Energy & Economics

US Semiconductor Reindustrialization: Implications for the World

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Energy & Economics

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Jul.09,2025

Jul.28, 2025

In recent years, US leadership has embraced techno-nationalism amid geopolitical and technological rivalry with China, aiming to minimise reliance on imported chips from Asia. These components are crucial for producing consumer goods, military hardware, and AI systems. The United States set the ambitious goal of developing a self-sufficient semiconductor supply chain during Donald Trump’s first term, and continued under Joe Biden. There is consensus in the United States on the critical role of unfettered access to chips when it comes to ensuring economic and national security. It is unlikely that this technological policy dynamic will undergo significant shifts in the foreseeable future.

Despite a shared objective among both Republicans and Democrats to revive the US semiconductor industry, their approaches diverge significantly. Donald Trump has his own vision for advancing this sector, one that contrasts sharply with Joe Biden’s strategy. For instance, Trump has criticised aspects of Biden-era initiatives, including the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act, which he has called counterproductive. Trump, on the other hand, favours a more aggressive tariff policy and a reduction in federal spending, arguing that major tech companies can do well without additional government support.

The future balance of power—both technological and geopolitical—among the key global actors will be shaped by the development trajectory of the US semiconductor industry.

Biden’s semiconductor legacy

The United States holds a dominant position in chip design, but maintains a relatively modest share in global semiconductor manufacturing—just 10 percent according to SIA data in 2022, and slightly up to 11 percent according to 2025 data provided by TrendForce research firm. Major US tech giants like Nvidia or Qualcomm remain heavily reliant on chips produced in Taiwan. This dependency has increasingly been seen as unacceptable by US leadership, especially in the context of the ongoing tech war with China. Washington now views such reliance as a significant national security risk.

During Donald Trump’s first presidential term, the decision was made to attract leading chip manufacturers—most notably Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s largest contract chipmaker—to set up operations in the United States. This initiative proved successful: in 2020, TSMC agreed to invest $12 billion to build a chip fabrication plant in Arizona (Fab 21).

