Defense & Security

Assessment of the Limitations of the EU's guarantees regarding Ukraine's security and territorial integrity

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Defense & Security

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Oct.01,2025

Oct.01, 2025

Abstract

This analysis critically examines the European Union's security guarantees for Ukraine as of 2025, amid ongoing conflict and geopolitical tensions. Despite ambitious diplomatic efforts and increased defence spending, the EU faces significant economic and military challenges that undermine its capacity to ensure Ukraine's security and territorial integrity.

Economically, the EU struggles with sluggish growth, structural inefficiencies, high public debt, and trade deficits, particularly with China, limiting resources for sustained military investment. Militarily, the EU's fragmented forces and reliance on NATO contrast sharply with Russia's extensive, war-driven military production and strategic nuclear capabilities.

The war in Ukraine demonstrates the increasing prominence of drones and missiles, areas where the EU lags behind both Ukraine and Russia in production scale and innovation. Furthermore, the shifting global order towards multipolarity and the strategic alignment of Russia and China further constrain the EU's role as a formidable security actor beyond its borders.

Key Words: EU, Ukraine, Security, Guarantees

Introduction

Russian President Vladimir Putin made a statement on September 5, 2025, warning that any foreign troops deployed to Ukraine — particularly in the context of the "coalition of the willing" led by France and the UK — would be considered legitimate targets for Russian forces. This was in direct response to a summit in Paris on September 4, where 26 countries pledged to contribute to a potential postwar security force for Ukraine, which could involve deploying troops on the ground, at sea, or in the air to deter future aggression after a ceasefire.

Putin's exact words, as reported from his appearance at the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok, included: "Therefore, if some troops appear there, especially now, during military operations, we proceed from the fact that these will be legitimate targets for destruction."[i] He further emphasised that even post-ceasefire, he saw no need for such forces if a long-term peace is achieved, adding, "If decisions are reached that lead to peace, to long-term peace, then I simply do not see any sense in their presence on the territory of Ukraine, full stop."[ii]

The "coalition of the willing" refers to a group of primarily European and Commonwealth nations, co-chaired by France and Britain, formed in early 2025 to provide security guarantees for Ukraine amid ongoing peace efforts led by US President Donald Trump. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov echoed Putin's stance, calling the presence of any foreign or NATO forces near Russia's border a threat and unacceptable.[iii]

While Putin did not explicitly name the "coalition of the willing" in his quoted remarks, the timing and context—immediately following the Paris summit announcements—make it clear his warning targets their proposed deployments.[iv]

As bold as President Putin's statement is, the EU has been making lots of noise in recent months regarding European guarantees for the future of Ukrainian security and its territorial integrity. This analysis aims to provide a "hard-eyed" assessment of the formidability of these claims, following a previous piece that analysed European diplomatic efforts to support Ukraine's territorial integrity, published here: An analysis of European Diplomatic Efforts to Support Ukraine’s Territorial Integrity. Challenges and Opportunities.

EU Economic Stance and Prospects

As of 2025, the European Union's economy remains sluggish, troubled by structural inefficiencies and mounting external pressures. Arguably, the EU bloc is increasingly uncompetitive on the global stage. Despite some stabilisation in inflation and resilient labour markets, the overall trajectory suggests a region struggling to keep pace with the United States and China, with GDP growth forecasts hovering around a dismal 1% — well below the global average of 3.2%. This underperformance is not a temporary hiccup but a symptom of deep-rooted issues, including overregulation, demographic decline, and dependency on volatile external factors.[v] Critics argue that the EU's adherence to rigid "globalist" policies, such as burdensome environmental regulations and fragmented fiscal strategies, has stifled innovation and exacerbated trade imbalances, leading to a €305.8 billion deficit with China in 2024 alone. It is pretty probable that without radical reforms, the EU risks sliding into prolonged stagnation or even collapse, as high energy costs erode competitiveness in export markets.

State of the Union (2025,10 September ) openly admits that "In the trade of goods, the EU has long had a trade deficit with China. The deficit amounted to €305.8 billion in 2024, surpassing the €297 billion deficit of 2023, but lower than the record trade deficit of €397.3 billion reached in 2022. In terms of volume, the deficit increased from 34.8 million tons in 2023 to 44.5 million tons in 2024. In the period 2015-2024, the deficit quadrupled in volume, while it doubled in value.

China is the EU's third-largest partner for exports and its biggest for imports. EU exports to China amounted to €213.3 billion, whereas EU imports from China amounted to €519 billion, indicating year-on-year decreases of 0.3% and 4.6% respectively.

