Defense & Security

Why Sunni Arab countries in the Middle East oppose US military strikes against Iran?

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Defense & Security

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Feb.16,2026

Feb.16, 2026

In late December 2025, mass protests erupted across Iran, driven by public anger over the deepening economic crisis. Initially led by bazaar merchants and shopkeepers in Tehran, the demonstrations quickly spread to universities and major cities such as Isfahan, Shiraz, and Mashhad, becoming the largest unrest since the 2022 Mahsa Amini protests. Over time, the movement expanded beyond economic demands to include calls for freedom and, in some cases, the overthrow of the regime. Protesters chanted anti-government slogans such as “Death to the Dictator”. [1] In response, since late December 2025 Iranian state security forces have engaged in massacres of dissidents. The Iranian government has also cut off internet access and telephone services in an attempt to prevent protesters from organizing. The Iranian government has accused the United States and Israel of fueling the protests, which analysts suggest may be a tactic to increase security forces’ willingness to kill protesters. A Sunday Times report, based on information from doctors in Iran, said more than 16,500 people were killed and more than 330,000 injured during the unrest. The Interior Ministry in Iran verified 3,117 people had been killed in protests. [2] The Iranian protests, the largest in the Islamic republic’s 46-year history, appear to have subsided for now in the face of a violent government crackdown. US President Donald Trump has threatened to “hit very hard” if the situation in Iran escalates, reigniting concerns about possible American intervention in the region. Even Trump called Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei “sick man” in an interview with Politico on January 17th, 2026, and said, “It’s time to look for new leadership in Iran.” It appeared to be the first time Trump had called for the end of Khamenei’s rule in Iran. [3] Despite having repeatedly threatened to attack Iran if the regime were to start killing protesters, Trump has held off on any immediate military action against the Islamic Republic. While the US reportedly sent the USS Abraham Lincoln carrier strike group to the Middle East on January 15th, 2026, President Trump has not specified what he might do. However, on January 28th, 2026, Trump posted on social media: “A massive Armada is heading to Iran... It is a larger fleet, headed by the great Aircraft Carrier Abraham Lincoln, than that sent to Venezuela. Like with Venezuela, it is, ready, willing, and able to rapidly fulfill its mission, with speed and violence, if necessary.” Saying that time is running out, Trump demanded that Iran immediately negotiate a nuclear deal. He also suggested his country’s next attack on Iran could be worse than last year’s. However, US allies in the Gulf are known to oppose such US attacks on Iran. On January 14th, 2026, the New York Times’s headline “Trump’s Gulf allies don’t want him to bomb Iran” caught people’s attention. Earlier, The Wall Street Journal also reported the previous day that Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Oman are lobbying the Trump administration against attacking Iran. Those Sunni Muslim countries have long felt threatened by Shiite Iran. Particularly, Saudi Arabia is the leading country of Sunni Islam and has long competed with Iran, the leading nation of Shia Islam, for regional dominance in the Middle East. Then a question arises: Why Sunni Arab countries, which do not feel favorable toward Iran, oppose US military strikes against Iran? This paper deals with this puzzle. It first explains the relationship between Shiite Iran and Suni Arab countries and then examines why Suni Arab countries are against US military strikes on Shiite Iran.

