Energy & Economics

Brazil’s Seven Strengths that Enable Brazil to challenge the US & US President Trump

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Energy & Economics

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Nov.14,2025

Nov.14, 2025

I. Introduction

On October 6, 2025, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva had a phone call with US President Donald Trump. Two leaders spoke for 30 minutes. During the call, they exchanged phone numbers in order to maintain a direct line of contact, and President Lula reiterated his invitation for Trump to attend the upcoming climate summit in Belem, according to a statement from Lula’s office. At the UN General Assembly in New York on September 23, 2025, two leaders had a brief, unscheduled meeting. President Trump commented that he had “excellent chemistry” with his Brazilian counterpart. Even Trump told reporters that President Lula liked me, I liked him. This Trump’s comment has been interpreted by some analysts as a potential thawing in recent frozen US-Brazil relations. This apparently friendly call and comments from President Trump may signal a turnaround in relations between the two leaders, which have been strained in recent months.

Trump and Lula have been at loggerheads since July 2025, when the US leader imposed 50 percent tariffs on Brazilian exports. In announcing those tariffs on Brazil, Trump cited what he described as a “fraudulent” prosecution of former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.

In addition to sky-high tariffs, Trump tried to further pressure Lula to drop the Bolsonaro case by hitting Brazilian supreme court justices with visa bans and slapping financial sanctions on the judge overseeing the case – Alexandre de Moraes. Ultimately, however, Brazil went ahead with Bolsonaro’s prosecution, and the former president was convicted.

Why did President Trump suddenly soften his stance towards Lula now?

Trump’s softer tone may have been prompted by hard economic realities in US, according to Pantheon Macroeconomics’ chief economist, Andres Abadia. The US depends heavily on Brazil for its coffee and meat imports, and both have taken a hit amid the tariff war. The result: prices have shot up.

Brazil is the largest source of imported coffee for the US – responsible for $1.33billion out of the $7.85billion total coffee imports by the US in 2023, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity. But since the 50 percent tariffs kicked in, Cecafe, Brazil’s council of coffee exporters, said that exports to the US fell by 46 percent in August 2025 and had dropped 20 percent more by September 19, 2025.

Amid that supply crunch, coffee prices in the US rose 21 percent in August 2025 compared with a year earlier, even as overall food price inflation hovered at about 3 percent, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. “The prospect of higher coffee prices,” Abadia said, “would be definitely bad for President Trump.”[1]

Brazil is also the US’s third-largest source of imported meat behind Australia and Canada, according to the US Department of Agriculture. “As with coffee, higher beef prices would hit President Trump,” Abadia told Al Jazeera. Beef and veal prices rose by almost 14 percent in August 2025 compared with a year earlier, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. According to a new survey published on September 29, 2025, by the New York Times and Siena University, President Trump’s approval ratings have fallen recently, with 58 percent of respondents saying they think the country is headed in the wrong direction. “Inflation is definitely biting in the US,” says Abadia. “And anything that can be done to ease the pain, especially as we approach the holiday season, would be seen as positive.” [2]

By contrast, Brazil appears to have weathered Trump’s tariffs better than the US has expected: Its overall exports grew in September 2025, compared with a year earlier, as it expanded its offerings to other markets, including China and Argentina. Lula’s feud with Trump has boosted his popularity, and Washington’s interventions in Brazilian politics have put the country’s conservatives on the back foot. Before next year’s presidential election, Lula is currently polling ahead of his top opponents, although the 79-year-old President has not formally announced his bid.

Abadia believes that there is an opportunity for rapprochement between the two leaders. The most fertile area for compromise may lie in rare earth minerals. Brazil has the world’s third-largest reserves behind China and Vietnam. And for now, they remain largely untapped. “Critical minerals are one area where bilateral interests align,” he said. “The US wants to diversify away from China and play an important role in the Brazilian market.” [3]

Trump has shown a clear interest in rare earths, placing them at the heart of his deal with Ukraine, for instance. Brazil, on its part, wants to emerge as an exporter and supplier of these minerals. “Clearly,” noted Abadia, “that would be a positive for cooperation.” [4]

With these episodes in mind, this paper examines why Brazil can challenge US President Trump and force him to soften his position on Brazil. In doing so, this paper explores seven strengths that enables Brazil to challenge the US as well as US President Trump. Brazil’s seven strengths are as follows: 1. niobium; 2. rare earth; 3. agriculture; 4. oil; 5. ethanol; 6. aircraft industry; 7. leader of BRICS.

II. Overview of Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. Brazil is also the world’s fifth-largest country by area and the seventh-largest by population, with over 213 million people. The country is a federation composed of 26 states and a Federal District, which hosts the capital, Brasília. Its most populous city is São Paulo, followed by Rio de Janeiro. Brazil has the most Portuguese speakers in the world and is the only country in the Americas where Portuguese is an official language. [5]

Brazil is a founding member of UN, the G20, BRICS, G4, Mercosur, Organization of American States, Organization of Ibero-American States, and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries. Brazil is also an observer state of the Arab League and a major non-NATO ally of the US.

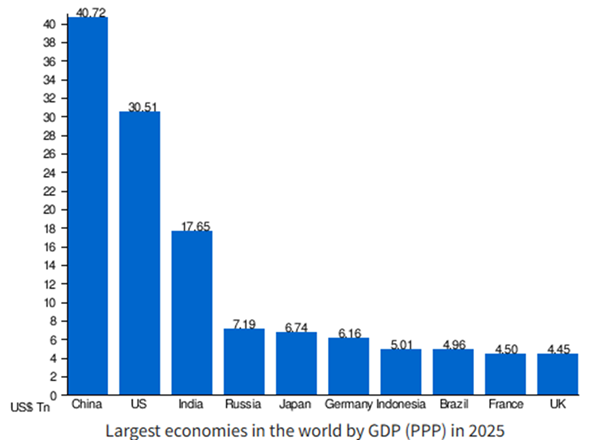

Brazil is a rising global power. As Figure 1 shows, Brazil is the 8th largest economy in the world in PPP terms and the largest economy in Latin America.

Figure 1: Brazil is the 8th largest economy in the world (source: IMF)

Brazil is one of the world giants of mining, agriculture, and manufacturing, and it has a strong and rapidly growing service sector. Brazil is a leading producer of a host of minerals, including iron ore, tin, bauxite (the ore of aluminum), manganese, gold, quartz, and diamonds and other gems, and it exports vast quantities of steel, automobiles, electronics, and consumer goods. Brazil is the world’s primary source of coffee, oranges, and cassava (manioc) and a major producer of sugar, soy, and beef. The city of São Paulo, in particular, has become one of the world’s major industrial and commercial centers.[6]

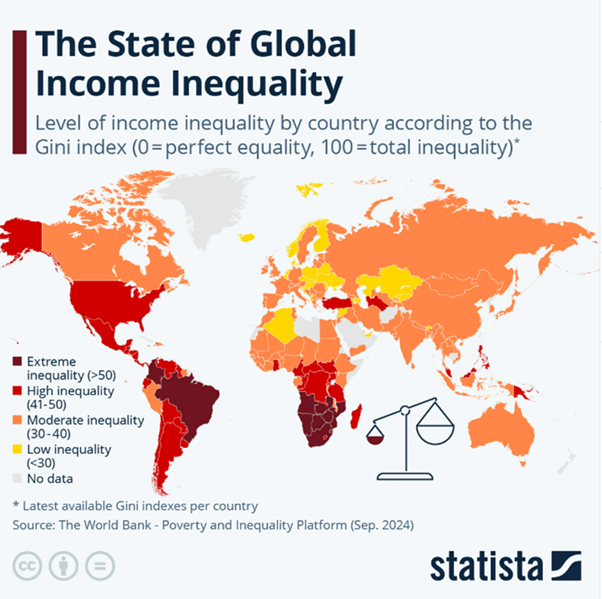

However, Brazil has a lot of domestic problems. Income inequality is very high. As Figure 2 shows, Brazil is one of world’s highest unequal countries along with other Latin American and African countries. The most common tool used to measure different types of inequality is the Gini Coefficient. The Gini Coefficient represents inequality on a scale where 0 equals perfect equality (where everyone has the same wealth, for example). At the other end of the scale, 100 equals a situation of perfect inequality: One person has all the wealth, and no one else has any. Fortunately, income inequality in Brazil, as measured by the Gini index, has dropped. Income inequality in Brazil reached the lowest level in 2024 since the historical series began in 2012, according to Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Last year, the Gini index dropped to 0.506, a 2.3% decrease from the 0.518 recorded in both 2023 and 2022. [7] Nonetheless, Brazil’s income inequality is still very high.

Figure 2: which countries are most unequal. (source: Statista)

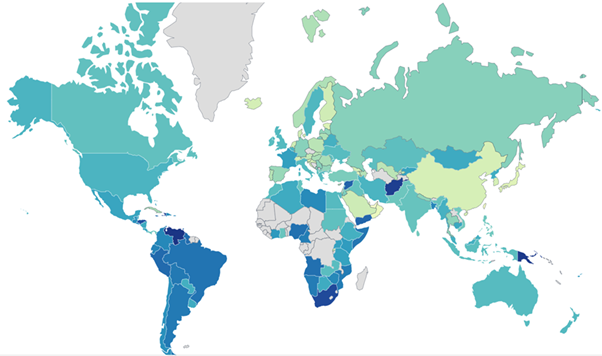

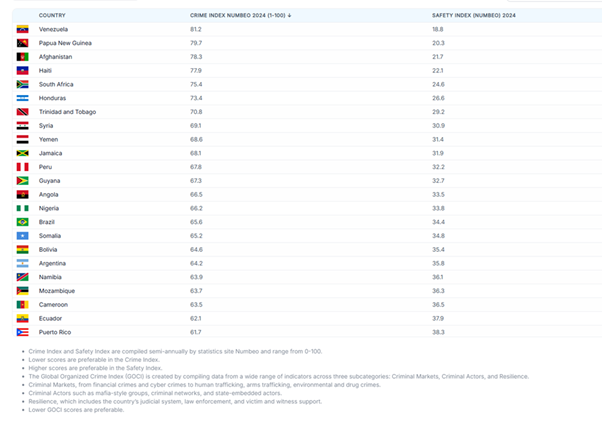

Moreover, crime rate in Brazil has been very high. Brazil had the seventh-highest crime rate in the world in 2020. Brazil’s homicide rate was 23.6 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants in 2020. Brazil’s most massive problem remains organized crime, as it has expanded in recent years, and violence between rival groups is common. Drug trafficking, corruption, and domestic violence are all pervasive issues in Brazil. [8] Luckily the ranking of Brazil’s crime rate was down in 2024. As Figure 3 & Table 1 show, Brazil became a country with the 15th highest crime rate in the world

