Fondation pour la recherche stratégique (FRS, 2008-16), the leading French think tank on defence and security studies.

He also held senior positions in the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs as head for disarmament and multilateral affairs (2006-08), and the Ministry of Defence (MoD) as deputy diplomatic adviser to the Minister (2002-06). He has also been a senior adviser on nuclear policy at the French MoD Policy branch and worked as a researcher inter alia at the EU Institute of Security Studies (EU-ISS) and the Institut français des relations internationales (IFRI).

He has been an associate professor at the Paris School of International Affairs (Sciences Po Paris), the Ecole nationale d’administration (ENA) and the French army academy. He has also served on several independent expert groups and boards for the United Nations, the European Union, NATO and the French government. His expertise includes defence and security policy, NATO and EU common defence and security policy, armament and technology, nuclear and missile defence policy, disarmament and non-proliferation.

Luca works at Bruegel as a research assistant. He completed his BA Honours degree in economics and Russian studies at McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

Prior to joining Bruegel, Luca worked as a research intern at the Economic Policy Research Centre in Kampala, Uganda, where he studied the impact of Uganda’s oil and gas exploration on the local agricultural sector. He also worked as a research assistant with professors from McGill University and the University of Saint-Gallen towards constructing a harmonized world labour force survey. These datasets were used to study multiple issues, one example being barriers to structural change out of agriculture due to low, female bargaining power.

Luca is a dual UK and French citizen and is an English native speaker, fluent in French and has good command of Russian.

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!