In 2024, EU imports of manufactured goods accounted for 96.7% of total imports from China, with primary goods comprising just 3%. The most important manufactured goods were machinery and vehicles (55%), followed by other manufactured goods (34%), and chemicals (8%).

In 2024, EU exports of manufactured goods constituted 86.9% of total exports to China, with primary goods making up 11.5%. The most exported manufactured goods were machinery and vehicles (51%), followed by other manufactured goods (20%), and chemicals (17%).[vi]

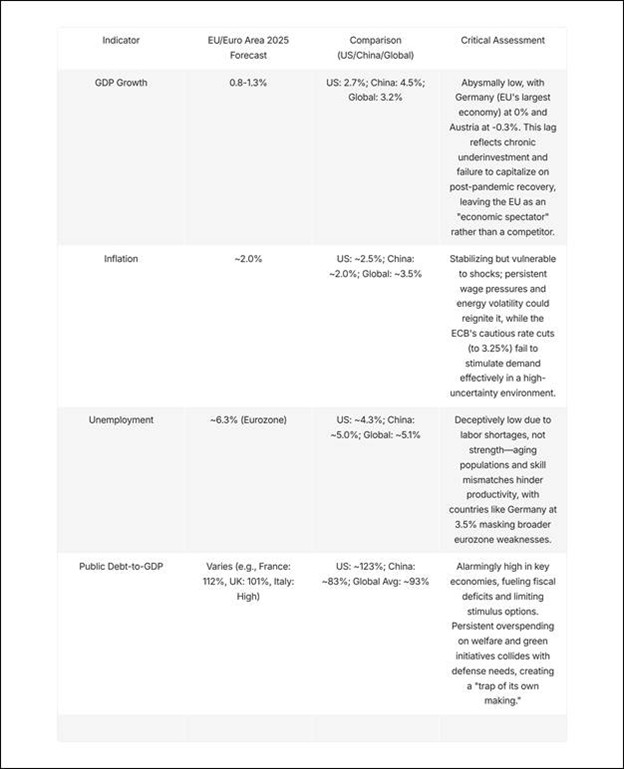

The EU's core metrics reveal an economy that is stable but uninspiring, to put it mildly, with persistent disparities across member states that undermine cohesion.

*Created by Grok – prompt: critical evaluation of the EU economic situation as of 2025.

These figures highlight internal fractures: Southern Europe (e.g., Spain at 2.6%) outperforms the core (Germany at 0%), but overall, the bloc's growth is "stuck in first gear," with services stagnant and manufacturing barely registering. Household savings are rebuilding, but consumer confidence remains low amid trade disruptions and geopolitical noise.

At its core, the EU suffers from endemic structural flaws that no amount of monetary tinkering can fix. An ageing population—projected to strain fiscal sustainability—exacerbates labour shortages and boosts welfare costs, while policies to increase participation among older workers and women remain inadequate.[vii] Productivity has lagged behind that of the US and Asia for over 15 years, hindered by fragmented regulations that impede innovation in AI and biotech.[viii] The much-touted Green Deal, while environmentally ambitious, imposes extreme costs on industries, with 44% of firms reporting trade disruptions from China (mostly dumping). Energy dependency, exposed by the Ukraine war, has led to sky-high costs that "erode competitiveness," pushing the EU toward deindustrialisation. Critics decry the EU as a "technocratic regime" where national sovereignty is eroded by Brussel’s alleged blackmail tactics, rendering parliaments mere puppets and stifling bold reforms.

The EU's economy is dangerously exposed to global headwinds, with risks tilted firmly downward.[ix] Escalating US-China trade tensions, including potential Trump-era tariffs, threaten exports (over 50% of GDP), particularly in the automotive and machinery sectors.[x] Geopolitical conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East disrupt supply chains and energy prices, while climate events add further volatility.[xi] The loss of the "peace dividend" forces a diversion of resources to defence, inflating costs and deterring investment. Capital outflows to a faster-growing US, driven by tax cuts, compound the issue, leaving Europe starved of investment. Politically, instability, such as France's government collapse over budget cuts (€44 billion), signals deeper fractures, risking social unrest and further eroding confidence.[xii]

The analysis above only scratches the surface. To have a better picture, one should also look at current and projected budget deficits and public debts. For example, according to the EU-27, the total public debt was approximately €14.2 trillion in Q1 2025.[xiii] As for budget deficits, the aggregate EU-27 deficit stood at -2.9% of GDP in Q1 2025, according to Eurostat. [xiv] Looking forward, the situation does not seem to look much better.