Figure 3: Crime rate by country, 2024 (source: World population review)

Table 1: Highest crime rate countries in the world, 2024 (source: World population review)

III. Brazil’s Seven Strengths that challenge the US and US President Trump

1. Brazil’s Dominance of Niobium in the world

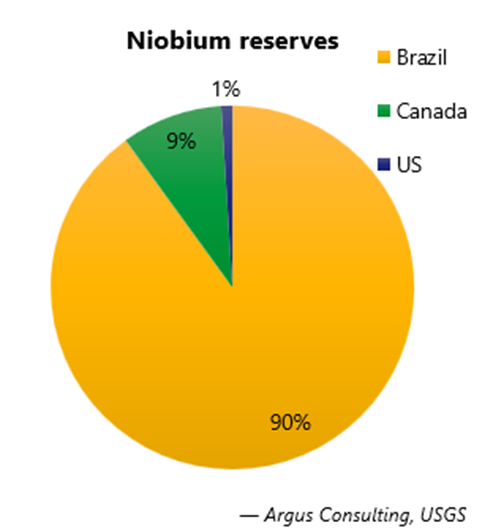

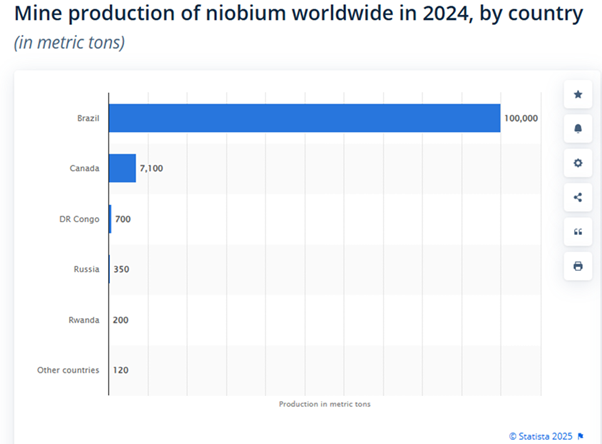

Brazil is one of the world giants of mining. It is a leading producer of a host of minerals, including iron ore, tin, bauxite, manganese, gold, quartz, and diamonds. In particular, Brazil leads the world in reserves and production of niobium as Figure 4 & 5 show.

Figure 4: niobium reserves worldwide by country, 2021 (source: USGS)

Figure 5: production of niobium worldwide by country, 2024 (source: Statista)

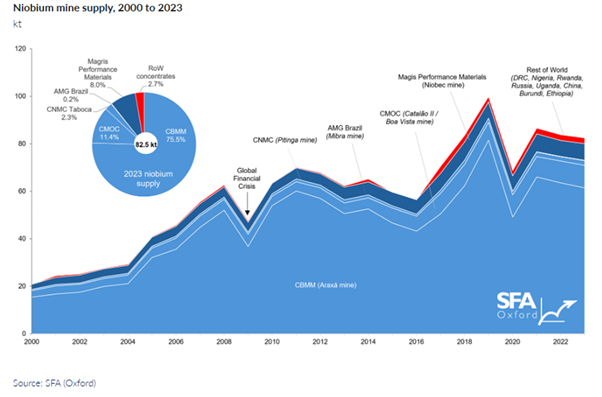

Brazil holds an overwhelming lead, accounting for 90% of global niobium reserves and approximately 85% of its global production. Canada is the sole major producer, supplying most of the remaining 15%. As Figure 6 shows, in 2023, the Brazilian company Companhia Brasileira de Metalurgia e Mineracao (CBMM) supplied 76% of global niobium production, followed by the Chinese-owned CMOC, which supplied 11%. The world’s largest deposit is located in Araxa, Brazil and is owned by CBMM. The reserves are enough to supply current world demand for about 500 years, about 460 million tons. Another pyrochlore mine in Brazil is owned and operated by the CMOC and contains 18 million tons, based on a grade of 1.34% niobium oxide. Canadian production is from one mine. Much smaller production, usually as mixed Nb–tantalum (Ta) ores, comes from Australia and sub-Saharan Africa. The US has had negligible niobium production since 1959, and imported about 9.4 kt (thousand tons) of niobium in 2023. [9]

Figure 6: Niobium mine supply, 2000 to 2023. source: SFA (Oxford)

Niobium (Nb, formerly known as columbium) is a rare metal that is included on the 2022 US Geological Survey’s Critical Minerals List. This light gray crystalline metal is primarily used in alloys with iron (Fe) as ferro niobium to increase the strength, corrosion resistance, and temperature resistance of steel. It is also found in specialty superconducting magnets such as those found in medical MRI instruments.

The extraordinary properties of niobium have rendered it indispensable across a broad spectrum of industrial and technological applications. Its significance became evident in the mid-1930s when niobium was first employed to stabilize stainless steel against corrosion. Later, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, niobium's breakthrough role as a microalloying element (MAE) for steel, typically in the range of 0.05–0.15 wt.%, further solidified its importance. The importance of niobium as an MAE is underscored by its ability to enhance material properties such as high heat and corrosion resistance, increased strength, reduced density, exceptional conductivity, and enhanced biocompatibility. Its presence is essential in the construction of steel structures, including bridges, buildings, pipelines, offshore platforms, and automotive components, where it is predominantly employed as an MAE (∼90 %). [10]

Furthermore, niobium plays a central role in the production of superalloys, holding significant importance in aerospace and power generation technologies. Its exceptional conductive properties also find applications in the healthcare industry, such as in MRI machines and in research institutions. Currently, niobium is finding exciting new applications in the transition to low-carbon energy solutions, and it is already a key component in wind turbines. Ongoing research into niobium-based rechargeable batteries holds the potential for further advancements in sustainable energy technologies, and it is being explored for use in solar panels and smart glass that can filter sunlight radiation and control the amount of light and heat entering buildings. [11]

From its applications in defense systems, where its unique properties are irreplaceable, to its pivotal role in green technologies and infrastructure, niobium’s economic and strategic significance is undeniable. Niobium is essential for the advancement of low-carbon and green technologies. Its classification as a critical mineral stems from both its vital applications and the concentrated nature of its supply. One of its most impactful uses is in steelmaking. The addition of just 0.1% niobium to steel produces high-strength, low-alloy (HSLA) variants, allowing for the construction of lighter, more durable structures. This reduces the quantity of material required, as well as contributes to lower carbon emissions. HSLA steels are particularly valuable for building pipelines, wind turbine towers, and hydrogen gas transmission infrastructure. [12]

Niobium’s contribution to renewable energy systems is also important. Its excellent strength-to-weight ratio makes it vital for wind turbine frames, while in solar and hydrogen technologies, it boosts the efficiency of solar cells and enhances the longevity of hydrogen fuel cells. In sustainable manufacturing, niobium supports the production of high-performance components via 3D printing, reducing both weight and material waste. [13]

The criticality of niobium is largely due to its concentrated supply. Approximately 90% of global niobium production comes from Brazil, with Canada as the only other significant producer. The US has had no domestic production since 1959, and both the US and EU rely wholly on imports. Beyond its scarcity, niobium is difficult to substitute. It is a core material in the defense and aerospace sectors, used in jet engines, missiles, and military systems where few or no viable alternatives exist.

Niobium plays a crucial role in advanced materials and high-performance applications, with demand primarily driven by its use in steel, strategic industries, and emerging technologies. Steel alone accounts for 85–90% of global niobium consumption, serving as a microalloying element to enhance strength, toughness, and weldability. As global regulations increasingly push industries towards lighter and stronger materials, average niobium intensities in steel manufacturing are rising. Currently China is the world’s largest consumer of niobium, with demand propelled by its infrastructure development and car production growth.

Steel remains the backbone of niobium usage, with high-strength, low-alloy (HSLA) and structural steels accounting for the majority share through to 2035. Nevertheless, demand from other sectors, such as aerospace and electronics, is steadily increasing. In particular, interest in niobium for use in batteries is growing, although its uptake heavily depends on the successful commercialization of early-stage niobium-based technologies. Despite steel’s continued dominance, emerging applications begin to expand niobium’s demand profile.

The CBMM, the world’s leading niobium producer, primarily shaped the supply landscape. The company’s strategy centers on aligning production with demand, allowing it to scale output flexibly in response to market needs. This responsive model, however, could pose challenges for new niobium projects seeking investment, as CBMM’s dominant position reduces incentives for alternative supply. Anticipating a significant rise in demand—particularly from battery markets, which are projected to account for 25% of company revenues by 2030—CBMM has already increased its output of battery-grade niobium. [16]

Niobium’s potential in the battery space hinges on its ability to compete with established technologies. Niobium-based anodes offer high-speed charging and long cycle life, often exceeding tens of thousands of cycles. However, their lower energy density than graphite or silicon anodes poses a challenge, especially for electric vehicle applications where energy density is critical. To achieve broader adoption, niobium battery technologies must overcome this performance gap and significantly reduce costs through economies of scale or further technological innovation.

In May 2018, President Trump recognized a group of 35 ‘basic’ minerals considered necessary to US national and economic security, which are to be produced nearby. This order follows Trump’s ‘America first’ initiative to reduce US dependence on imported natural resources, with a US Geological Survey (USGS) report reasoning that 20 of the 23 elementary minerals are sourced from China. Niobium is one of these minerals and was recognized as both critical and essential mineral, indicating its significance to the US, even though it’s not an easy mineral to extract and process. [17]

Niobium’s qualities make it one of the top 8 strategic raw materials considered indispensable. Niobium has been deemed important to the US’s national welfare in part due to their inherent military and industrial potential.

Jeffery A. Green, the president of a bipartisan government-relations firm in Washington DC and a former US Air Force commander, wrote in Defense News that, “with no access to such minerals, including niobium, our precision-guided missiles will not hit their targets, our aircraft and submarines will sit unfinished in depots, and our war-fighters will be left without the equipment they need to complete their missions.”