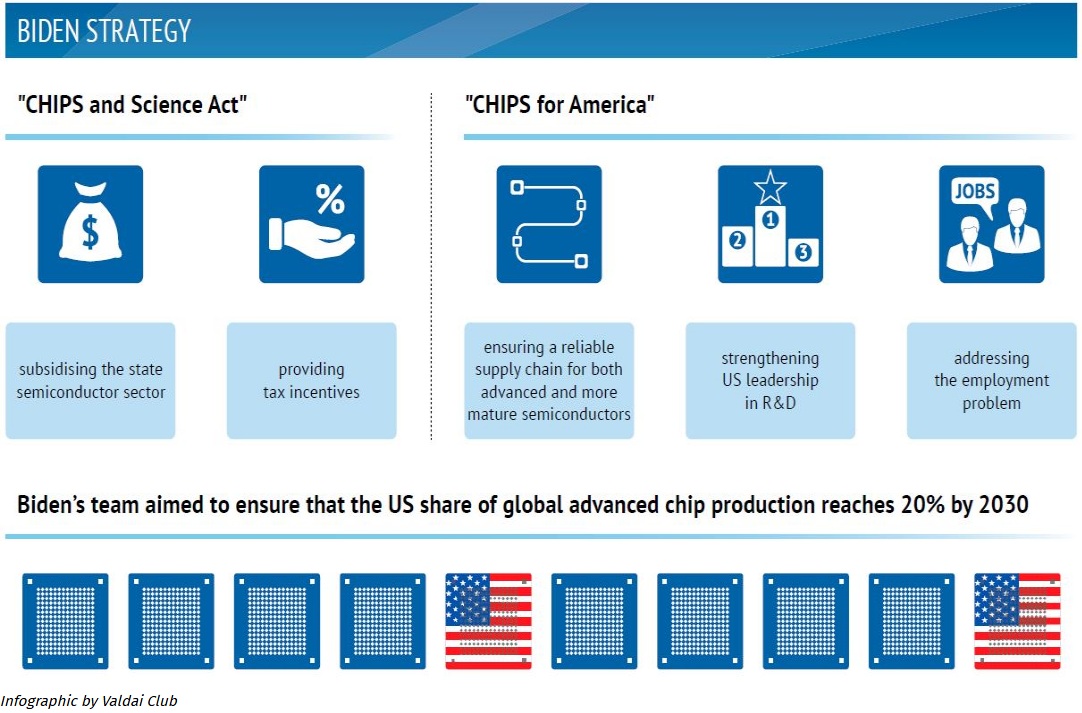

The Biden administration continued Trump’s push to revitalise the semiconductor industry. In August 2022, the CHIPS and Science Act was passed, allocating about $53 billion in government subsidies for the semiconductor sector, along with tax incentives to encourage both foreign and domestic firms to establish chip manufacturing operations on US soil. Additionally, the CHIPS for America programme was introduced to address several key goals, namely, to secure a stable supply chain for both cutting-edge and legacy semiconductors, to reinforce US leadership in R&D, and to boost employment, as investment in the chip industry was expected to generate hundreds of thousands of new jobs in microelectronics-related fields.