The prospects for public debt and budget deficits in the EU-27 over the next 5 to 10 years are characterised by gradual upward pressure on debt-to-GDP ratios due to persistent deficits, ageing populations, increased defence spending, and potential shocks like higher interest rates or geopolitical tensions. Based on the latest forecasts from the European Commission (Spring 2025), IMF (April 2025 World Economic Outlook and Fiscal Monitor), and other analyses as of September 2025, debt levels are expected to stabilise or edge higher in the short term (2025–2026), with longer-term sustainability risks emerging from megatrends like climate adaptation and demographic shifts. No comprehensive projections extend fully to 2035, but medium-term analyses (up to 2030) suggest debt could rise to 85–90% of GDP for the EU aggregate if fiscal consolidation is uneven. Deficits are projected to hover around -3% of GDP, testing the Maastricht 3% limit, with calls for prudent policies to avoid unsustainable paths.[xv]

It is against this backdrop that the SAFE investments, of which I have written here, here, here and here will have to be somehow balanced against other public policies, including immigration, education, public healthcare or housing. The picture does not look good for the EU, to put it mildly.

Current European Military Capabilities as Compared to Russia

The EU

The European Union's military and defence capabilities remain fragmented, relying on the collective forces of its 27 member states rather than a unified army. As of 2025, the EU and the UK boast approximately 1.4 million[xvi] active personnel, over 7,000 tanks, 1,300 combat aircraft, and a naval fleet including 18 submarines and multiple aircraft carriers, primarily from France and Italy. Combined defence spending has risen to approximately 2% of GDP, totalling €343 billion as of 2024, but gaps persist in strategic enablers, such as air defence, munitions, and cyber capabilities.[xvii]

The EU's strengths include industrial bases in countries such as Germany and France, which support exports and innovation in areas like drones and AI. The Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) facilitate missions, while PESCO fosters joint projects. Recent initiatives, such as the White Paper for European Defence - Readiness 2030 and the ReArm Europe Plan, aim to mobilise €800 billion for investments, including €150 billion via the SAFE loan instrument, targeting two million artillery rounds in 2025, enhanced drone systems, and military mobility.[xviii]

The EU's major weaknesses include a heavy reliance on NATO, particularly on US troops, with estimates suggesting that Europe needs an additional 300,000 soldiers and €250 billion annually to achieve independence. This includes addressing shortfalls in tanks (1,400 needed), artillery, and shells (one million for sustained combat). Challenges include political divisions, with Hungary blocking aid, and supply chain vulnerabilities amid climate threats.[xix] Overall, while progress toward a "European pillar" in NATO accelerates, achieving full strategic autonomy by 2030 hinges on member states' commitment to joint procurement and increased spending.

The Russian Federation

Russia's military capabilities in 2025 are formidable yet strained by the ongoing Ukraine war, with approximately 1.1 million active personnel, including 600,000 deployed near Ukraine.[xx] According to the US Defence Intelligence Agency, Russia's Defence spending reached 15.5 trillion roubles ($150 billion), or 7.2% of GDP, up 3.4% in real terms from 2024, funding war efforts and modernisation. Inventory includes roughly 5,000 tanks (after refurbishing Soviet stocks amid 3,000+ losses), 1,000 combat aircraft (down from pre-war due to 250 losses), and a navy with one aircraft carrier, 60 submarines, and 800 vessels total, emphasising submarine advancements.[xxi]

Russia's strengths seem to lie in strategic nuclear forces (1,550 deployed warheads, up to 2,000 non-strategic), electronic warfare, drone production (over 100 daily), and global power projection via naval deployments. Adaptations include glide bombs and unmanned systems, enabling incremental gains in Ukraine despite 750,000 - 790,000 casualties.[xxii]

According to experts, Russia's weaknesses include degraded conventional forces against NATO, stagnation in innovation, sanctions-driven dependencies on China/Iran/North Korea, labour shortages, and rising costs that hamper the development of advanced technology.[xxiii] Reforms prioritise nuclear deterrence, robotics, and force enlargement, but demographic/economic constraints may limit rebuilding over a decade. Overall, Russia sustains attrition warfare but faces sustainability challenges for broader threats.[xxiv]

The Realities of the Current Wars – the case of the war in Ukraine

The war in Ukraine is surprisingly static in a sense in which the First World War was static. We can observe numerous troops fighting a 21st-century version of a trench war, at least to an extent where the front lines seem pretty much fixed. Technological aspects of the Ukrainian war are, however, decidedly different from a hundred years ago. The war in Ukraine is marked by an extensive use of drones.