The scarcity of niobium means that the vast majority is currently imported. The report notes that niobium has not been mined in the US since 1959. Niobium is now imported from Brazil and Canada only. [18]

Vacuum-grade niobium’s role in aerospace is not a newfound revelation. Its unparalleled resilience against extreme thermal stresses, withstanding temperatures over 2,400 degrees Celsius, renders it indispensable for critical components in hypersonic vehicles. Beyond its inherent properties, niobium’s crucial role lies in its use for crafting heat-resistant superalloys essential for hypersonic missiles and the broader aerospace sector. Its low density compared to other refractory metals contributes to a high strength-to-weight ratio, which is essential for reducing the weight of aerospace components. This reduction in weight directly impacts fuel efficiency and payload capacity, two critical factors in aerospace design. For example, companies like SpaceX and Hermeus rely on niobium C103 for their spacecrafts, which require extremely high temperatures that surpass that of other superalloys. [19]

For decades, niobium has played a pivotal role in the US aerospace industry, with its notable use in the innovative designs of the iconic Gemini and Apollo programs of the 1960s and 70s. However, despite its significance, the US depends entirely on niobium imports, with no substantial domestic mining since 1959. This dependence introduces a severe risk to its supply chain. Of the estimated 8,800 metric tons imported annually in 2022, a significant majority comes from Brazil (66%) and Canada (25%). This heavy reliance on just two primary sources—both neighbors of the US—exposes the US to considerable national security and economic vulnerabilities. The situation becomes even more precarious considering China’s dominant position in the niobium sector and its growing footprint in the hemisphere.

China has recognized the potential of niobium for over a decade. In 2011, a consortium of five Chinese firms acquired a 15 percent stake in CBMM. This engagement intensified in 2016 when China Molybdenum Co. Ltd. (now known as CMOC) secured ownership of the Chapadão and Boa Vista mines, further strengthening China’s position in the niobium market.

The importance of niobium was further highlighted in the Brazilian political arena in 2018. Then presidential candidate Jair Bolsonaro emphasized niobium’s role in Brazil’s economic independence. Despite Bolsonaro’s campaign rhetoric focusing on safeguarding this critical commodity from foreign control and advocating for its national governance, Chinese influence in the Brazilian niobium sector continued to grow. By 2020, Chinese entities controlled approximately 26 percent of Brazil’s niobium production. This control not only ensures China’s preferential access and influence over pricing dynamics in the niobium supply chain, but also positions it advantageously in a global context.

China managed to maintain and even strengthen its position at the subnational level under President Bolsonaro. CMOC, for example, provided $1.2 million in Covid-19 aid to the city of Catalão, demonstrating China’s strategic engagement beyond mere commercial interests. China’s influence over Brazil’s niobium production conforms to a pattern of growing ownership and sway over the regional mining industry, a trend with substantial environmental, political, and security implications. Such tactics could force nations into making diplomatic compromises, ceding trade advantages, or grappling with economic dilemmas, thereby solidifying China’s geopolitical standing. The US is not immune to this exposure; the US Geological Survey in 2022 identified niobium as the second most critical of 50 minerals, falling behind only gallium in its criticality to US national security and economic growth. [22]

Facing such formidable challenges, the US cannot afford to remain a passive observer. Safeguarding its strategic interests and maintaining its global position demands a comprehensive and multifaceted critical mineral strategy, in particular in securing niobium supplies.

Incorporating Brazil into the 13-nation Mineral Security Partnership (MSP) could significantly fortify the global niobium supply chain. The MSP represents a concerted multinational endeavor to develop environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards and bolster investments in critical mineral supply chains, an initiative that aligns well with the strategic interests of both Brazil and the broader international community. Brazil’s inclusion would make it the first Latin American country to enter the partnership, signaling its regional leadership and increase in international stature. The integration of Brazil into this partnership is particularly strategic, considering its substantial niobium reserves, in addition to its other critical mineral deposits. This move would add a robust layer of security against potential supply disruptions. [23]

President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s government, with its strong emphasis on ESG standards, is likely to find the MSP’s principles congruent with its policy priorities. The MSP’s emphasis on elevating global standards in these areas could resonate with Lula’s progressive agenda, potentially making Brazil’s participation both beneficial and attractive.

Moreover, Brazil’s inclusion in the MSP would facilitate its adherence to a framework that advocates for the diversification and stabilization of mineral supply chains. This alignment could be important in mitigating China’s dominant influence in the niobium market. By joining the MSP, Brazil would not only assert its role in the global mineral economy but also contribute to a more balanced and less vulnerable critical mineral supply landscape, including niobium. [24]

2. Brazil has the third largest rare earth reserves in the world

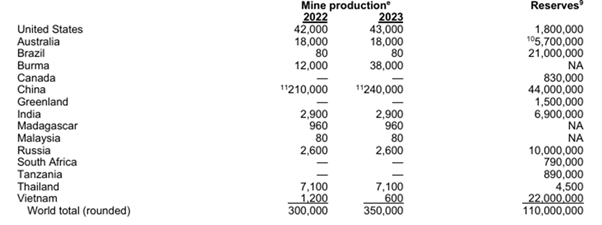

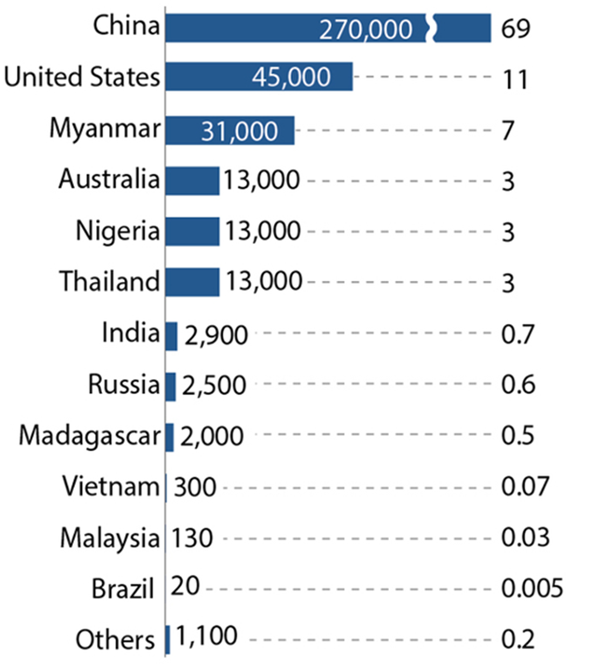

According to US Geological Survey in 2024, China holds the largest rare earth reserves with 44 million metric tons, followed by Vietnam and Brazil. As Table 2 shows, Brazil holds the third largest rare earth reserves with 21 million metric tons. Other countries with significant reserves include India, Russia, and Australia. [25] However, as Figure 7 shows, Brazil ranked 12th position in the world in the production of rare earth minerals.

Table 2: world mine production and reserves of rare earth minerals (source: USGS in 2024)

Figure 7: Global rare earth production by country, 2024 (source: USGS)

Surprisingly, Brazilian rare earth exports hit a record high in 2025, according to data from the Brazil National Mining Agency (ANM). Almost the entire volume was shipped to China.

Exports of raw rare earth materials—part of a group of minerals deemed strategic for the global energy transition—reached $7.5 million between January 1 and June 30, 2025. That figure is ten times higher than the $705,900 recorded in the same period last year, more than double the $3.6 million exported in all of 2024, and higher than in any other full year since official records started in 1997.

Though the total exports remains small, the surge in exports underscores the growing strategic value of these materials. Rare earth elements are critical in high-tech industries, used in wind turbine components and batteries, particularly for hybrid and electric vehicles.

They have also become a flashpoint in US-China trade tensions, which began with President Donald Trump’s tariff war. At one point, China restricted exports of critical minerals to the US in retaliation.

With this background, President Trump said in May 2025 that the US needed Greenland “very badly,” renewing his threat to annex the Danish territory. Greenland is a resource-rich island with a plentiful supply of critical minerals, a category that also includes rare earths elements, under its ice sheet. Trump also signed a “rare earth deal” with Ukraine in May 2025. The tussle over rare earths precedes the current Trump administration. China for years has built up near-total control of the materials as part of its wider industrial policy. [27]

The International Energy Agency said 61% of mined rare earth production comes from China, and the country controls 92% of the global output in the processing stage. There’s two types of rare earths, categorized by their atomic weights: heavy and light. Heavy rare earths are more scarce, and the United States doesn’t have the capabilities for the tough task of separating rare earths after extraction. “Until the start of the year, whatever heavy rare earths we did mine in California, we still sent to China for separation,” Gracelin Baskaran, director of the Critical Minerals Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told CNN. [28]

However, the Trump administration’s announcement of sky-high tariffs on China in April, 2025 derailed this process. “China has shown a willingness to weaponize” America’s reliance on China for rare earths separation, Baskaran said. The US has one operational rare earth mine in California, according to Baskaran. [29]

China holds a near-monopoly control over the global processing of rare earths. In 2023, China produced 61% of the world's raw magnet rare earth elements, which are essential in high-tech industries such as electronics, electric vehicles and defense. Its dominance is even more pronounced in refining these materials, making up 92% of the global refined supply.

The export controls by China could have a major impact, since the US is heavily reliant on China for rare earths. Between 2020 and 2023, 70% of US imports of rare earth compounds and metals came from the country, according to a US Geological Survey report. [30]

The US and Australia have signed a deal intended to boost supplies of rare earths and other critical minerals, as the Trump administration looks for ways to counter China’s dominance of the market. Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said the deal would support a pipeline of $8.5bn (A$13bn; £6.3bn) "ready-to-go" projects that would expand his country's mining and processing abilities. It includes $1bn to be invested by the two countries in projects in the US and Australia over the next six months, a framework text says. The US and Australia have been working on these issues since Trump’s first term, but Albanese said the latest agreement would take the partnership to the next level. [31]

Under this situation, to counter China’s dominance of rare earths, the Trump administration identified Brazil as a potential strategic partner in rare earth production. Despite holding the world’s third-largest reserves—behind China and Vietnam—Brazil accounts for 0.005% of global output in 2024, according to the USGS, as Figure 7 shows. [32]

Accordingly, Brazil's rare earths sector is gaining momentum, with key industry players outlining the country’s potential to become a vital player in the global energy transition. During the Brazil Lithium and Critical Minerals Summit held in Belo Horizonte on June 4-5, 2025, over 300 senior executives and international delegations from China, US, Australia, Canada, the UK, Japan, France, Italy, Portugal, and Argentina discussed Brazil’s abundant resources and the need for strategic partnerships to explore potential reserves and ensure energy security. [33]

3. Brazil: the world giant of agriculture

Brazil is one of the world giants of agriculture. Brazil is the world’s largest producer of sugarcane, soy, coffee, orange, açaí, guaraná, and Brazilian nut. Brazil is also the second-largest producer of ethanol, and third-largest biodiesel producer. Brazil is also one of the top 5 producers of maize, tobacco, papaya, and pineapple. Brazil is one of the top 10 world producers of avocado, cocoa, cashew, tangerine, guava, mango, rice, tomato, and sorghum. In addition, Brazil is one of the top 15 world producers of grape, melon, apple, peanut, fig, peach, onion, palm oil, and natural rubber.