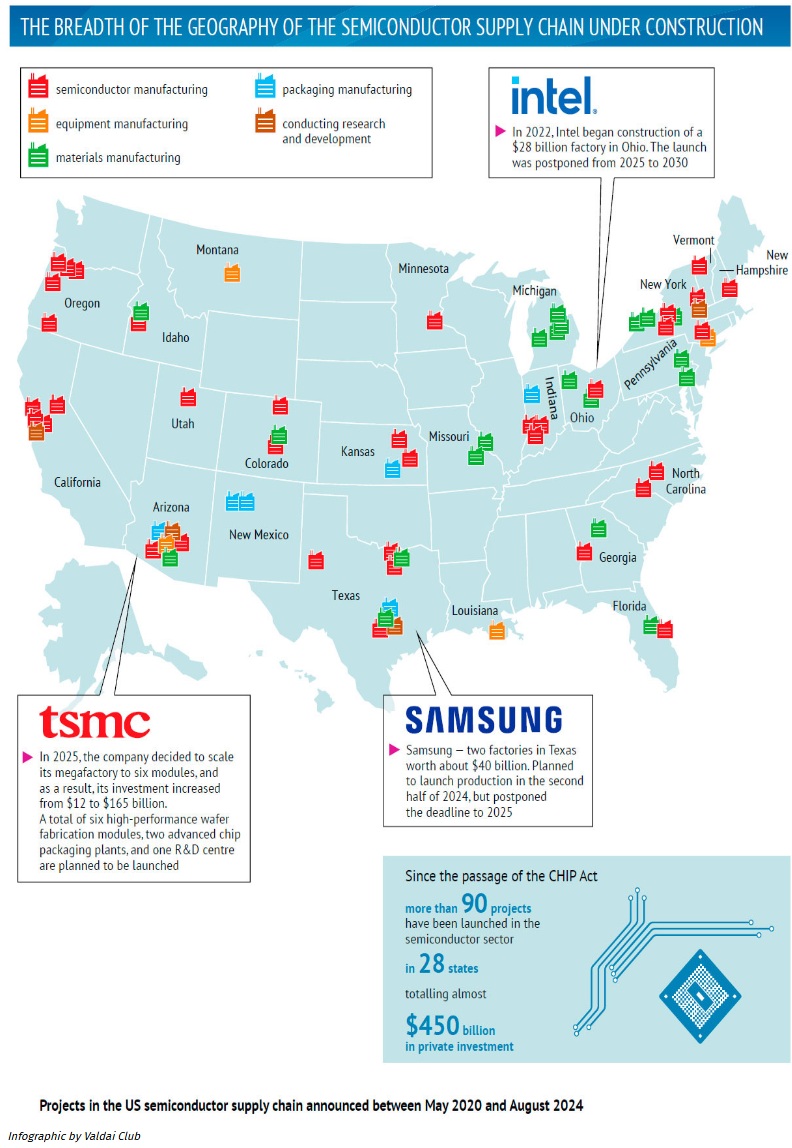

Biden’s programme has borne fruit. Major chipmakers have launched large-scale construction of fabs across the United States. In 2022, Intel started building a $28 billion facility in Ohio; Samsung initiated two plants in Texas worth about $40 billion; and TSMC decided to expand its Arizona site to three modules, increasing its total investment from $12 billion to $65 billion. According to TSMC CEO C.C. Wei, the Arizona facility began mass production in the fourth quarter of 2024 using its N4 (4nm class) process technology, with performance comparable to its fabs in Taiwan. This marks the most advanced semiconductor production facility currently operating in the United States. Plans are in place to launch a second module for 3nm chip production by 2028, followed by a third module by 2030, which will manufacture 2nm and 1.6nm chips and their variants. The Biden team aimed for the United States to capture 20 percent of global advanced chip manufacturing by 2030.

Democrats have adopted a comprehensive approach to rebuilding the semiconductor industry not just focusing on building advanced fabs, but also investing in support areas such as chip testing and packaging, materials production, and R&D. A substantial $13 billion in federal funds has been earmarked for these purposes. For instance, grants and loans were used to support GlobalFoundries’ plans to build an advanced packaging and photonics centre in New York State. Arizona State University also received significant support from the US Department of Commerce, including a $100 million allocation for research and development in next-generation chip packaging technologies.

Wide geographic distribution is a striking feature of the emerging US semiconductor supply chain (Figure 1). Key activities are being established across numerous states: Oregon (semiconductor manufacturing), Idaho (semiconductor and material manufacturing), Utah (semiconductor manufacturing), Montana (equipment manufacturing), Colorado (semiconductor and material manufacturing), New Mexico (packaging), Kansas (semiconductor manufacturing and packaging), Louisiana (equipment manufacturing), Missouri (materials), Minnesota (semiconductor manufacturing),Michigan (materials),Indiana (packaging and semiconductor manufacturing), Ohio (materials and semiconductor manufacturing), Vermont (semiconductor R&D and manufacturing), Pennsylvania (materials), North Carolina (semiconductor manufacturing), Georgia (materials and semiconductor manufacturing), and Florida (materials and semiconductor manufacturing). Among these, several states stand out for their significance and comprehensive involvement: California (semiconductor manufacturing and R&D), Arizona (semiconductor, equipment, and material manufacturing, packaging, R&D), Texas (semiconductor and material manufacturing, packaging, R&D), and New York (materials, semiconductor manufacturing, and R&D).

According to a 2024 study by the Boston Consulting Group commissioned by the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), over 90 projects have been launched in 28 states since the CHIPS Act was passed, totalling nearly $450 billion in private investment.

However, the Biden administration did not pursue full semiconductor self-sufficiency as a goal. There was recognition that recreating the entire supply chain domestically would, even at the initial stage, require a vast amount of time and financial resourcesНадпись: MichiganНадпись: IndianaНадпись: Pennsylvania estimated at around $1 trillion. Therefore, US policymakers have advocated for a collective semiconductor supply chain among allies and partners by building international alliances. In 2022, the Unite States proposed creating the CHIP 4 alliance (United States, South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan), which, with coordinated efforts, could have become a dominant force in the semiconductor industry capable of influencing nearly every segment of the global value chain, with the exception of assembly and testing, where mainland China currently plays a leading role.