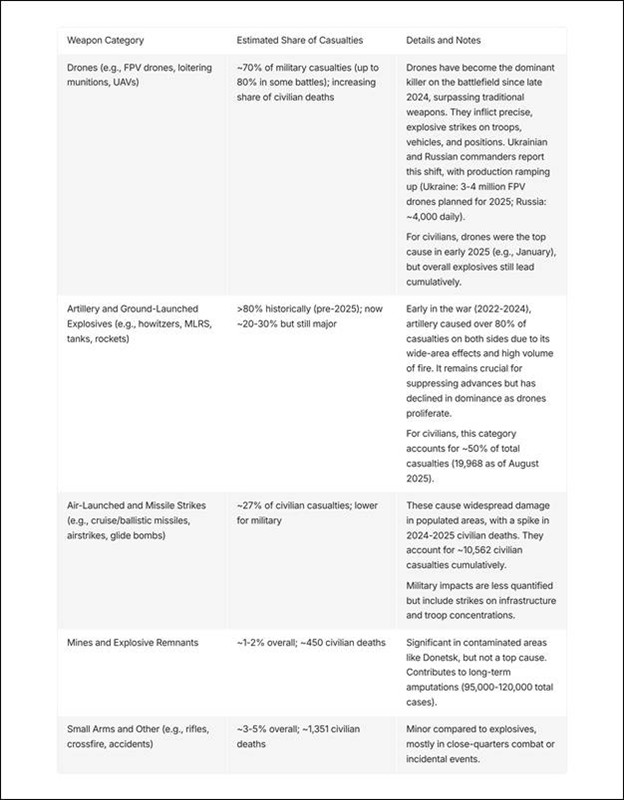

The analysis of available data from the military, UN reports, and media, up to mid-2025, indicates that the weapons causing the highest number of casualties in the Russia-Ukraine war are primarily drones and artillery systems. These two account for most of both military and civilian losses, with a notable shift toward drones in recent years. Total casualties exceed 1.2 million (primarily military, including killed and wounded), though exact figures are estimates due to underreporting and classification issues.

*Generated by Grok. Prompt: What weapons cause the most significant number of casualties in the Ukrainian war?

Multiple Sources. Please see below.[xxv]

According to publicly available data, military casualties dominate, with around 1.2 million total for Russia and Ukraine combined.[xxvi] As for civilians, the estimates indicate around 50 thousand casualties, mostly from wide-area explosives.[xxvii]

Can the EU be a Formidable Military Power of Tomorrow?

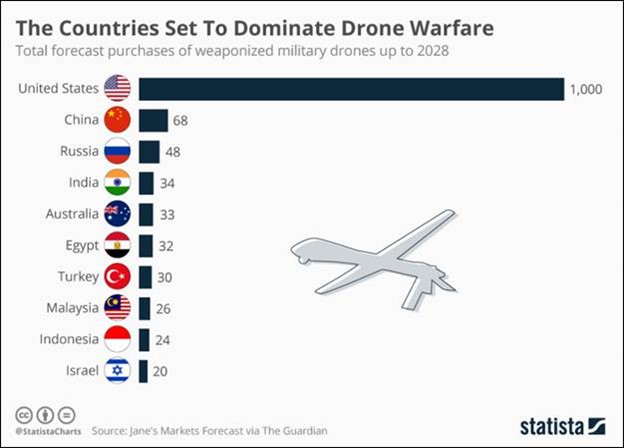

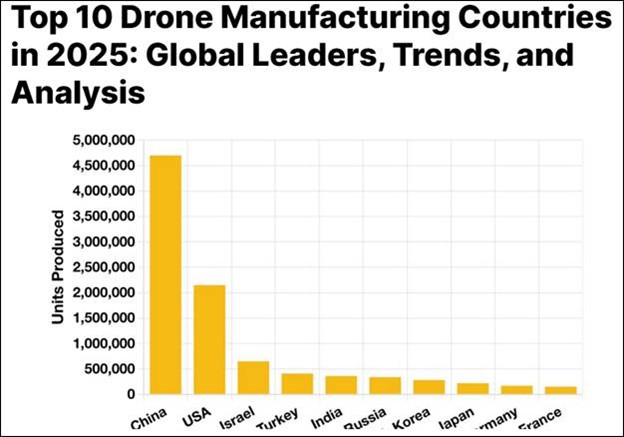

The existing intel indicates that the drones are responsible for 70 to 80% of battlefield casualties. Exact numbers are naturally difficult to come by, but experts estimate that the total usage of drones likely exceeds production slightly due to imports/donations. Having said that, the production is probably the best indicator. Consequently, the cumulative totals since 2022 exceed 10 million, with 2025 projected to add 7-9 million drones to the battlefield.[xxviii] If this trajectory continues, it means that the future wars will increasingly be fought with drones and missiles, probably operated by AI systems.