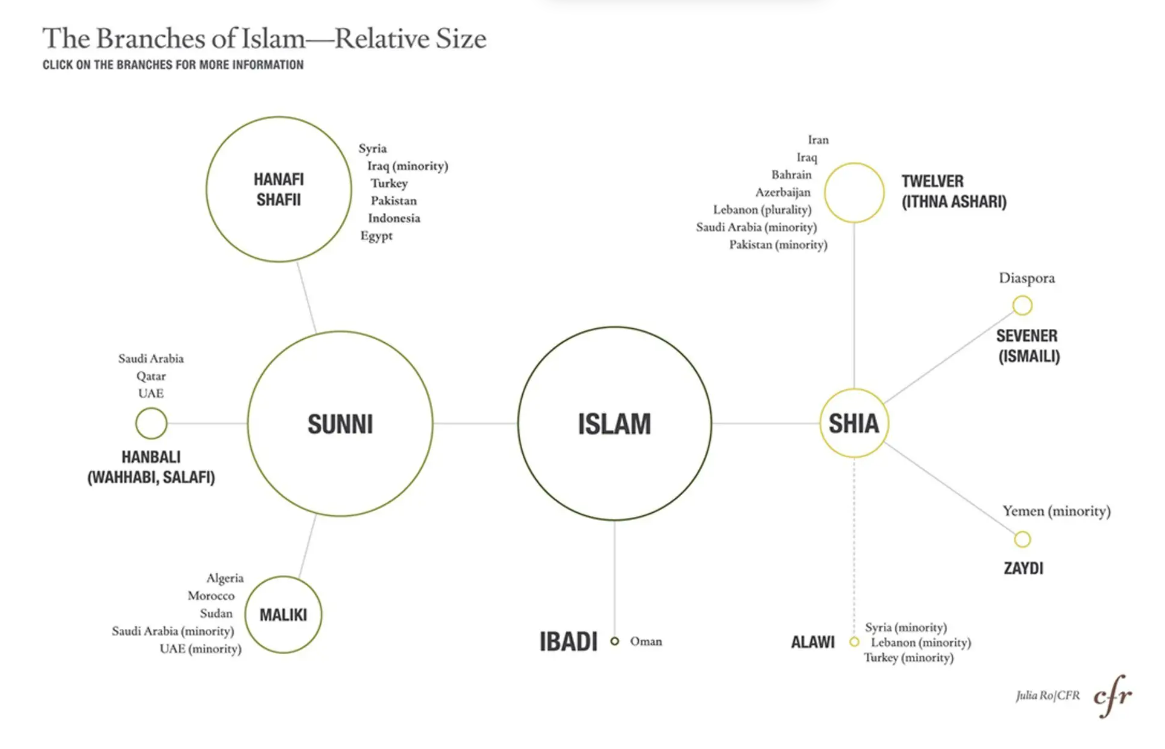

Sunni and Shia Muslims have lived peacefully together for centuries. In many countries it has become common for members of the two sects to intermarry and pray at the same mosques. They share faith in the Quran and the Prophet Mohammed’s sayings and perform similar prayers, although they differ in rituals and interpretation of Islamic law. Shia identity is rooted in victimhood over the killing of Husayn, the Prophet Mohammed’s grandson, in the seventh century, and a long history of marginalization by the Islam’s dominant sect of Sunni majority, As Figure 1 shows, the Sunni majority, which approximately make up 85 percent of the world’s 1.6 billion Muslims, viewed Shia Islam with suspicion, and extremist Sunnis have portrayed Shias as heretics and apostates.

Iran’s Islamic Revolution in 1979 gave Shia cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini the opportunity to implement his vision for an Islamic government ruled by the “guardianship of the jurist”, a controversial concept among Shia scholars that is opposed by Sunnis, who have historically differentiated between religious scholarship and political leadership. Shia ayatollahs have always been the guardians of the faith. Khomeini claimed that clerics had to rule to properly perform their function: implementing Islam as God intended, through the mandate of the Shia Imams. [4] Under Khomeini, Iran began an experiment in Islamic rule. Khomeini tried to inspire further Islamic revival, preaching Muslim unity, but supported armed groups in Lebanon, Iraq, Bahrain, Afghanistan, and Pakistan that had specific Shia agendas. Sunni Islamists, such as the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas, admired Khomeini’s success, but they did not accept his leadership, underscoring the depth of sectarian suspicions. The relationship between Shia Iran and Sunni Arab countries is largely defined by geopolitical rivalry and sectarian competition, primarily between Iran and Saudi Arabia, playing out in proxy conflicts (Syria, Lebanon, Yemen, and Iraq) and political influence, fueled by the 1979 Iranian Revolution and historical Sunni-Shia Islamic differences. This rivalry exploits religious narratives to gain regional hegemony, supporting opposing sides in regional conflicts and influencing domestic politics in countries such as Syria, Yemen, and Bahrain. For example, Saudi Arabia and Iran have deployed considerable resources to proxy battles, particularly in Syria, where the stakes are highest. Saudi Arabia closely monitors potential restlessness in its oil-rich eastern provinces, home to its Shia minority, and deployed its military forces, along with other Gulf countries, to suppress a largely Shia uprising in Bahrain. It also assembled a coalition of ten Sunni countries, backed by the US, to fight Shia Houthi rebels in Yemen. The war, fought mostly from the air, has exacted a high civilian toll. Saudi Arabia had provided hundreds of millions of dollars in financial support to the predominantly Sunni rebels in Syria, while Iran had allocated billions of dollars in aid and loans to prop up Shia Assad government in Syria and had trained and equipped Shia militants from Lebanon, Iraq, and Afghanistan to fight in Syria. [5] The relationship between Shia Iran and Sunni Arab countries is summarized as follows: A. Key players of Shia and Sunni Muslim world are as follows : Iran (Shia): As a Shia-majority theocracy, Iran seeks regional influence. Saudi Arabia (Sunni): As a key US ally and the leading Sunni nation, Saudi Arabia promotes Wahhabism. Other Sunni nations: Egypt, UAE, and Jordan generally align with Saudi Arabia against Iran. B. Key drivers of tensions between Shia Iran and Sunni Arab countries are below: Geopolitical struggle for dominance: Both Iran and Saudi Arabia vie for leadership in the Middle East, seeing the other as a main threat. Religious divide (Sunni vs Shia): Iran’s Shia theocracy challenges Sunni-led countries, in particular Saudi Arabia, which sees itself as the leader of the Sunni Muslim world. The Iranian Revolution in 1979: The Iranian revolution created a revolutionary Shia nation, alarming conservative Sunni monarchies and intensifying regional power struggles. C. The rivalry is expressed as follows: Proxy wars: Iran supports Shia military groups (e.g., Houthis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon), while Saudi Arabia backs Sunni factions and governments, leading to conflicts in Yemen, Syria, and Iraq. Sectarian polarization: Both Iran and Saudi Arabia use sectarian narratives to mobilize support, while Saudi Arabia marginalizes Shia minorities in Sunni countries and exacerbates internal conflicts. Regional alliances: Sunni countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain, facing a mutual threat from Iran, have increasingly normalized ties with Israel by signing the Abraham Accords for regional security.