A. Soybean

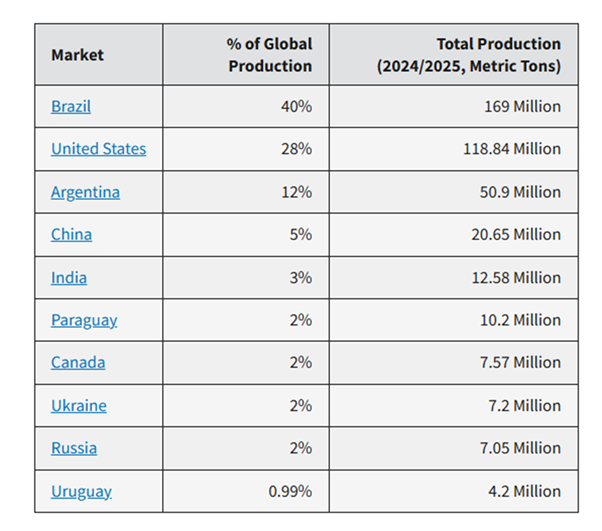

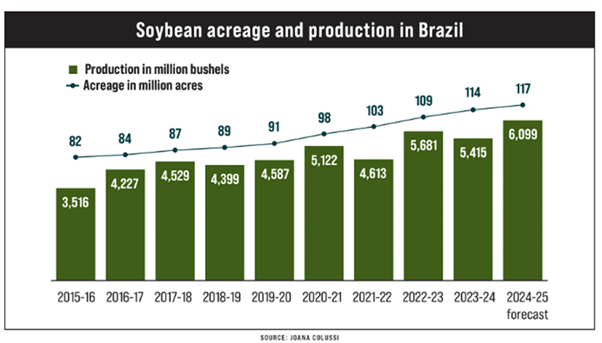

According to USDA (United States Department of Agriculture), as Table 3 & 4 shows, Brazil is the world’s largest soybean producing & exporting country in 2024. This is the results of the increase in production of soybean in Brazil as Figure 8 shows.

Table 3: World’s Top 10 soybean producing countries, 2024-25 (source: USDA)

Table 4: World’s Top 10 soybean exporting countries, 2023-24 (source: USDA)

Figure 8: Soybean production in Brazil (source: Joana Colussi & Fram Progress)

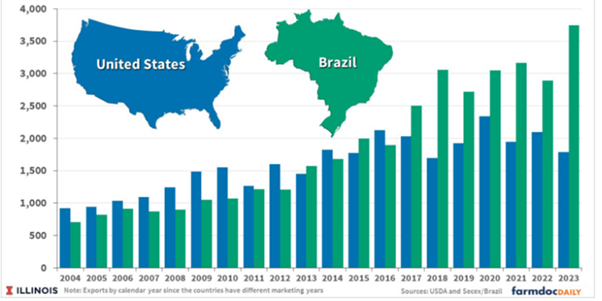

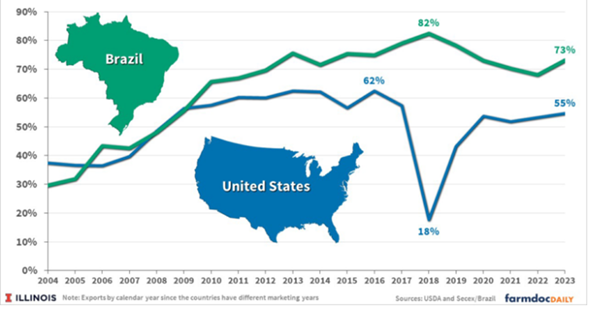

Historically, the US was the world’s largest soybean exporter. In 2013, Brazil surpassed the US in soybean shipments for the first time. Since then, Brazil’s share of the global soybean trade has increased steadily, with Brazilian soybean exports reaching a record 3,744 million bushels in 2023, according to the Foreign Trade Secretariat (Secex). At the same time, American soybean exports were reduced to 1,789 million bushels, half the Brazilian soybean export volume, according to the US Department of Agriculture (see Figure 9). [34]

Figure 9: Total soybean exports by US and Brazil (source: Farmdoc Daily, IL, USA)

Over the last 20 years, Brazilian soybean exports jumped fourfold (431%), from 705 million bushels in 2004 to 3,744 million bushels in 2023. This jump occurred mainly in the second decade. Soybeans have become Brazil’s primary agricultural export commodity by volume, accounting for more than 60% of the soybeans grown domestically. The Brazilian soybean crop for the 2022/23 marketing year was 5,680 million bushels, a historic record, according to Brazil’s food supply and statistics agency. [35]

Revenues from Brazilian soybean exports totaled a record $53.2 billion in 2023 versus $46.5 billion in the previous year, according to the Foreign Trade Secretariat (Secex). Considering the soybean complex, which also includes soybean oil and soybean meal, the revenue reached $67.3 billion in 2023, representing 40% of the total export revenue for the country. For the first time since the 1997/98 season, Brazil displaced Argentina as the leading global exporter of soybean meal due to severe drought, which cut Argentine soybean yields by half. [36]

On the other hand, over the past 20 years, US soybean exports have increased 94% from 922 million bushels in 2004 to 1,789 million bushels in 2023. The US soybean exports have plateaued since 2016, with an average annual volume of 1,993 million bushels. The roughly doubling of exports occurred over the first decade and stagnated in the second decade.

Revenues from soybean exports totaled $27.9 billion in 2023 versus $34.4 billion in 2022, according to the USDA. On average over the past five years, the US has exported 49% of total soybean production. The soybean crop for the 2022/23 marketing year reached 4,160 million bushels, slightly lower than the previous year. [37]

The dynamics of global soybean trade remain heavily influenced by China, which accounts for approximately 60% of worldwide soybean imports. China predominantly sources its soybean supplies from Brazil and the US. For many years, the US was the top supplier, but in the past 15 years China has depended more on imports from South America, especially from Brazil. From 2019-2023, 73% of Brazil’s exported soybeans have headed to China, versus a 51% average for the US (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: China’s share of US and Brazil soybean exports (source: Farmdoc Daily, IL, USA)

Shifting dynamics from China, the top global soybean buyer and consumer, has played a central role in the divergence between the US and Brazil as top global soybean producers.

In 1995, US soybeans accounted for 49% of Chinese soybean imports, with soybeans sourced from Brazil only totaling 2%. The US drought in 2012 kicked off a massive rise in Chinese imports of Brazilian soybeans. As a result, Brazil surpassed US in soybean shipments in 2013 for the first time. By 2024, 71% of China’s soybean imports were sourced from Brazil, with a only 21% sourced from the US. [38]

As China purchased more soybeans from Brazil, Brazilian growers expanded acreage to meet export demand as Figure 8 shows. Moreover, the trade war between US and China in 2018 shifted more soybean production to Brazil at the expense of US soybean acreage as China imposed higher tariffs on US soybean. In 2018, Brazil’s soybean accounted for 82% of Chinese soybean imports while US only 18%. In the middle of another trade war between US and China in 2025, China stopped buying US soybeans. Accordingly, this trend of Brazil’s dominance over the US in soybean exports to China is likely to continue even though China resumed to buy US soybeans in accordance with Trump-Xi trade deal reached on October 30, 2025 in South Korea. [39]

B. Meats

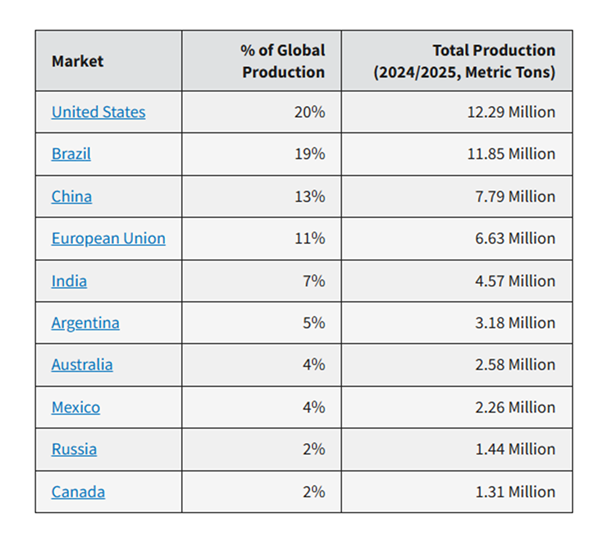

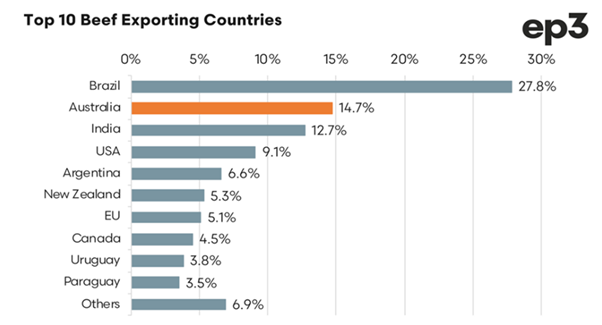

In the production of animal proteins, Brazil is today one of the largest countries in the world. In 2024, Brazil was the world’s second largest producer of beef and the world’s largest beef exporter as Table 5 and Figure 11 show.

Table 5: Top 10 beef producing countries in the world, 2024-25 (source: USDA)

Figure 11: As of December 2024, top 10 beef exporters in the world (source: AuctionPlus)

In 2024, the global beef export market was dominated by five key players, each nation with significant shares of the market. Brazil led the beef market, commanding a substantial 27.8% of global beef exports. Following Brazil, Australia held a notable 14.7% share, positioning itself as a major player in global beef trade. India, another significant contributor, was responsible for 12.7% of the beef exports. The US also played a critical role, contributing 9.1% to the international beef export figures. Argentina rounded out the top five, with 6.6% of the beef market share. These five countries collectively shaped the dynamics of the global beef market, influencing pricing and supply chains. [40]

Brazil sets record for beef exports in 2024 worth US$ 12.8 billion. A total of 2.89 million tons were exported, an increase of more than 26% compared to 2023. The volume exported generated US$ 12.8 billion, approximately 22% more than the amount earned in 2023.

