Diplomacy

Elites vs Citizens: How Singapore and Indonesia are Divided on China

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Diplomacy

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Aug.30,2023

Sep.15, 2023

Surveys show that the elite’s opinion toward China diverges with those of citizens in Singapore and Indonesia. Elites tend to weigh long-term geopolitical strategies and have more access to information, but increased citizen engagement will enhance foreign policy.

Societies are often divided on policy matters — and foreign policy is no exception. American politics have long been divided between the Democrats, who are cautious of U.S. militarisation, and the Republicans, who traditionally tend to support US global military presence. The U.K.’s Brexit referendum saw opinion sharply divided along generational lines, with young people generally preferring to remain in the European Union and the older generation voting to leave. Are similar divisions manifest in Southeast Asia?

Think tanks and research organisations have conducted various surveys to understand how major powers influence the region. Notable ones include the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute’s State of Southeast Asia Survey, Blackbox’s ASEAN Turns 50, the Foreign Policy Community Indonesia’s ASEAN-China Survey, and the Pew Research Centre’s Global Attitudes Survey. Comparisons of these surveys must be mindful of their different objectives, sampling methods, and timing of sample collection. Still, they provide empirical data to explore whether Southeast Asian elites and laypersons have divergent opinions over foreign policies. This article considers how the rise of China is viewed by society in Singapore, the region’s commercial and financial hub, and Indonesia, ASEAN’s largest country and current chair.

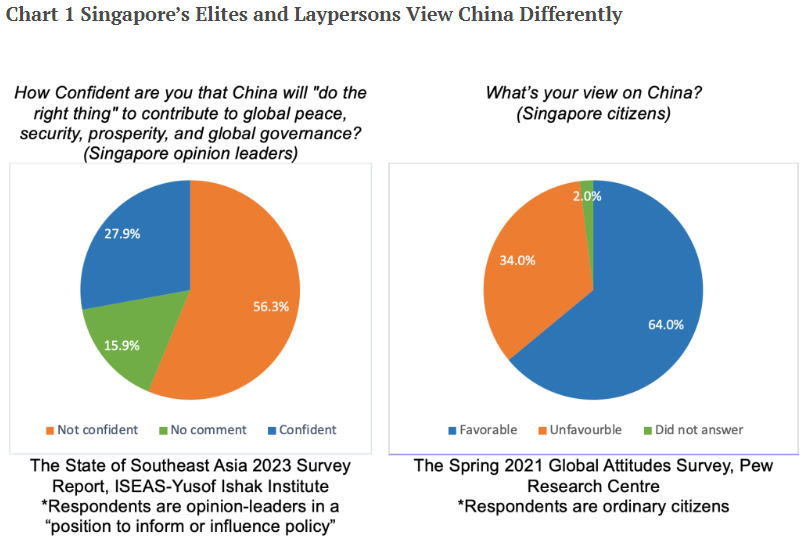

The findings of several polls are quite revealing. The most recent iteration of ISEAS’ annual survey, targeted at the regional elites and policymakers familiar with international affairs, concluded that the region’s trust in China to provide leadership remains low, including respondents in Singapore. However, in contrast, the survey conducted by the Pew Research Centre in 2021 showed that ordinary Singaporean citizens have favourable views of China (Chart 1). This poll, repeated in 2022 on 19 countries (mostly OECD members), found that Singapore was one of three countries that viewed China and President Xi Jinping in favourable terms.