So how about the EU? The EU production is small-scale and high-value, with countries like France (Parrot SA, Thales) and Germany (Flyability) among the global top 10 manufacturers. No specific unit numbers, but the EU lags in mass production, urging scaling to millions annually for defence. The current output is likely in the tens to hundreds of thousands, primarily focused on (ISR) – Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance.[xxix]

Tellingly, "Defence Data 2024-2025" from the European Defence Agency (EDA) does not even explicitly mention drones or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). At best, the document alludes to the substantial increase in defence investment, procurement, and R&D in the EU Member States in the future, strongly suggesting that unmanned systems, including drones, are part of ongoing and future defence capability developments.[xxx]

Interestingly, it is Ukraine that outpaces the EU in its own domestic production of drones. According to the Global Drone Industry 2025 Market Report, Ukraine produced over 2 million drones domestically in 2024 and, per President Zelensky in early 2025, has the capacity to build 4 million drones annually.[xxxi] Among other interesting information, one finds:

1. The global drone market was valued at about $73 billion in 2024 and is forecast to reach $163+ billion by 2030, with a 14%+ CAGR in the latter 2020s

2. Military and defence end-use accounted for about 60% of the total drone market value in 2024.

3. DJI (Chinese producer) held an estimated 70%+ share of the global drone market by 2024.

One of the most promising developments in this respect appears to be the Eurodrone, officially known as the European Medium Altitude Long Endurance Remotely Piloted Aircraft System (MALE RPAS), a twin-turboprop unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) designed for intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and reconnaissance (ISTAR) missions. It is being developed collaboratively by Airbus (leading the project), Dassault Aviation, and Leonardo, under the management of the Organisation for Joint Armament Cooperation (OCCAR), to meet the needs of Germany, France, Italy, and Spain. The program aims to provide a sovereign European capability that's affordable, operationally relevant, and certified for flight in non-segregated airspace, thereby reducing reliance on non-European systems, such as the U.S.-made Reaper drone.[xxxii] As of 2025, it's in the development phase, with the prototype assembly underway and a maiden flight targeted for mid-2027, followed by initial deliveries around 2029-2030. As such, it is still more of a project rather than any real formidable capability.

Source: https://www.statista.com/chart/20005/total-forecast-purchases-of-weaponized-military-drones/

Apart from drones and UAVs, it is missiles that feature prominently in the modern battlefield. Here, the EU's production capabilities seem equally modest. EU production has indeed tripled overall since 2022, driven by the war. Still, it remains defensive-oriented, with slower scale-up due to component shortages (e.g., rocket motors) and a reliance on U.S. partners. Offensive long-range strike capabilities are limited, with focus on air-defence interceptors under initiatives like the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI).[xxxiii]

Key systems include U.S.-made Patriot (PAC-2 GEM-T and PAC-3 MSE) and European Aster 30 (via MBDA's Eurosam). Global Patriot production is 850 – 880 annually, but Europe receives only 400 – 500. Aster output is 190 – 225 in 2025, nearly all for Europe. Combined, EU availability is 600 – 700 interceptors per year. Under a 2:1 targeting ratio (multiple interceptors per incoming missile), this equates to defending against 235 – 299 ballistic missiles annually. Projections aim for 1,130 by 2027 and 1,470 by 2029, with licensed production in Germany (e.g., Rheinmetall).[xxxiv]

Recent analyses indicate Russia has significantly boosted its missile manufacturing since 2022, shifting to a wartime economy with 24/7 operations and foreign inputs (e.g., from North Korea and Iran). Estimates for 2025 suggest an annual output in the thousands, far outpacing pre-war levels, though exact figures are classified and reliant on external intelligence.[xxxv]

As for ballistic missiles, Russia's Production of short- and medium-range systems such as the 9M723 (Iskander-M) and Kh-47M2 (Kinzhal) has surged. Pre-war estimates pegged 9M723 at around 72 units per year, but by June 2025, this had risen to at least 720 annually, with monthly output at 60 – 70 units. Kinzhal production stands at 10 – 15 per month (120 – 180 annually). Combined, these yield 840 – 1,020 ballistic missiles per year, marking a 66% increase over the past year and a 15–40% jump in Iskander output alone during the first half of 2025.

Regarding cruise missiles, Russia's output has similarly expanded, with the Kh-101 rising from 56 pre-war to over 700 annually. Total land-attack cruise missiles (including 3M-14 Kalibr, Kh-59, and P-800 Oniks adaptations) could reach up to 2,000 per year. Stocks are estimated at 300 – 600 units currently, with projections for 5,000 by 2035.

All in all, most experts point to a significant "missile gap" favouring Russia, where its 840 – 1,020 annual ballistic missiles alone exceed the EU's defensive capacity (e.g., intercepting only 300 ballistic threats per year). Russia's total missile/drone output dwarfs EU efforts.