China maintained its position as the main destination for Brazilian beef, with 1.33 million tons exported, generating revenue of US$ 6 billion. Next came the US, which imported 229 thousand tons, totaling US$ 1.35 billion. Other important markets include United Arab Emirates (132 thousand tons and US$ 604 million), European Union (82.3 thousand tons and US$ 602 million), Chile (110 thousand tons and US$ 533 million) and Hong Kong (116 thousand tons and US$ 388 million). [41]

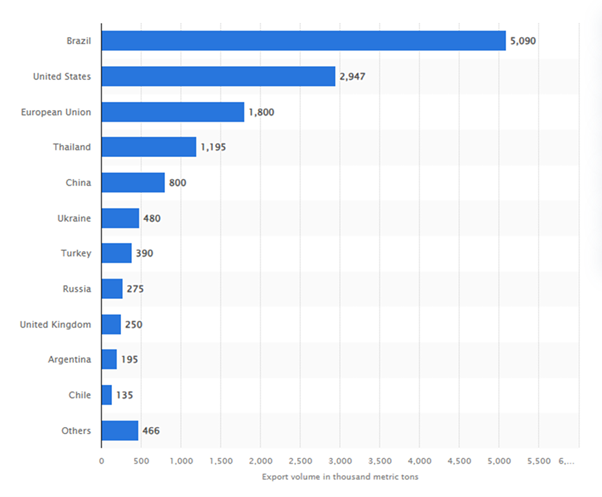

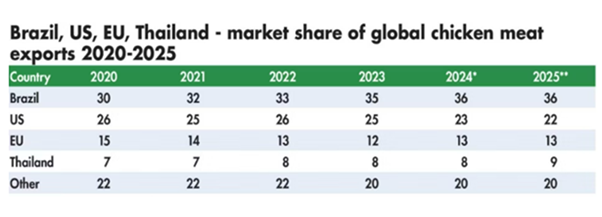

In addition to beef, according to Statista (2025), Brazil was the world’s largest poultry meat exporter as Figure 12 shows. Moreover, Brazil has been the world’s largest chicken exporter during the period of 2020-25, as Table 6 shows. Chicken meat exports reached 5.294 million tons in 2024, generating $9.928 billion in revenue.

Figure 12: Poultry meat exports worldwide leading countries, 2025| Statista

Table 6: Market share of global chicken meat exports, 2020-2025 (source: WATTPoultry)

Over the past 50 years, Brazil has exported nearly 100 million tons of chicken meat to more than 150 nations. Today’s top markets include China, Japan, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and European Union—reflecting global recognition of Brazil’s quality standards and food safety. A significant portion of these exports are halal products aimed at Muslim consumers. More than 2 million tons are shipped annually, making Brazil the world’s largest exporter of halal chicken. [42]

According to Euromeat News on February 18, 2025, the top 10 biggest exporters of halal meat to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) countries account for a total trade value of $14.04 billion. Brazil is the largest exporter of halal meat to OIC countries with a trade value worth $5.19 billion, followed by Australia with $2.36 billion and India with $2.28 billion on the second and third spots respectively. The biggest importer of halal-certified food is Saudi Arabia, followed by Malaysia, UAE, Indonesia, and Egypt. Share [43]

According to SIAL Daily, an Italian newspaper, countries like Brazil and Australia dominate exports of halal-certified meat, especially to Middle Eastern countries. Brazil is the largest exporter of halal products, particularly meat, supplying significant quantities to many countries in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. [44]

Overall, Brazilian meat & soybean exports have dominated the world. As a result, citizens in the world have problems preparing for meals without Brazilian products.

4. Brazil, one of top 10 producer of oil in the world

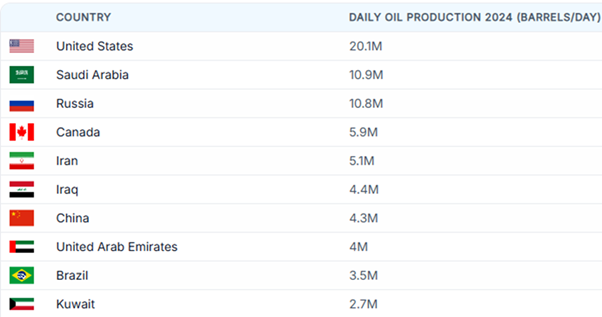

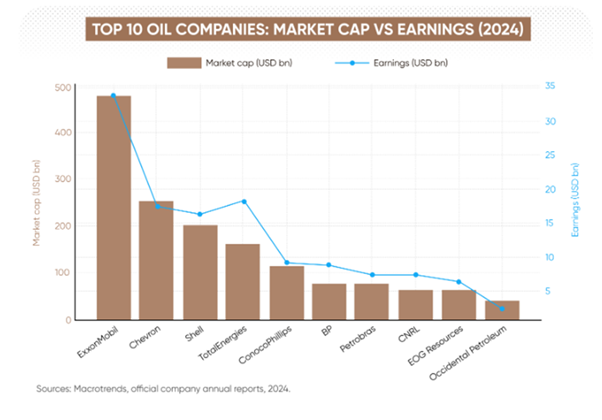

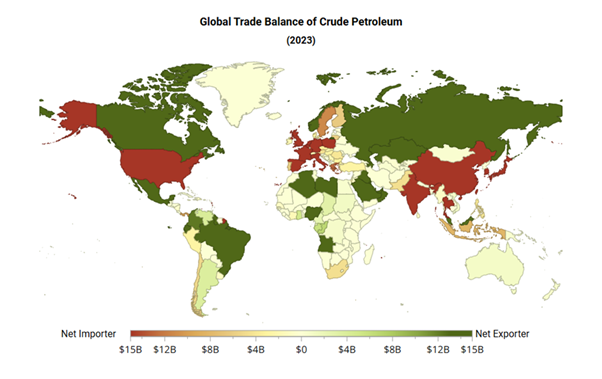

Brazil is one of top 10 influential oil country in the world. In 2024, Brazil was the world’s 9th largest crude oil producer as Table 7 shows. Brazil was also the world’s 10th largest crude oil exporting country, as Table 8 shows. Brazil company ‘Petrobras’ is the world’s 7th largest oil company, as Figure 13 shows.

Table 7: Top 10 crude Oil Producing Countries in the world, 2024 (source: 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy Data - Energy Institute )

Figure 13: Top 10 oil companies in the world, 2024 (source: Macrotrends)

Table 8: Top 10 crude oil exporting countries in the world, 2025 (source: https://www.seair.co.in/blog/crude-oil-exports-by-country.aspx)

Moreover, as Figure 14 shows, Brazil is one of net oil exporting countries. Figure 14 shows the trade balance in crude petroleum for 2023. Colors represent the difference between each country’s export and import values. Shades of green indicate a trade surplus (exports largest than imports), while shades of red represent a trade deficit (imports largest than exports).

Figure 14: Global trade balance of crude oil, 2023 (source: The Observatory of Economic Complexity: OEC)

In 2023, countries with the largest trade surpluses in crude petroleum were Saudi Arabia ($181 billion), Russia ($122 billion), and United Arab Emirates ($96.2 billion).

In 2024, Brazil exported $44.8 billion of crude petroleum, and the main destinations of Brazil’s crude petroleum exports were China ($20 billion), followed by the US ($5.77 billion), Spain ($4.78 billion), and Netherlands ($3.21 billion). In 2024, Brazil imported $8.69 billion of crude petroleum, and the main origins of Brazil’s crude petroleum imports were Saudi Arabia ($1.93 billion), the US ($1.45 billion), Angola ($1.01 billion), and Guyana ($859 million). [45] Brazil exported more crude oil to the world and US than it imported in 2024. Oil trade surplus with the world and US was $36.11 billion and 4.32 billion, respectively.

5. Brazil, the world’s largest producer of sugarcane ethanol

Ethanol is a renewable fuel made from various plant materials collectively known as “biomass.” More than 98% of US gasoline contains ethanol to oxygenate the fuel. Typically, gasoline contains E10 (10% ethanol + 90% gasoline), which reduces air pollution.

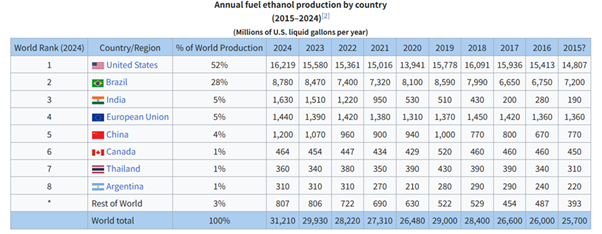

As Table 9 shows, the US was no. 1 producer of fuel ethanol in the world. In 2024, the US produced an estimated 16.2 billion gallons of the biofuel. Brazil was the world’s second-largest ethanol producing country, with an output of 8.8 billion gallons that same year.

Table 9: Annual ethanol fuel production by country, 2015-2024

(source: Annual Ethanol Production | Renewable Fuels Association. https:// ethanolrfa.org/markets-and-statistics/annual-ethanol-production)

However, the US and Brazil have different ethanol industry. Brazil has sugarcane-based ethanol industry, while the US has corn-based industry. Brazil is the leading producer of sugarcane ethanol, followed by such countries as India, Thailand, and Colombia. While the US produces the most ethanol globally, its production is primarily from corn, not sugarcane.

Brazil has the largest and most successful bio-fuel programs in the world, involving production of ethanol fuel from sugarcane, and it is considered to have the world’s first sustainable biofuels economy. [46] Brazil’s sugar cane-based industry is more efficient than US corn-based industry. Sugarcane ethanol has an energy balance seven times greater than ethanol produced from corn. Brazilian distillers are able to produce ethanol for 22 cents per liter, compared with the 30 cents per liter for corn-based ethanol. US corn-derived ethanol costs 30% more because the corn starch must first be converted to sugar before being distilled into alcohol. [47]

Although Brazil has sugarcane-based ethanol industry, its corn ethanol industry has also been expanding rapidly, with production reaching 6 billion liters in 2023, representing an 800% surge over the past five years. [48]

Brazil is also a significant developer of the second-generation ethanol, from sugarcane waste or “bagasse.” This gives it the advantage of being able to produce significantly more ethanol from the same land and, as technology advances, producers are also able to extract more energy from the bagasse. Second generation ethanol, known as an advanced biofuel, is particularly in demand because it meets growing sustainability related regulatory requirements.