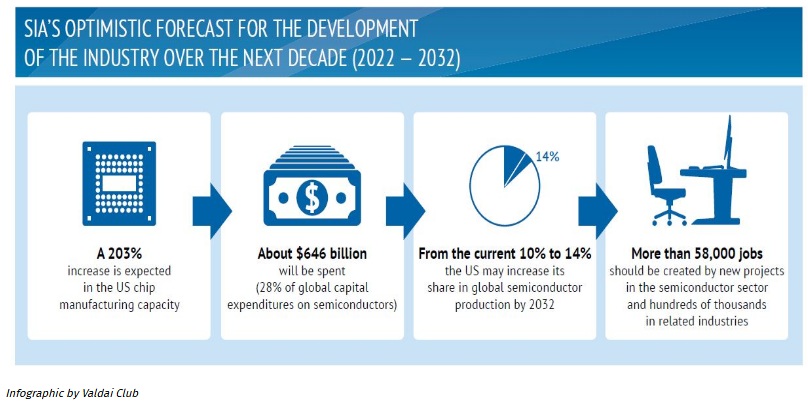

In this way, Trump’s initiative to revive the semiconductor industry has not only continued under Biden, but evolved into a more ambitious and costly programme. The SIA, in its above report, painted an optimistic picture for the future of the US semiconductor sector. It projects that chip manufacturing capacity in the United States will triple over the next decade (2022–2032), growing by 203 percent. This expansion is expected to require $646 billion in investment, or 28 percent of global capital spending in the semiconductor industry. As a result, the United States could increase its share of global chip production from the current 10 percent to 14 percent by 2032. Additionally, experts estimate that the new projects will create over 58,000 new jobs in the semiconductor sector and hundreds of thousands more in related industries.

Despite its ambitious nature, the initial phase of Biden’s semiconductor programme has revealed several challenges. The industry has run into numerous internal obstacles slowing the construction of manufacturing facilities, including a shortage of skilled labour, high labour and construction material costs, bureaucratic hurdles (e.g., obtaining environmental permits), slow disbursement of promised subsidies by the US authorities, union-related delays, cultural differences, and more. These issues have caused delays in launching chip fabrication plants, thereby slowing the pace at which the US can achieve relative technological autonomy in the rapidly evolving semiconductor field. For example, TSMC postponed the start of mass production at the first module of Fab 21 from 2024 to 2025, and delayed the second module from 2026 to 2027–2028. Intel’s costly attempt to reclaim leadership in advanced chip manufacturing has strained its budget, forcing the company to delay its Ohio fab launch from 2025 to 2030. Samsung, initially planning to start production in Texas in the second half of 2024, pushed the timeline to 2025. These delays in fab construction also impacted the schedules of launching supplier plants, including chemical and material producers like LCY Chemical, Solvay, Chang Chun Group, KPPC Advanced Chemicals (Kanto-PPC), and Topco Scientific.

The external component of the Biden administration’s technology policy has also failed to develop as envisioned. After several years of existence, the CHIP 4 has failed to become a multilateral coordination mechanism, and its potential members have not assumed any binding commitments. Only one virtual meeting was held in 2023. The reason lies in internal disagreements within the alliance and concerns about various risks, including geopolitical ones.

Under the Biden administration, the United States made a strong start in the semiconductor sector, launching a wide range of fab construction projects and attracting billions of dollars in public and private investment. However, the process of reviving the US semiconductor industry has proven slower than anticipated. Government subsidies have been disbursed sluggishly, with some companies yet to receive their funding, and the construction of many high-tech industrial facilities has been postponed. Moreover, Biden overestimated the willingness of US allies and partners to join formal technological alliances.

Trump’s radical approach

To encourage both domestic and foreign chip suppliers to set up manufacturing in the United States, Donald Trump, in contrast to Joe Biden, chose coercion (tariffs) over incentives (government subsidies). Criticising his predecessor’s CHIPS Act, Trump argued that companies didn’t need money, but rather motivation in the form of import tariffs ranging from 25 percent to 100 percent. In his view, such measures would compel businesses to invest in US chip manufacturing, especially since these companies have the financial capacity and, therefore, don’t need to rely on government funding.

