Energy & Economics

Life of youth in sanctioned Russia: VPN, rebranding and copycats

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Energy & Economics

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Oct.27,2025

Oct.27, 2025

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia underwent severe economic, political, and cultural changes. Previously blocked by the iron curtain, Russians suddenly found themselves exposed to Western influence. In the early 2000s’, Russia was culturally and economically thriving. Nowadays, it is hard to imagine controversial artists such as drag artists, t.A.T.u. and others performing on the national stage, when back then all of this was broadcast across the country. For citizens of border cities such as Saint Petersburg and Kaliningrad, this was a period of frequent travelling abroad. Trips to neighboring countries to buy products or visit relatives have become part of normal life. Russia seemed more democratic, integrated, and culturally alive. The 2010s’ marked the beginning of sanctions. Yet for most Russians, daily life hardly changed. Even after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, people continued to travel, buy “sanctioned” goods, and enjoy global events. Russia even hosted the FIFA World Cup in 2018, which was a moment of international recognition that contrasted with the West’s growing political distance.

This changed drastically in 2022, when Moscow launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. This time, the sanctions were sweeping and deeply felt in everyday life. Major international companies announced their departure from the Russian market. According to Russian claims, U.S. companies lost more than $300 billion as a result, while the Financial Times reported that European firms lost over $100 billion in just 18 months. It has now been more than three years since major international brands officially “left” Russia. McDonald’s, Adidas, Zara, IKEA, and many others appeared to vanish from Russian market. On paper, they exited what many call a rogue state. In reality, most of them never truly left.

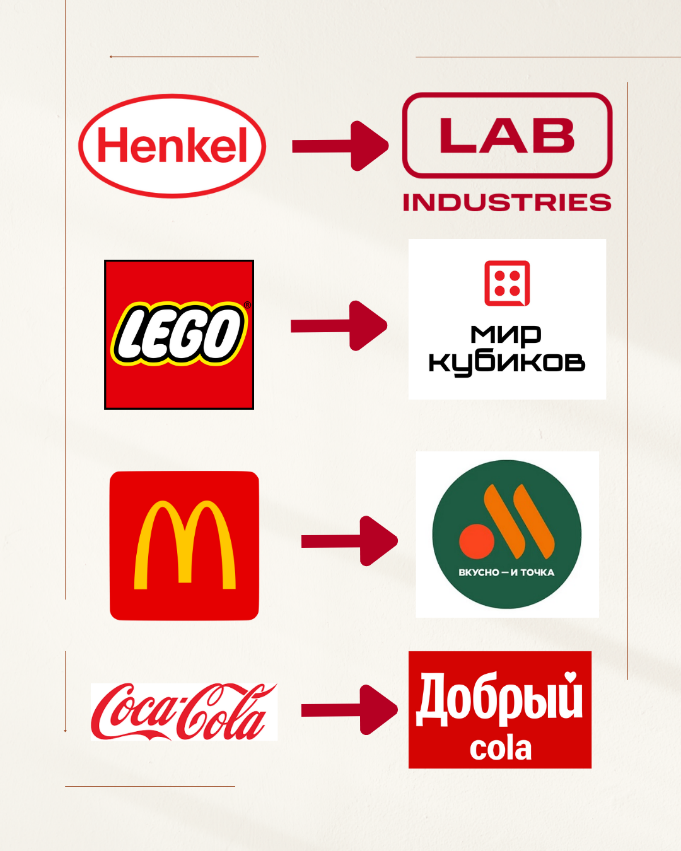

By early 2023, Russia’s consumer market was full of “new-old” brands. While some companies left outright, the majority transferred stocks to local managers, often at discounts of up to 70%. As a result, there was a strange marketplace with familiar stores but unfamiliar names. At the same time, Ukrainian observers note a different reality. Forbes reported that many foreign revenue leaders in Russia, including Philip Morris, Pepsi, Mars, Nestlé, Leroy Merlin, and Raiffeisen Bank never left Russia at all. According to B4Ukraine, these companies together paid over $41.6 billion in taxes, equivalent to roughly one-third of Russia’s annual military budget. Back in 2023 Philip Morris International confirmed that it would “rather keep” its Russian holdings than sell them at a discount to local investors. For example, L’Occitane simply transliterated its name into Cyrillic, while Spanish corporation Inditex sold its stocks to Daher, and brands like ZARA, Pull&Bear, Bershka were replaced by alternative brands like Maag, Ecru, Dub. Thus, authentic ZARA’s clothing still can be easily found on internet marketplaces, such as Lamoda. Food and beverage: Starbucks transformed into Stars Coffee, McDonald’s into Vkusno i Tochka. Coca-Cola was sold to a Russian businessman and rebranded as Dobryi Cola. Yet, many shops still sell original Coca-Cola imported from neighboring countries such as Belarus, Kazakhstan, or Poland. Finnish company Fazer Group sold Khlebniy Dom (major bread and pastry company) to “Kolomenskyi” holding, keeping the same legal structure, representatives, and recipes. Consumer goods and toys: Lego returned as Mir Kubikov (“Cubic World”), offering identical products under a new name. German holding Henkel became Lab Industries, selling the same products under Cyrillic labels.