This all sounds promising – but it is not to say that the Brazilian ethanol industry is without its challenges. Its great advantages have been the strength of its domestic sugarcane and ethanol production, the availability of a strong internal market and its flexibility. It has also been helped by legislation and regulation. As both the domestic and international ethanol markets change, these advantages continue to prove useful. [49]

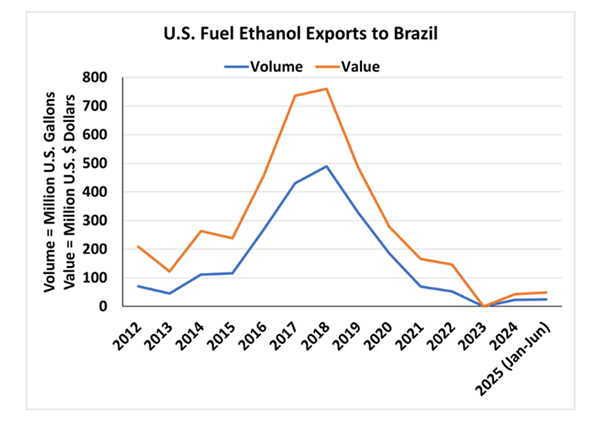

Figure 15: US fuel ethanol exports to Brazil (source: Renewable Fuels Association) https://ethanolrfa.org/media-and-news/category/news-releases/article/2025/08/rfa-supports-u-s-investigation-of-punitive-brazil-trade-practices

The trade volume of fuel ethanol between Brazil and US is low. US exports to Brazil averaged 3,800 barrels per day—or just 2.7% of total US ethanol exports—from January to May, 2024, according to USDA data. As Figure 15 shows, exports to Brazil in 2024 were valued at USD 53 million, down from a peak of USD 761 million in 2018, according to the USTR investigation notice. The US imported just 491 barrels per day from Brazil during the first five months of 2024, equivalent to 81% of total US ethanol imports. [50]

Overall, Brazil shipped about 300 million liters of ethanol to the US in 2024, with the trade flow relying heavily on incentives paid for low-carbon fuels in California. But exports are just a tiny fraction of the size of the domestic market, where so-called flex-fuel cars can run either on 100% ethanol or a mixture of biofuel and gasoline. Historically, most of Brazil’s production has been absorbed by the domestic fuel market where it is sold as either pure ethanol fuel (E100; hydrous ethanol) or blended with gasoline (E27; anhydrous ethanol). Brazil has been a pioneer in using ethanol as motor fuel in what are known as flex fuel engines. [51]

6. Brazil, a major aircraft manufacturer & exporter

The Brazilian aeronautical industry, led by Embraer (Empresa Brasileira de Aeronáutica S.A.), is an outstanding example of successful national industrial production. The commercial aircraft company, which is among Brazil’s main exporters, is recognized as the only large national company with active international insertion in a high technological intensity sector. This leadership position is the result of a historical trajectory that dates back to the 20th century, from the pioneering achievements of Santos Dumont with the creation of the 14-bis airplane to the continuous efforts over the years to develop a sustainable aeronautical industry in Brazil. The initial incentives for the development of the aeronautical industry in Brazil occurred under the government of Getúlio Vargas, through the national-developmentalist model, when two state-owned companies were created: Fábrica do Galeão and Fábrica de Aviões de Lagoa Santa, with the support from the private sector. During the same period, the Aeronautics Technical Center (CTA) and the Institute of Research and Development (IPD) emerged. The two institutions were considered the foundations for the establishment of a modern aeronautical industry in Brazil. Later, the CTA and the Ministry of Aeronautics argued for the creation of a state-owned company in the aeronautical sector, which led to the foundation of Embraer in 1969. [52]

In a post-World War II context, in which aircraft development became more expensive and complex, Embraer faced two challenges during its early years: the growing technological complexity and the greater concentration of the production structure. To overcome these challenges, Embraer developed a strategy which focused on creating its own technologies and intensifying its international operations through exports, resulting in the expansion of its production capabilities and an active global insertion. From the 2000s onwards, Embraer continued to stand out in the development of high-performance technological aircraft and expanded its operations to executive aircraft and the defense sector, transforming itself into an aerospace conglomerate. According to Flight Global, which publishes the ranking of the 100 largest aerospace companies, Embraer reached 3rd place in the ranking of sales of commercial aircraft, behind Airbus and Boeing in 2022. Embraer has divisions for commercial, executive, military, and agricultural aviation; it also maintains an incubator for aerospace technologies and businesses. While Embraer continues to produce aircrafts for the defense sector, it is best known for the ERJ and E-Jet families of narrow-body short to medium range airliners, and for its line of business jets, including the market-leading Phenom 300. As of May 2024, Embraer has delivered more than 8,000 aircraft, including 1,800 E-Jet planes. [53]

On the other hand, concerning aircraft exports, Brazil ranked 7th in 2022, behind France, Germany, Canada, Spain, US, and Ireland. And Brazil ranked 9th in the world in the aircraft/spacecraft exports in 2023. [54] Moreover, as Table 10 shows, according to Aerotime, Embraer is the 7th largest aircraft manufacturer in the world in 2025. [55]

Table 10: Top 10 Aircraft Manufacturers in the World, 2025 (source: Aerotime)

7. Brazil, the leader of BRICS

BRIC was originally a term coined by British economist Jim O’Neill and later championed by his employer Goldman Sachs in 2001 to designate the group of emerging markets. The first summit in 2009 featured the founding countries of Brazil, Russia, India, and China, where they adopted the acronym BRIC and formed an informal diplomatic club where their governments could meet annually at formal summits and coordinate multilateral policies. In April 2010, South Africa attended the second BRIC summit as a guest. South Africa joined the organization in September 2010, which was then renamed BRICS, and attended the third summit in 2011 as a full member. Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, and the United Arab Emirates attended their first summit as member states in 2024 in Russia. Indonesia officially joined BRICS as a member state in early 2025, becoming the first Southeast Asian member. The acronym BRICS+ (in its expanded form, BRICS Plus) has been informally used to reflect new membership since 2024. [56]

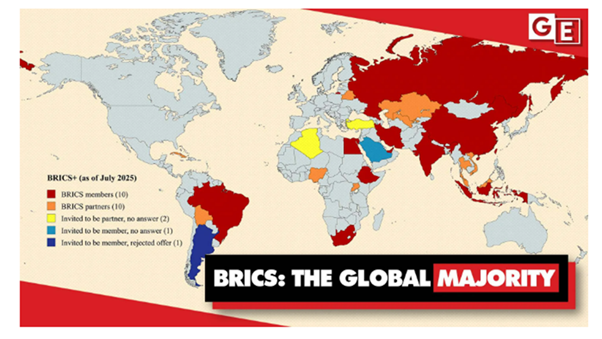

As Figure 16 shows, BRICS now consists of 20 countries. The 10 BRICS members are the founding five — Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa — plus Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates. The 10 BRICS partners are Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Uganda, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam.

Figure 16: BRICS PLUS as of July 2025 (source: Geopolitical Economy)

Some in the West consider BRICS the alternative to the G7. Others describe the organization as an incoherent joining of countries around increasing anti-Western and anti-American objectives. BRICS has implemented competing initiatives such as the New Development Bank, the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement, BRICS PAY, the BRICS Joint Statistical Publication and the BRICS basket reserve currency. [57]

BRICS has been growing in size and influence, and this has frightened some Western politicians. Donald Trump is particularly rattled. After he returned to the White House for his second term as US president, Trump threatened very high tariffs on BRICS, and falsely said he had destroyed the organization. Although Trump threatens BRICS, it grows stronger, resisting US dollar. [58]

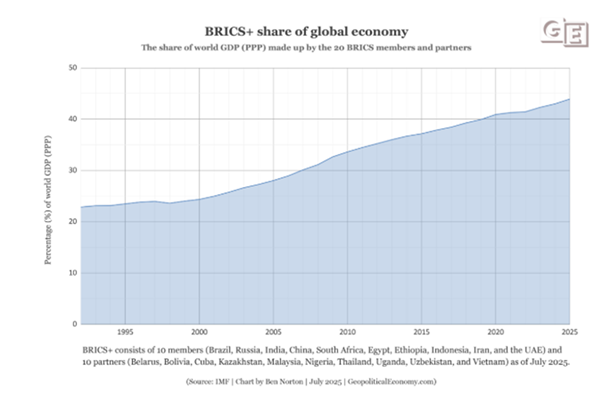

The US government’s fear of BRICS is rooted in the Global South-led organization’s increasing power. As Figure 17 shows, 20 BRICS members and partners already represent more than two-fifths of the global economy: 43.93% of world GDP, when measured at purchasing power parity (PPP). The BRICS 20 also have a combined population of 4.45 billion, meaning that they represent 55.61% of the global population — the majority of the world.

Figure 17: BRICS share of global GDP (source: IMF)

One of the key issues discussed at the 2025 BRICS summit in Brazil was de-dollarization — the attempt to create alternatives to the US dollar as the global reserve currency. Brazil’s left-wing President Lula da Silva has long been an advocate of de-dollarization. [58]

“The world needs to find a way that our trade relations don’t have to pass through the dollar,” Lula said at the BRICS summit. “Obviously, we have to be responsible about doing that carefully. Our central banks have to discuss it with central banks from other countries,” the Brazilian leader explained, according to Reuters. He added, “That’s something that happens gradually until it’s consolidated.” [60]

Lula agreed that de-dollarization is “complicated” and will be a slow, gradual process, but he maintained that it is necessary. At the 2025 BRICS summit, the Brazilian president even reiterated his call for the creation of a new global currency to challenge the US dollar. [61]

Lula declared that “BRICS is an indispensable actor in the struggle for a multipolar, less asymmetrical, and more peaceful world.” He lamented that the US-dominated international financial system benefits the rich colonial countries at the expense of the poor, formerly colonized ones.