Almost immediately after taking office, Trump threatened chip manufacturers with higher tariffs. At first glance, this move might seem economically illogical. Why, for instance, punish TSMC—a key partner of major US fabless companies like Nvidia, Apple, and Qualcomm—especially when there is no comparable alternative, either in the United States or globally? Even Intel, despite its struggles, depends on wafers from the Taiwanese firm (its import dependency is about 30 percent).

Yet despite apparent lack of logic, the “stick” approach proved effective. In early March 2025, TSMC announced plans to invest approximately $100 billion to build three new fabs for high-performance semiconductor wafers, two advanced chip packaging plants, and one R&D centre.

This raises the question: did the world’s largest chipmaker really get spooked by Trump’s tariff threats and, therefore, decide to make an unprecedented investment in the US economy? In theory, TSMC—sitting in the centre of the global microelectronics industry—could have passed tariff-related costs on to its American clients, who would have had little choice but to continue purchasing its products due to the lack of viable alternatives. Furthermore, a significant share of TSMC’s semiconductors is not shipped directly to the United States, but instead follows a supply chain tour through Asia, where the bulk of chip packaging, testing, and electronics assembly occurs (this infrastructure is only just beginning to take shape in the United States, and that process is anything but fast). Analysts at Bernstein suggest that political pressure, rather than tariffs themselves, drove TSMC’s decision. That assessment holds some merit, but it appears that a combination of factors was at play.

First, TSMC itself is interested in expanding its global presence. Taiwan’s Minister of Economic Affairs Kuo Jyh-Huei commented on TSMC’s $100 billion investment in the US semiconductor sector by saying, “TSMC already has plants in the United States and Japan, and is now building a new one in Germany. This has nothing to do with tariffs. TSMC’s global expansion is a major development.” Similarly, in 2020 during Trump’s first term, company representatives said that the decision to build a plant in Arizona was “based on business needs.”

Indeed, the move offers several benefits to TSMC, including increased company capitalisation and minimised risks in the event of conflict with mainland China or natural disasters (earthquakes are not uncommon in Taiwan).

Second, the United States remains TSMC’s primary market, and the tariff threat did play its part. In Taiwan, there’s an understanding that when Trump talks about higher tariffs, he isn’t bluffing, because his seriousness was evident during his first term and was experienced first-hand by Canada and Mexico. On April 2, 2025, nearly the entire rest of the world—including Taiwan—faced a new wave of tariffs, with Taiwanese exports to the United States hit by a 32 percent duty (though semiconductors were not yet affected). A 100-percent tariff on semiconductors is unlikely, as it would significantly damage the market value of US tech firms. Still, protective barriers on semiconductors are expected—Trump’s administration has promised to implement them in the coming months. These measures aim to level the production cost of chips between the United States and Taiwan, thereby enhancing the competitiveness of US-made semiconductors.

And finally, TSMC, together with the Taiwanese authorities, is not willing to mar relations with the United States for political reasons. This became evident from TSMC’s earlier decision to support US sanctions against mainland China by refusing to supply its most advanced chips manufactured using 7nm and more sophisticated process technologies even though that market had been a significant source of profit.

After TSMC announced plans to expand its presence in the United States, the Trump administration decided to take more radical action and to scrap the CHIPS and Science Act, a signature achievement of the Biden administration. However, some Republican members of Congress are calling for the law to be preserved, albeit with certain amendments. Trump’s hands are not completely untied in this regard, so it is unlikely he can ignore Congress’s position. Even if the legislation gets amended, the process will likely be drawn out, as the CHIPS and Science Act received bipartisan support and has many supporters among Republicans.