However, that is not all; one should also examine the usage and development of AI and AI-driven and operated military systems. This limited analysis does not allow an in-depth look into the matter. I have written about it here, claiming that the current war in Ukraine is also a huge lab for testing AI and AI-driven military systems.

Apparently, the "AI arms race" gives Russia's wartime AI applications (e.g., drone swarms) a practical edge, potentially outpacing the EU's ethical focus by 2–3 times in deployment speed. Russia's budget allocations (5–15%) exceed the EU's EDF share (4–8%), but EU venture surges (500% growth) and NATO ties provide qualitative advantages in reliable, regulated AI. Gaps include Russia's hands-on war experience versus the EU's potential lag, with calls for international law bans and more substantial EU investments to counter the risks of escalation. Optimistically, Europe's rearmament ($865 billion) could close the divide by 2030, but analysts warn of vulnerabilities without faster AI scaling.[xxxvi]

Last but not least, similar arguments can be made about the munition production capabilities. To cut a long story short, the answer to the question presented in the title of this section has to be rather negative. For example, even NATO officials, including Secretary General Mark Rutte, claimed Russia produces three times as much ammunition in three months as the whole of NATO in a year," implying 9 – 12 million annually, or even 20.5 million for a 12 times advantage. However, analysts critique these as exaggerated, noting Russia's industrial limits make figures above 4 – 6 million unfeasible without full mobilisation. External supplies bolster output: North Korea delivered ~7 million rounds by mid-2025. Russia's $1.1 trillion rearmament plan through 2036 supports long-term growth, but 2025 estimates hover at 3 – 4 million new/refurbished shells.[xxxvii]

The New World Order - Incoming!!!

Importantly, if the EU were to offer security and territorial integrity guarantees to Ukraine outside NATO, it would not face Russia alone. It would, or should I instead say will, face Russia and China cooperating and supporting each other, with other members of BRICS, remaining negatively neutral, that is, informally supporting Russia.

I suggest that, especially a European reader, carry out a little experiment. I propose that they take any map of the world that is printed in China and locate Europe. When looking at the map, the reader is advised to compare the sizes of the territories of the EU countries with those of Russia (and China combined). Apart from that the reader is advised to compare the GDP output of the EU as Against that of Russia and China, their GDP structures, the international trade vectors, structures and volumes, the number of people, natural resources (rare earths as well as gas and coal, the number and strength of TNCs (Trans-National Companies) with headquarters in Asia and Europe. In other words, carry out a simple geopolitical comparison. To say that the EU does not look impressive as compared to Russia and China is to say nothing. When carrying out such a comparison, the observer should swiftly realise that the EU is a small region in the upper left-hand corner of the map and that its relevance and importance regarding most, if not all, of the indicators mentioned above is diminishing.

The fact of the matter is that we are witnessing an absolute overhaul of the international system towards a multipolar model with the centre of gravity away from the collective west. There does not seem to be much room for Berlin, Paris or Brussels for that matter to operate as a formidable security agent outside Europe perimeter not only by the virtue of the lack of capabilities and military tools but perhaps most importantly by the lack of international recognition by the three Great powers (USA., China and Russia) and global actors such as BRICS.

References

[i] Soldatkin, V. (2025, September 5). Putin says any Western troops in Ukraine would be fair targets. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/putin-says-any-western-troops-ukraine-would-be-fair-targets-2025-09-05/

[ii] Walker, S. (2025, September 5). Western troops in Ukraine would be ‘legitimate targets’, Putin says. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/sep/05/western-troops-ukraine-legitimate-targets-vladimir-putin-says

[iii] Western troops in Ukraine would be ‘targets’ for Russian forces: Putin. (2025, September 5). Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/9/5/western-troops-in-ukraine-would-be-targets-for-russian-forces-putin

[iv] Putin says Russia would consider foreign troops deployed in Ukraine “legitimate targets.” (2025, September 5). CBS NEWS. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/russia-ukraine-war-putin-says-foreign-troops-legitimate-targets/

[v] The Conference Board Economic Forecast for the Euro Area Economy. (2025, September 5). The Conference Board. https://www.conference-board.org/publications/eur-forecast

[vi] China. EU trade relations with China. Facts, figures and latest developments. (2025, September 9). European Cmmission. https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/china_en#:~:text=Trade%20picture,%2C%20and%20chemicals%20(17%25).