At the BRICS summit on July 6, 2025, the 20 BRICS members and partners signed a lengthy joint statement. The Rio de Janeiro Declaration was 31 pages long and consisted of 126 points, encompassing a wide variety of subjects. The joint declaration made many references to BRICS initiatives to encourage de-dollarization. The declaration called to strengthen the BRICS bank, the New Development Bank, to “support its growing role as a robust and strategic agent of development and modernization in the Global South.” In particular, the document emphasized the need for the New Development Bank to “expand local currency financing.” [62]

Dilma Rousseff, the former Brazilian president from Lula’s left-wing Workers’ Party, has been the Chair of the New Development Bank. In her remarks at the BRICS summit, Dilma emphasized that the New Development Bank is promoting financing in local currencies. “Any business or government that borrows in foreign currency becomes subject to decisions made by the Federal Reserve or other central banks in Western developed nations,” she said, warning of exchange-rate risk and currency volatility. As a positive example of an alternative, the BRICS website noted that Dilma “pointed to a project in Brazil funded directly in renminbi, without the need for dollar conversion.” [63]

The BRICS declaration similarly urged further development of the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA), which could serve as an alternative to the US-dominated International Monetary Fund (IMF), by providing short-term liquidity to developing countries facing balance-of-payments crises.

Another initiative discussed in the declaration was the New Investment Platform (NIP), which seeks to facilitate investments in local currencies, instead of US dollars, Euro, or British pounds.

The declaration addressed the BRICS Interbank Cooperation Mechanism (ICM), which is working on “finding acceptable mechanisms of financing in local currencies.”

The joint statement also highlighted the work of the BRICS Cross-Border Payments Initiative and BRICS Payment Task Force (BPTF), which it noted identify “the potential for greater interoperability of BRICS payment systems,” as part of “efforts to facilitate fast, low-cost, more accessible, safe, efficient, and transparent cross-border payments among BRICS countries and other nations and which can support greater trade and investment flows.” [64]

As a leader of BRICS to push for de-dollarization, Brazil has deepened its bond with China. Growing ties between Brazil and China were a reality well before Donald Trump came into office. But as US president Trump tried to intervene in Brazil’s judiciary and politics and imposed one of the highest tariffs in the world, enthusiasm for collaboration between the two governments seems to be at an all-time high.

“Our ties are at their best moment in history,” China’s President Xi Jinping said in August 2025 after holding an hour-long call with Brazilian President Lula da Silva. “China supports the Brazilian people in defending their national sovereignty and also supports Brazil in safeguarding its legitimate rights and interests,” he added. Xi also told Lula that China “stands ready to work with Brazil to set an example of unity and self-reliance among major countries in the Global South.” [65]

China has been a key commercial partner for South America, and the tie with Brazil has for years been the strongest—it’s China’s top trade partner in the region and one of its main foreign investment destinations. In recent years the breadth of the relationship widened, even under former President Jair Bolsonaro, who used anti-China rhetoric and wanted to see Brazil more aligned with the United States. During Lula’s third term, the connection between China and Brazil has strengthened further.

2025 has seen significant developments. In July 2025, Brazil hosted the 17th BRICS summit, and Brazil and China co-announced the construction of a bi-oceanic railway corridor between Brazil and Peru’s Pacific coast. In addition, Chinese car maker BYD rolled out the first electric car built entirely in Brazil, at its new factory in Camaçari, Bahia, its first outside Asia. [66]

In the context of the US-China rivalry, Washington is anxious. According to US media, Brazil’s hosting the BRICS summit meeting was a factor in the Trump administration’s imposition of tariffs. On the other side of US politics, Senate Democrats recently wrote a letter to Trump saying “a trade war with Brazil would make life more expensive for Americans, harm both US and Brazilian economies, and drive Brazil closer to China.” [67]

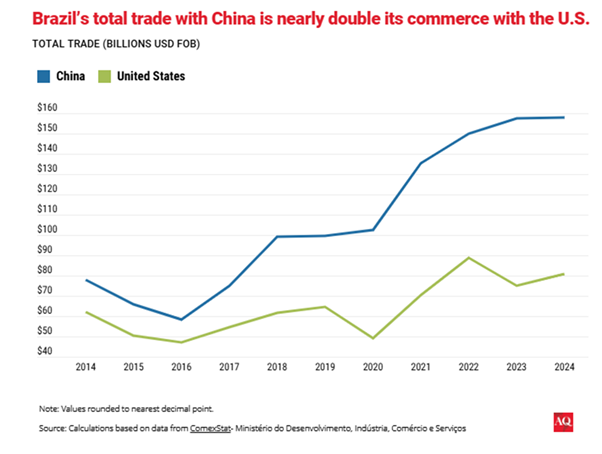

China has been Brazil’s top trading partner since 2009, when it overtook the US. As Figure 18 shows, the trade volume between Brazil and China doubled the volume between Brazil and US in 2024. China is the world’s biggest soybean importer, and gets most of its supply from Brazil. In 2024, 28% of Brazil’s exports went to China. In 2023, Brazil was China’s main supplier of soy, beef, cellulose, corn, sugar and poultry.

Figure 18: Brazil’s trade with China vs USA (source: ComexStat & Americas quarterly)

The balance of trade between Brazil and China has historically been favorable to Brazil, although China has increased its exports in recent years. And when the US tariffs took effect, China authorized 183 new Brazilian coffee companies to sell to its market, and did the same with other products. A recent new step between Brazil and China is to negotiate for the adoption of mechanisms to track the origin of agricultural products, particularly soy and beef. The goal is to create a system where both countries recognize the same environmental certifications, so that products can be tagged, for example, as “carbon-neutral beef.” There’s also talk of China importing Brazilian ethanol for the production of “sustainable aviation fuels.” [68]

Commodities comprise the vast majority of exports, but the trade relationship between Brazil and China is no longer based solely on them. The manufacturing industry represented 23% of Brazil’s exports to China in the first quarter of 2025, an increase of 6 percentage compared to the same period in 2024, according to the Brazil-China Business Council.

The kinds of exchanges have been changing, too, from government to government, to company to company, to company to client. Beyond BYD’s new factory in Camaçari, expected to be fully functional by the end of 2026, green energy and telecommunications services see strong Chinese investment, and Chinese companies operating in fields like delivery apps are expected to be active in Brazil in the coming years. [69]

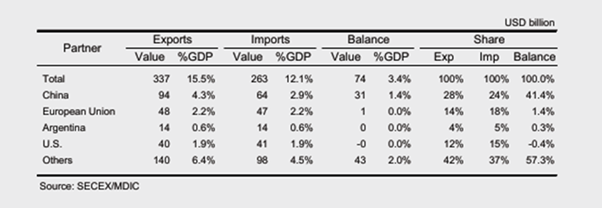

By contrast, as Table 11 shows, US-Brazil trade has been limited compared to China-Brazil trade. Brazilian exports to the US are less than 2% of Brazil’s GDP in 2024, while Brazilian exports to China are more than 4% of Brazil’s GDP. Brazil economy is too large to be bullied by the US. Moreover, Brazil’s strong ties to China guarantees Brazil’s economic independence from the US.

Table 11: Bilateral trade between Brazil and China & US, 2024(source: SECEXMDIC)

IV. Conclusion

This paper explained Brazil’s seven strengths that enabled Brazil to challenge the US as well as US President Trump. Brazil has important strategic assets such as niobium and rare earth. Brazil holds the world’s largest niobium reserves, as well as the world’s third largest rare earth reserves. Brazil also has been the world giant of agriculture that has exported the largest amount of soybean and beefs & chicken to the world. In addition, Brazil is the world’s 9th largest crude oil producer and the world’s 10th largest crude oil exporting country. Moreover, Brazil is the world’s largest producer of sugarcane ethanol, as well as the world second largest ethanol producer, leading Bazil to its energy independence. Furthermore, Brazil is a major aircraft manufacturer & exporter. Embraer, a Brazilian company, reached 3rd place in the ranking of sales of commercial aircraft, behind Airbus and Boeing in 2022. Concerning aircraft exports, Brazil ranked 7th in 2022, behind France, Germany, Canada, Spain, United States, and Ireland. And Brazil ranked 9th in the world in the aircraft/spacecraft exports. More importantly, Brazil has been a leader of BRICS that has wielded huge geopolitical influence around the world. On top of that, Brazil has strengthened its ties with China which has been another BRICS leader.

Because of these seven strengths, Brazil has not relied on the US for its economy. Rather Brazil has been able to resist US President Trump’s pressure and threats.

Brazil has been different from Mexico which depends on US for its trade and overall economy. Mexico’s total exports in 2024 were valued at US$618.98 billion, according to the United Nations COMTRADE database on international trade. Mexico’s total exports to the US in 2024 was valued at US$503.26 billion, constituting 81% of Mexico’s total exports and 27.5% of Mexico’s GDP. [70] Brazil’s exports to the US hit a record $40.3 billion in 2024, but it made up 1.9% of Brazil’s GDP in 2024. [71] Thus, Brazil sharply contrasts with Mexico in terms of its economic dependence on the US.

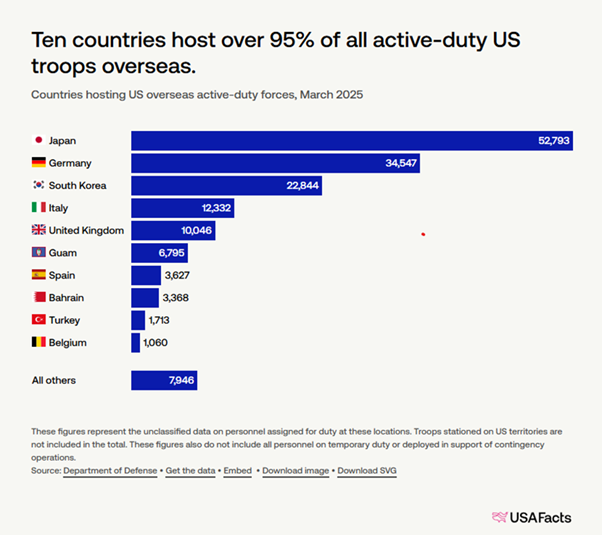

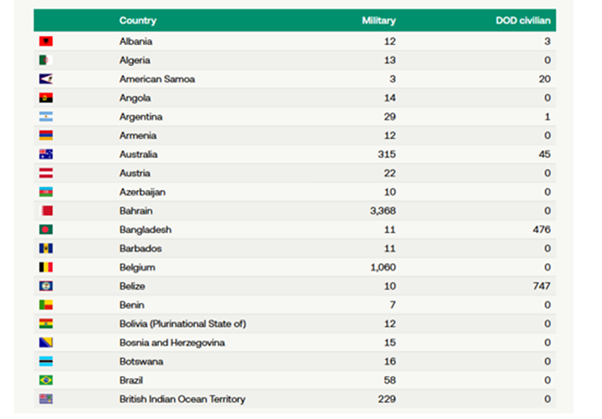

Brazil has also been different from Japan in terms of its security dependence on the US. Japan has heavily depended on the US for its security. As Figure 19 show, as of March 2025, approximately 53,000 US military servicemen have been stationed in Japan. By contrast, as Table 12 shows, there are 58 US soldiers in Brazil as of March 2025. Even 58 US servicemen in Brazil are not stationed there. They are temporarily in Brazil for a moment. Moreover, unlike Japan where there are several military bases in Japan, including major installations like Futenma air station in Okinawa and Yokota air base in Tokyo, there are no US military bases in Brazil. Thus, Brazil has not depended on the US for its security. Accordingly, Brazil sharply contrasts with Japan in terms of its security dependence on US.