Another strategically important issue for the Trump administration is the competitiveness of domestic manufacturers. According to the Taiwanese leadership, TSMC will continue to expand operations in Taiwan, and the most advanced semiconductor technologies will not leave the country. For “the most powerful AI chips in the world to be made right here in America” efforts will be needed on the part of national champions—and soon. In 2025, the leader in producing the most advanced 2nm chips will be determined. The main contenders in this race are TSMC, Samsung, and Intel. Intel, however, finds itself in a difficult position. The company has been facing serious financial troubles for several years and lags behind competitors in mastering cutting-edge production processes. The year 2024 was one of Intel’s most challenging: it underwent a major restructuring (creating a separate chip manufacturing unit, Intel Foundry), posted record losses of $18 billion, and saw a significant drop in its stock price. As a result, about 15 percent of the workforce, including CEO Pat Gelsinger, was laid off; dividend payments were suspended; and a sweeping cost-cutting plan was launched, including deep cuts in capital expenditures over the coming years and a scaling back of global expansion plans. According to Intel Products CEO Michelle Johnston Holthaus, the company failed to capitalise effectively on the artificial intelligence boom and continues to fall behind its competitors technologically. Although Intel plans to begin 18A (2nm) chip production in 2025, there are no guarantees of competitiveness in power efficiency, performance, yield rate, cost, or timely mass production. In March, media reported that Nvidia and Broadcom began testing certain chip components, but such testing, of course, does not guarantee Intel will secure orders.

Apparently, the Trump administration itself has doubts about the US company’s capabilities, as it has proposed that TSMC acquire shares in Intel Foundry. Negotiations with the Asian manufacturer began only in February 2025, meaning they are still at a very early stage.

What short-term challenges does the Trump administration face in revitalising the US semiconductor industry?

Technological lag

There is a high likelihood that the United States will continue to lag behind Taiwan for several years in the production of advanced semiconductors. TSMC plans to begin producing chips using a 1.4nm process by 2028, while on US soil—if deadlines aren’t pushed back again—the Taiwanese firm will only be producing 3nm chips by that time. Although some hope is being placed on Intel, there is no guarantee that the American champion will be able to compete with TSMC, or that a potential collaboration with TSMC (if it acquires a stake in Intel Foundry) will be successful.

Inadequate production capacity

Experts estimate that the output capacity of TSMC’s factories under construction in Arizona is less than one-fifth of the company’s 5nm and 3nm capacity in Taiwan. According to analysts at Bernstein Research, with the deployment of additional production in Arizona, the United States could raise its self-sufficiency in advanced chip production to 40-50 percent between 2030 and 2032. In the near term, this would only cover about half of the chip demand from US tech giants. Moreover, TSMC has not specified clear timelines or technologies for its US expansion. Intel could partly close the gap, but that depends on how competitive its chips are and how quickly it can overcome its financial difficulties.

Slow rollout of production facilities

TrendForce forecasts that the US share of global advanced chip production could grow from 11 percent to 22 percent by 2030. However, the construction of TSMC’s first Arizona plant took nearly five years, and there are no guarantees that future factories will be built fast enough to double US chip output by 2030.

Labour shortage

Developing a relatively self-sufficient microelectronics ecosystem requires a highly skilled workforce. However, the United States is facing severe staff shortages. By 2030, estimates suggest a shortfall of 67,000 to 90,000 professionals in the semiconductor field.

China’s response to US sanctions

The United States is not the only country leveraging interdependence in the semiconductor industry as a tool of pressure. China is responding in kind, though currently in a relatively restrained manner. In 2024, the Chinese government decided to completely ban exports of gallium, germanium, antimony, and ultra-hard materials to the United States even though the restrictions apply only to direct shipments. These actions not only drive up raw material prices (e.g., antimony prices more than tripled since early 2024), but also force US authorities to consider domestic mining and search for alternative suppliers abroad.