Earlier this year Daher Group claimed that Adidas would reopen stores by November 2025, though details remain unclear. Nike, meanwhile, continues to operate in Russia under the abbreviation NSP — Nike Sport Point. For Russian youth, these “copycat” and alternative have a mixed reaction. On social media platforms like Telegram, Instagram and TikTok memes mocking the awkward logos and uninspired renamings were circulating. Young consumers still crave original products, especially iPhones, brand clothes and cosmetics, which are often purchased through parallel imports, friends, albeit at inflated prices. Polls confirm such trend. According to the Russian Public Opinion Research Center (RPORC), 94% of Russians believe that Western brands will eventually return, and 68% think it is only a matter of time. About 60% of the population continues to buy sanctioned goods; for 28%, it has become a habit. Two-thirds of respondents say they would prefer national brands only if the price were equal. This dual reality for young Russians means living in a consumer world that is both familiar and fractured.

Despite adaptation, Russia’s economic outlook remains mixed. Polling by RPORC suggests that while many Russians believe the economy is worsening, a growing number also describe it as “stabilizing.” As RPORC explained: “Businesses and people were able to adapt to new conditions. Not everyone succeeded, but economic catastrophe did not happen.”

The Levada Center found similar resilience. Half of respondents said their lives had not changed in recent years, or that they had even found new opportunities. One in five, however, admitted to abandoning their old lifestyle or struggling to adapt. Two-thirds reported feeling confident about the future, most of them relying on wages and pensions, with fewer depending on savings or secondary income. Economic indicators, however, tell a more fragile story. The Consumer Sentiment Index fell to 110 points in August 2025, down from 117 in June. Assessments of current living conditions dropped sharply, while expectations for the future also declined. Businesses face ongoing challenges. According to the Bank of Russia’s September monitoring, companies reported weaker demand, especially in manufacturing, alongside persistent cost pressures from labor shortages and rising expenses. Inflation has moderated to 8.2% year-on-year, but expectations of higher prices remain. In response, the central bank cautiously lowered its interest rate from 18% to 17%. While this move was intended to encourage funding and investment, it came with warnings. High rates had already limited capital investment and strained both households and firms. For younger Russians, this translates into expensive loans, delayed purchases of homes or cars, and fewer stable jobs. Small firms are especially vulnerable, and larger companies hesitate to commit to long-term investment in Russia. The October 24 monetary policy meeting is expected to clarify whether further rate cuts will follow, but for now, the message remains one of “cautious easing amid a fragile economy.” For Russian youth entering the workforce, the environment is uncertain. Jobs in international firms are disappearing, wages struggle to keep pace with inflation, and credit is harder to access. Their career paths are increasingly shaped by state-owned companies or sanctioned industries rather than by global opportunities.

Sanctions are only half the story. Alongside them, the Russian government has tightened internal restrictions, from healthcare to social media, touching nearly every aspect of citizens’ lives. On September 1, 2025, a wave of new restrictions and laws came into force. In healthcare, paramedics and obstetric nurses were legally authorized to provide emergency care in the absence of doctors, while health and dietary supplements (“БАДы”) became subject to stricter regulation. Additionally, a new federal list of Strategically Significant Medicinal Products was introduced to encourage full domestic production of essential drugs. This move aims to reduce Russia’s dependence on imported medicine and support local firms. Beyond healthcare, other laws targeted digital life and education. Advertising VPNs was banned, along with advertising in prohibited apps. While internet users faced growing difficulties with messaging platforms, the government launched a new app called Max, a Russian equivalent of China’s WeChat, while simultaneously restricting access to competitors such as Telegram, WhatsApp, and Viber. Although text communication remains possible, audio and video calls are increasingly blocked. According to the Levada Center, 71% of Russians recently reported problems accessing the internet on mobile phones, and 63% experienced issues with messaging apps. Public opinion is split: 49% support Roskomnadzor’s decision to block voice calls on WhatsApp and Telegram, while 41% oppose it. Support varies by age and education level: younger people and the highly educated are far more likely to oppose restrictions, disapprove of Putin’s presidency, and favor a ceasefire in Ukraine. Education has also come under tighter state control. New quotas for universities, stricter graduation requirements, and the exit from the Bologna education system are expected to make it harder to pursue higher education abroad. For Russian youth, this means growing up in a system where schools and universities serve not only as centers of learning but also as instruments of political loyalty.

Older generations of Russians remember both the Iron Curtain and the sudden openness of the 2000s. Today’s youth, Gen Z and Gen Alpha, are growing up in a very different environment. Born into a Russia that once promised travel, global brands, and open media, they now face a country of copycat stores, patriotic lessons, and state-controlled apps. Their world is paradoxical: connected through VPNs, Telegram, and imported iPhones, yet isolated by censorship, propaganda, and restricted travel. They can mock “Vkusno i Tochka” on Telegram but cannot easily study abroad or see global TikTok trends without additional tools. This contradiction defines Russian youth today. They adapt quickly to new changes and even mock fake brands, find ways around bans, and stay tuned to global culture. But they are also growing up in a system that narrows horizons, imposes loyalty, and tries to shape them into a generation of compliance. Thus, the question remains. Will sanctions and state policies succeed in creating a more conservative, obedient generation? Or will Russian youth continue to find creative ways to remain connected to the wider world? Their choices will shape not only the future of Russian consumer culture, but the political and cultural direction of the country itself.

https://www.vedomosti.ru/business/articles/2025/02/18/1092830-amerikanskii-biznes-poteryal https://b4ukraine.org/what-we-do/corporate-enablers-of-russias-war-report https://www.ft.com/content/656714b0-2e93-467b-92d6-a2d834bc0e2b

First published in :

World & New World Journal

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!