[vii] A Critical Juncture amid Policy Shifts. (2025, April). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2025/04/22/world-economic-outlook-april-2025

[viii] 3 priorities to boost Europe’s competitiveness in a changing world. (2025, February 20). World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/02/europe-growth-competitiveness/

[ix] A Critical Juncture amid Policy Shifts. (2025, April). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2025/04/22/world-economic-outlook-april-2025

[x] Barkin, N. (2025, September 2). Watching China in Europe—September 2025. German Marshall Fund. https://www.gmfus.org/news/watching-china-europe-september-2025

[xi] Petersen, T. (2024, December 12). European Economic Outlook 2025: Multiple Crises Dampen the Upswing. Bertelsmann Stiftung. https://bst-europe.eu/economy-security-trade/european-economic-outlook-2025-multiple-crises-dampen-the-upswing/

[xii] Experts react: The French government has collapsed again. What does this mean for France, the EU, and Macron? (2025, September 8). Atlantic Council. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/experts-react/experts-react-the-french-government-has-collapsed-again-what-does-this-mean-for-france-the-eu-and-macron/

[xiii] Public debt at 88% of GDP in the euro area. (2025, July 21). Eurostat. https://formatresearch.com/en/2025/07/21/debito-pubblico-all88-del-pil-nellarea-euro-eurostat/

[xiv] Government finance statistics. (2025, October 21). Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Government_finance_statistics

[xv] International Monetary Fund. (2025). World economic outlook: A critical juncture amid policy shifts. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO, Europe’s debt set to surge again in new era of uncertainty, IMF warns. (2025, April 24). POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-debt-surge-uncertainty-international-monetary-fund/, Global Economy Faces Trade-Related Headwinds. (n.d.). World Bank Group. Retrieved September 13, 2025, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects , Euro Area: IMF Staff Concluding Statement of the 2025 Mission on Common Policies for Member Countries. (2025, June 19). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2025/06/18/mcs-06182025-euro-area-imf-cs-of-2025-mission-on-common-policies-for-member-countries or Stráský, J., & Giovannelli, F. (2025, July 3). OECD Economic Surveys: European Union and Euro Area 2025. OECD. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2025/07/oecd-economic-surveys-european-union-and-euro-area-2025_af6b738a/full-report/repurposing-the-eu-budget-for-new-challenges_b90b1f1d.html

[xvi] European Commission (2025, February 21). Defending Europe without the US: first estimates of what is needed. Brugel. https://www.bruegel.org/analysis/defending-europe-without-us-first-estimates-what-needed

[xvii] European Commission, EU defence in numbers. European Council, Council of the European Union. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/defence-numbers/

[xviii] European Commission, Acting on defence to protect Europeans. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://commission.europa.eu/topics/defence/future-european-defence_en

[xix] Mejino-Lopez, J., & Wolff, G. B. (2025). Boosting the European Defence Industry in a Hostile World. Interconomics, 60(1), 34–39. https://www.intereconomics.eu/contents/year/2025/number/1/article/boosting-the-european-defence-industry-in-a-hostile-world.html

[xx] Carlough, M., & Harris, B. (n.d.). Comparing the Size and Capabilities of the Russian and Ukrainian Militaries. Retrieved June 3, 2025, from https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/comparing-size-and-capabilities-russian-and-ukrainian-militaries

[xxi] Defense Intelligence Agency. (2025). 2025 worldwide threat assessment: Armed Services Subcommittee on Intelligence and Special Operations, United States House of Representatives. U.S. Department of Defense. https://www.dia.mil/Portals/110/Documents/News/2025%20Worldwide%20Threat%20Assessment.pdf

[xxii] U.S. Naval Institute Staff. (2025, May 29). Report to Congress on Russian Military Performance. USNI News. https://news.usni.org/2025/05/29/report-to-congress-on-russian-military-performance

[xxiii] Boulègue, M. (2025, July 21). Russia’s struggle to modernize its military industry. Chatham House. https://www.chathamhouse.org/about-us/our-people/mathieu-boulegue

[xxiv] Foreman, J. (2025, July 9). Military lessons identified by Russia, priorities for reform, and challenges to implementation. New Eurasian Strategies Centre. https://nestcentre.org/military-lessons/

[xxv] Adams, P. (2025, July 18). Kill Russian soldiers, win points: Is Ukraine’s new drone scheme gamifying war? BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c80p9k1r1dlo, Drones become most common cause of death for civilians in Ukraine war, UN says. (2025, February 11). Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/drones-become-most-common-cause-death-civilians-ukraine-war-un-says-2025-02-11/, Grey, S., Shiffman, J., & Martell, A. (2024, July 19). Years of miscalculations by U.S., NATO led to dire shell shortage in Ukraine. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/ukraine-crisis-artillery/, Ukraine: AOAV explosive violence data on harm to civilians. (2025, August 1). Action on Armed Violence (AOAV). https://aoav.org.uk/2025/ukraine-casualty-monitor/, Court, E. (2025, February 13). What is the death toll of Russia’s war in Ukraine? Action on Armed Violence (AOAV). https://kyivindependent.com/a-very-bloody-war-what-is-the-death-toll-of-russias-war-in-ukraine/