Figure 19: US troops overseas (source: https://usafacts.org/articles/where-are-us-military-members-stationed-and-why/)

Table 12: Number of US military personnel (source: https://usafacts.org/articles/where-are-us-military-members-stationed-and-why/)

On the other hand, the US has a growing military presence in Australia, primarily through the marine rotational force in Darwin, which involves thousands of US marines rotating annually for training exercises. These rotations, which have happened since 2012, have grown from an initial 200 marines to nearly 2,500 each year. In addition, the US planned to host up to four nuclear-powered submarines at a future base in Australia, beginning as early as 2027. Moreover, Australia has been a member of Quad and AUKUS that are anti-Chinese alliance.

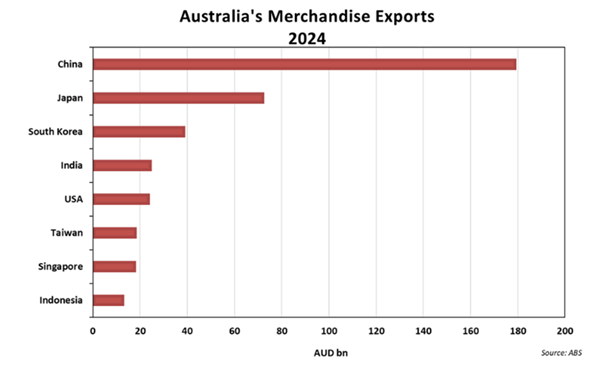

On the economic front, however, Australia exported a total $517.0 billion in merchandise goods in 2024, with $23.8billion of this going to the US. Australian goods exports to US made up 5% of its total goods exports in 2024 and were 0.9% of Australia’s annual GDP. [72] In 2024, as Figure 20 shows, around 35% of Australia’s merchandise exports by value went to China. China is also Australia’s largest export market for services with a 13.3% share. China is also Australia’s largest import partner with AUD 116 billion in 2024, followed by the US at AUD 93 billion, and Japan at AUD 32 billion. China has been Australia’s largest trading partner since 2009, when it replaced Japan. Thus, Australia is situated in-between Japan (with heavy security dependence on the US) or Mexico (with extreme economic reliance on the US) and Brazil (with economic and security freedom from the US) in terms of its economic and security dependence on US. Australia straddles a middle path between the US and China. Australia depends on China for its economy, while it strengthens its security ties with the US.

Figure 20: Australia’s exports to China, 2024 (source: Australian Bureau of Statistics)

In conclusion, Brazil’s seven strengths have made Brazil achieve both economic and security independence from the US. Thus, Brail was able to resist US pressures and threats. Even Brazil has been able to challenge the US. Brazil’s pursuit of de-dollarization and multipolar world order are good examples of such efforts.

References

[1] “Is Donald Trump trying to dial back tensions with Brazil?” Alex Kozul-Wright. 7 Oct 2025. AlJazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2025/10/7/is-donald-trump-trying-to-dial-back-tensions-with-brazil

[2] “Is Donald Trump trying to dial back tensions with Brazil?” Alex Kozul-Wright.

[3] “Is Donald Trump trying to dial back tensions with Brazil?” Alex Kozul-Wright.

[4] “Is Donald Trump trying to dial back tensions with Brazil?” Alex Kozul-Wright.

[5] For more information on Brazil, see Wikipedia.

[6] see Wikipedia

[7] For more information about income inequality in Brazil, see “Income Inequality Drops Again and Hits Lowest Level on Record in Brazil.” May.8.2025. Folha De S. Paulo.

[8] For more information, see https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/crime-rate-by-country

[9] For more information, see https://www.mbmg.mtech.edu/pdf-publications/fs23.pdf

[10] Moisés Gómez, Jinhui Li, Xianlai Zeng. “Niobium: The unseen element - A comprehensive examination of its evolution, global dynamics, and outlook.” Resources, Conservation and Recycling. Vol. 209 (October 2024), p.1

[11] Moisés Gómez, Jinhui Li, Xianlai Zeng., p. 2.

[12] For more information, see https://www.sfa-oxford.com/market-news-and-insights/niobium-swing-producer-cbmm-driving-the-future-of-advanced-materials/

[14] For more information, see https://www.sfa-oxford.com/market-news-and-insights/niobium-swing-producer-cbmm-driving-the-future-of-advanced-materials/

[16] See https://www.mining-technology.com/news/cbmm-opens-niobium-production-facility/?cf-view

[17] For more information, see https://niobiumcanada.com/why-is-niobium-a-critical-mineral-resource-for-the-united-states/

[18] https://niobiumcanada.com/why-is-niobium-a-critical-mineral-resource-for-the-united-states/

[19] “Hypersonic hegemony: niobium and the Western Hemisphere’s role in the US-China power struggle.” Guido L. Torres, Laura Delgado Lopez, Ryan C. Berg, and Henry Ziemer. CSIS. March 4, 2024.

[20] “Hypersonic hegemony: niobium and the Western Hemisphere’s role in the US-China power struggle.” Guido L. Torres, Laura Delgado Lopez, Ryan C. Berg, and Henry Ziemer.

[21] “Hypersonic hegemony: niobium and the Western Hemisphere’s role in the US-China power struggle.” Guido L. Torres, Laura Delgado Lopez, Ryan C. Berg, and Henry Ziemer.

[22] “Hypersonic hegemony: niobium and the Western Hemisphere’s role in the US-China power struggle.” Guido L. Torres, Laura Delgado Lopez, Ryan C. Berg, and Henry Ziemer.

[23] “Hypersonic hegemony: niobium and the Western Hemisphere’s role in the US-China power struggle.” Guido L. Torres, Laura Delgado Lopez, Ryan C. Berg, and Henry Ziemer.

[24] “Hypersonic hegemony: niobium and the Western Hemisphere’s role in the US-China power struggle.” Guido L. Torres, Laura Delgado Lopez, Ryan C. Berg, and Henry Ziemer.

[25] For more information, see USGS website: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2024/mcs2024-rare-earths.pdf

[27] “What are rare earth minerals, and why are they central to Trump’s trade war?” Ramishah Maruf. CNN. June 3, 2025.

[28] “What are rare earth minerals, and why are they central to Trump’s trade war?” Ramishah Maruf.

[29] “What are rare earth minerals, and why are they central to Trump’s trade war?” Ramishah Maruf.

[30] “What are rare earth minerals, and why are they central to Trump’s trade war?” Ramishah Maruf

[31] “US and Australia sign rare earths deal to counter China's dominance.” Natalie Sherman. BBC News. October 20, 2025.

[34] For more information, see https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2025/09/us-soybean-harvest-starts-with-no-sign-of-chinese-buying-as-brazil-sets-export-record.html

[38] https://soygrowers.com/news-releases/how-does-u-s-soybean-production-compare-to-brazil/

[39] https://soygrowers.com/news-releases/how-does-u-s-soybean-production-compare-to-brazil/

[40] For more information, see https://pulse.auctionsplus.com.au/aplus-news/insights/whos-got-beef-and-wheres-it-going

[41] https://pulse.auctionsplus.com.au/aplus-news/insights/whos-got-beef-and-wheres-it-going

[42] https://www.thepoultrysite.com/news/2025/08/brazil-marks-50-years-as-top-global-chicken-exporter

[43] “Top 10 exporters shipped halal meat worth $14.04 bn to OIC countries.” EuroMeat News. February 18, 2025.

[44] For more information, see https://newsroom.sialparis.com/topics/news/middle-east-food/

[45] For more information, see https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/crude-petroleum/reporter/bra

[46] D. Budny; P. Sotero (April 2007). "Brazil Institute Special Report: The Global Dynamics of Biofuels" (PDF). Brazil Institute of the Woodrow Wilson Center.

[47] The Economist, March 3–9, 2007 "Fuel for Friendship" p. 44

[48] The flourishing ethanol industry in Brazil, Brazilian Farmers.

[49] https://www.hfw.com/insights/bioenergy-series-the-evolution-of-the-brazilian-ethanol-industry/

[52] For more information, see "The Remarkable Story of Brazilian Jet Maker Embraer." Bloomberg. July 5, 2024.

[53] "Embraer Delivers 1800th E-Jet". Embraer. Archived from the original on 2 May 2024. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

[54] https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/aircraft-and-spacecraft-exports-by-country

[55] https://www.aerotime.aero/articles/largest-airlines-aircraft-manufacturers

[56] "Expansion of BRICS: A quest for greater global influence?" (PDF). Think Tank, European Parliament. 15 March 2024.

[57] For more information, see Wikipedia.

[58] https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2025/07/10/trump-threat-brics-us-dollar-western-imperialism/

[59] https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2025/07/10/trump-threat-brics-us-dollar-western-imperialism/

[60] https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2025/07/10/trump-threat-brics-us-dollar-western-imperialism/

[61] https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2025/07/10/trump-threat-brics-us-dollar-western-imperialism/

[62] https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2025/07/10/trump-threat-brics-us-dollar-western-imperialism/

[63] https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2025/07/10/trump-threat-brics-us-dollar-western-imperialism/

[64] https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2025/07/10/trump-threat-brics-us-dollar-western-imperialism/

[65] https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/brazil-deepens-bond-china/

[66] https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/brazil-deepens-bond-china/

[67] https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/brazil-deepens-bond-china/

[68] https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/brazil-deepens-bond-china/

[69] https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/brazil-deepens-bond-china/

[70] https://trading economics.com /mexico/exports-by-country

[71] https://www.publicnow.com/view/8D388094BA5934BD1B86E434070AA54216D7E628?1756817187 & SECEXMDIC

[72] See Australian Bureau of Statistics; https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/australias-trade-united-states-america

First published in :

World & New World Journal

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!