High production costs

According to the SIA, building and operating chip fabs in the United States is 30 to 50 percent more expensive than in Asia. Unofficial reports suggest that chips made at Fab 21 in Arizona cost 10 percent to 30 percent more than their Taiwanese counterparts (more precise figures are not publicly available). The high cost is attributed to expensive construction of facilities, high salaries (US engineers earn three times more than their Taiwanese counterparts, incomplete domestic semiconductor supply chains (some materials must still be imported)—TSMC CEO has complained about it—and complex logistics (finished wafers often need to be sent back to Taiwan or elsewhere for packaging).70 Even if tariffs eventually equalise chip pricing, US fabless companies like Apple or Nvidia may still find it more economical to source chips from Asia, where a properly functioning semiconductor ecosystem already exists—unlike in the United States, where such infrastructure is still in its infancy.

Trump’s current tariff policy

Imposing tariffs could lead to a significant increase in prices for components, equipment, and materials, while also injecting uncertainty into the semiconductor industry. For instance, it remains unclear how semiconductor manufacturers will operate under new tariffs on imported chip-making equipment sourced from the EU, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The cost of such equipment can reach hundreds of millions of dollars—for example, the latest Low-NA EUV lithography machine from Dutch company ASML is priced at $235 million. If Intel, TSMC, and other firms are required to pay import duties of 20 percent or more, chip manufacturing in the United States will become prohibitively expensive, undermining investment plans of the manufacturers that have committed to building advanced fabs on American soil.

Naturally, US officials understand that sharp moves in semiconductor policy—such as an aggressive tariff regime—carry significant risk and could spark a true technological crisis. In April 2025, the US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) launched an investigation under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 to determine the impact of semiconductor imports and related equipment on national security. Interested parties submitted comments, many urging extreme caution in this highly sensitive sector, which depends on a complex global supply chain split across multiple phases and countries. Thus, SIA recommended that any tariffs be phased in gradually to allow the US industry to continue functioning efficiently until domestic production capabilities are fully established. The US Chamber of Commerce called for restraint, warning that comprehensive tariffs on the semiconductor supply chain could damage US industry and undermine cooperation with allies and partners in achieving key national security goals. The Chamber also noted that foreign semiconductor companies have made long-term investment commitments to build capacity in the United States, and that political uncertainty and instability could jeopardise the stated goal of re-shoring semiconductor supply chains.

***

As TSMC founder Morris Chang once said, America’s effort to ramp up its own chip production may well prove to be “a very expensive exercise in futility.”

Microelectronics is one of the most complex industries in the world requiring not only massive financial investment, but also time. For decades, the industry developed within the framework of global division of labour. Now, building a relatively self-sufficient supply chain within a single country could take just as long.

Yet, in the medium and long term, America’s push to revive its semiconductor industry may prove justified. The United States holds a strong position in the sector, and US companies control about 50 percent of the global semiconductor market. Furthermore, the United States remains a powerful magnet for talent, and possesses vast financial and political resources. Some experts believe that over time, the United States could weaken Taiwan’s dominance as the global hub of advanced chip manufacturing.

The resurgence of the US semiconductor industry will reshape the global technological order in three key ways. First, it will trigger a transformation of the global semiconductor supply chain. Second, it will lead to greater US independence from imports of critical technologies, which means erosion of importance of some players in the industry, weakening their “technological shield”. Finally, it will cement US technological superiority in many critical industries, from AI to military systems, accelerating a global technological divide with profound geopolitical consequences.

Indeed, America has the potential to become one of the world’s leading semiconductor production centres, provided that several key conditions are met, such as a favourable geopolitical environment, domestic political stability, and the absence of disruptive black swan events. However, Trump’s risky tariff policy could trigger unpredictable cascading effects, both domestically (e.g., higher prices for electronics and microelectronics products) and internationally (e.g., retaliatory tariffs by US trade partners), posing serious threats for the US semiconductor industry.

First published in the Valdai Discussion Club.

First published in :

Ph.D. in Political Science, Head of the Program (Tech Policy) at the Russian International Affairs Council

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!