[xxvi] The Russia-Ukraine War Report Card, July 16, 2025. (n.d.). Harvard Kennedy School, Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs. Retrieved September 11, 2025, from https://www.russiamatters.org/news/russia-ukraine-war-report-card/russia-ukraine-war-report-card-july-16-2025

[xxvii] Number of civilian casualties in Ukraine during Russia’s invasion verified by OHCHR from February 24, 2022 to July 31, 2025. (2022, February 24). STATISTA. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1293492/ukraine-war-casualties/

[xxviii] A Perspective on Russia, Facon, S. (n.d.). A Perspective on Russia. Centre for New American Security. Retrieved September 11, 2025, from https://drones.cnas.org/reports/a-perspective-on-russia/ See also: The Russia-Ukraine Drone War: Innovation on the Frontlines and Beyond. (2025, May 28). Centre for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/russia-ukraine-drone-war-innovation-frontlines-and-beyond and Reeves, T. (2025, May 28). JUST IN: Russia Expands Drone Capabilities as Ukraine Conflict Continues. National Defence. https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2025/5/28/as-russia-ukraine-war-continues-so-does-drone-innovation

[xxix] Top 10 Drone Manufacturing Countries in 2025: Global Leaders, Trends, and Analysis. (2025, July 19). QUASA. https://quasa.io/media/top-10-drone-manufacturing-countries-in-2025-global-leaders-trends-and-analysis

[xxx] European Defence Agency. (2025). Defence Data 2024-2025. European Defence Agency. https://www.eda.europa.eu

[xxxi] Global Drone Industry: 2025 Market Report. (2025, July 16). Tech Space 2.0. https://ts2.tech/en/global-drone-industry-2025-market-report/

[xxxii] Global Drone Industry: 2025 Market Report. (n.d.). EUROPEAN MEDIUM ALTITUDE LONG ENDURANCE REMOTELY PILOTED AIRCRAFT SYSTEMS – MALE RPAS (EURODRONE). Retrieved September 15, 2025, from https://www.pesco.europa.eu/project/european-medium-altitude-long-endurance-remotely-piloted-aircraft-systems-male-rpas-eurodrone/

[xxxiii] Casimiro, C. (2025, August 14). European Defense Production Triples Since Russia-Ukraine War: Report. WAR ON THE ROCKS. https://thedefensepost.com/2025/08/14/european-defense-production-tripled/

[xxxiv] Hoffmann, F. (2025, July 6). Europe’s Missile Gap: How Russia Outcompetes Europe in the Conventional Missile Domain. MIssile Matters - with Fabian Hoffmann. https://missilematters.substack.com/p/europes-missile-gap-how-russia-outcompetes

[xxxv] Hoffmann, F. (2025, September 8). Denial Won’t Do: Europe Needs a Punishment-Based Conventional Counterstrike Strategy. WAR ON THE ROCKS. https://warontherocks.com/2025/09/denial-wont-do-europe-needs-a-punishment-based-conventional-counterstrike-strategy/

[xxxvi] Zysk, K. (2023, November 20). Struggling, Not Crumbling: Russian Defence AI in a Time of War. Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/struggling-not-crumbling-russian-defence-ai-time-war and Cohen, J. (2025, June 30). The Future of European Defense. Goldman Sachs. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/the-future-of-european-defense

[xxxvii] Lehalau, Y. (2025, July 25). Is Russia Outpacing NATO In Weapons Production? Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty. https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-nato-weapons-production-us-germany/33482927.html

First published in :

World & New World Journal

Dr. Śliwiński Krzysztof, Feliks is an Associate Professor at the Department of Government and International Studies of Hong Kong Baptist University (https://gis.hkbu.edu.hk/people/prof-krzysztof-sliwinski.html) and Jean Monnet Chair.

He received his doctorate from the University of Warsaw's Institute of International Relations in 2005. Since 2008, he has been employed at Hong Kong Baptist University. He has regularly lectured on European Integration, International Security, International Relations, and Global Studies. His primary research interests include British Foreign Policy and Security Strategy, Polish Foreign Policy and Security Strategy, Security and Strategic Studies, Traditional and Non-traditional Security Issues, Artificial Intelligence and International Relations, European Politics and the European Union, Theories of European Integration, Geopolitics and Teaching and Learning.

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!