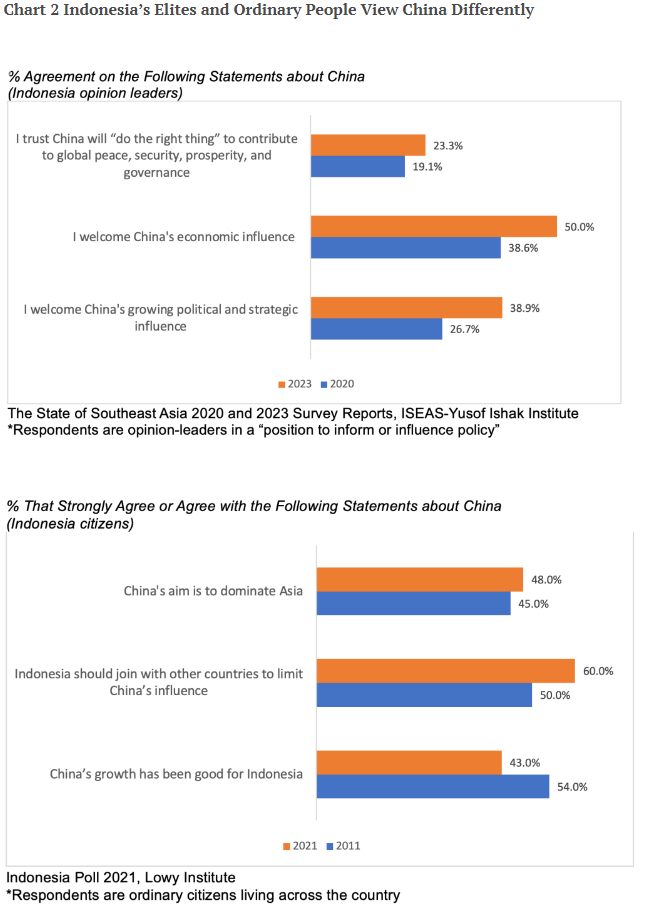

A dissonance can also be observed when comparing surveys in Indonesia – but in this case, the elites’ disposition toward China has grown warmer while the citizens’ mood has chilled over time. The ISEAS surveys concluded that Indonesian elites have become more positive about China in the past three years. Meanwhile, the polls conducted by the Lowy Institute found that ordinary Indonesian citizens tend to be more cautious of China’s influence in their country compared to ten years ago (Chart 2).

What explains these divisions between the region’s elites and laypersons? First, elites and policymakers often project national interests and pursue long-term geopolitical strategies, while some ordinary citizens may prioritise immediate concerns such as economic and social issues. The relationship between Singapore and China is strong, as both sides are indispensable trade and economic partners. Understandably, Chinese economic influence can be felt on the ground. In addition, the social ties between Singapore and China are strong. The majority of Singapore citizens are ethnic Chinese who may still maintain some degree of socio-cultural connection with China.

Second, elites and laypersons have varying degrees of access to information, exposure to disinformation, and interests. Those in foreign policy establishments usually have greater access to information and in-depth analysis, affording them more wide-ranging perspectives on specific issues. Meanwhile, the general public primarily depends on media coverage or word of mouth, which may limit their perspective and sometimes expose them to biased narratives.

In the case of Indonesia’s elites, who tend to be more optimistic over China’s role, their attitudes might be influenced by more nuanced views, for instance, that China’s economic resources are valuable for Indonesia’s economic development and good rapport with China is key to settling the territorial disputes in the Natuna Islands. On the other hand, Indonesia’s laypersons are more wary of China, possibly due to growing concerns over Chinese investments, Chinese natural resource extraction industries, and the influx of Chinese workers taking away local jobs.

While this division might be polarising, the discrepancy can also bring about greater checks and balances between governments’ and citizens’ interests. The cases of Singapore and Indonesia should be a reminder that Southeast Asia is a diverse region at the heart of major power contestations. Taking into consideration different interest groups will help policymakers understand wide-ranging foreign policy preferences so as to better strike strategic balance and neutrality for the region.

Countries in the region must not ignore their citizens’ views when crafting their foreign policies or evaluating whether certain foreign policies resonate well with the public. Several countries have attempted to create platforms for citizens to voice their concerns on foreign policy. The Foreign Policy Community Indonesia (FPCI), developed by the prominent former diplomat Dino Patti Djalal, was established to promote non-government views on international relations and to embrace the Indonesian spirit of civic engagement. The club has chapters in local universities, allowing students to express and channel their thoughts on geopolitical issues. Some Southeast Asian countries also have a network of foreign correspondent clubs, most notably the Foreign Correspondent Club of Thailand (FCCT) founded in the 1950s to be a platform for local and international journalists to discuss international affairs.

The practice of foreign policy is becoming more complex and multifaceted due to increased political tensions between major powers, with greater considerations placed on the nexuses between economics, security, diplomacy, social development, and climate change. Sovereign border lines have become blurred due to greater people-to-people connectivity between countries. The rise of citizen engagement in foreign policy may be a positive development for the region as it would help to moderate foreign policy in the event that governments operate in their own echo chambers.

First published in :

Melinda Martinus is the Lead Researcher in Socio-cultural Affairs at the ASEAN Studies Centre, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute. Melinda’s research interests revolve around sustainable development, smart city initiatives, digitalisation, institutional framework and policy for advancing climate ambition in ASEAN countries.

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!