Sunni Muslim countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, oppose US military strikes against Iran due to fear of potential retaliatory attacks on their own soil by Iran and economic fallout & disruption, regional instability, and concerns about expanding Israeli influence. Despite geopolitical rivalry between Shia Iran and Sunni Arab countries, these Sunni countries prioritize national security, avoiding a full-scale conflict that could devastate the Gulf region.

1. The first reason why Sunni Arab countries oppose US military strikes on Iran is that they worry about potential retaliatory attacks on their own soil by Iran and economic fallout & disruption. A. Fear of RetaliationSunni-majority nations fear that if the US attacks Iran, Iran will retaliate against them, damaging critical oil infrastructure and causing economic devastation. The Gulf states’ primary short-term concern is a potential Iranian retaliation targeting strategic infrastructure on their territory, including symbols of governance, oil and gas production facilities, desalination plants, and military bases, in particular those hosting US forces. Another major concern is Iranian action to disrupt shipping lines near the Strait of Hormuz, through which approximately a quarter of global oil and gas traffic passes. [6] In addition, any harm to Iran would also affect the economies of the Gulf states that maintain trade relations with it, particularly the United Arab Emirates, Iran’s principal trading partner in the Middle East. The Iranian strike on Qatar in June 2025 was a reminder of the vulnerability of infrastructure in the Gulf, even though Iran reportedly provided advance warning. Indeed, reports indicated that Iran conveyed messages to its Gulf neighbors urging them to persuade the US to refrain from attacking Iran, while warning that such an attack would trigger retaliation against military bases on their territory. Moreover, Iran could also activate its regional proxies - by putting pressure on the Houthis not only to target Israel but also to renew disruptions to freedom of navigation in the Red Sea and potentially even carry out strikes on the Gulf states themselves. [7] Unlike Israel, the Gulf states are geographically very close to Iran and have more limited military capabilities. Most of their population, economy, and infrastructure are concentrated along narrow coastal strips exposed to the Gulf shoreline. They experienced firsthand Iran’s drone and missile attack on Saudi Aramco oil facilities in 2019 and learn a simple lesson: Even a “limited” Iranian attack can be devastating. In line with this threat perception, several Gulf states reportedly are acting to prevent a US military strike on Iran through mediation and facilitation. [8] The Gulf states oppose a US strike on Iran not because they believe such a move is unjustified in principle but rather because they are convinced that they would bear the immediate cost. Their opposition may also reflect the concern that the attack plans would not, in their view, produce the desired results. Accordingly, behind the scenes, Saudi Arabia, together with Qatar and Oman, has led quiet efforts to persuade the US to avoid military intervention, warning that regime collapse or military escalation would shake oil markets and endanger their stability. Reports indicate that Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Oman have focused on preventing the use of escalatory rhetoric and military steps that could lead to miscalculation and escalation. Strikes against the Gulf states using drones, missiles, maritime sabotage, or regional proxies are readily available and familiar options for Iran. For the Gulf states, an Iran-US confrontation constitutes a direct threat to their internal, economic, and security stability. Mediation, therefore, is a defensive tool from their perspective - an attempt to keep the battlefield away from Gulf territory, even if this does not resolve the root causes of the confrontation. It is also possible that reports about efforts to prevent a US strike are intended to allow time to improve defensive preparedness with US assistance, particularly against missile attacks. In any case, the image of the Gulf states as opposing a strike against Iran and seeking to prevent it serves their interest in reducing tensions between themselves and Iran.

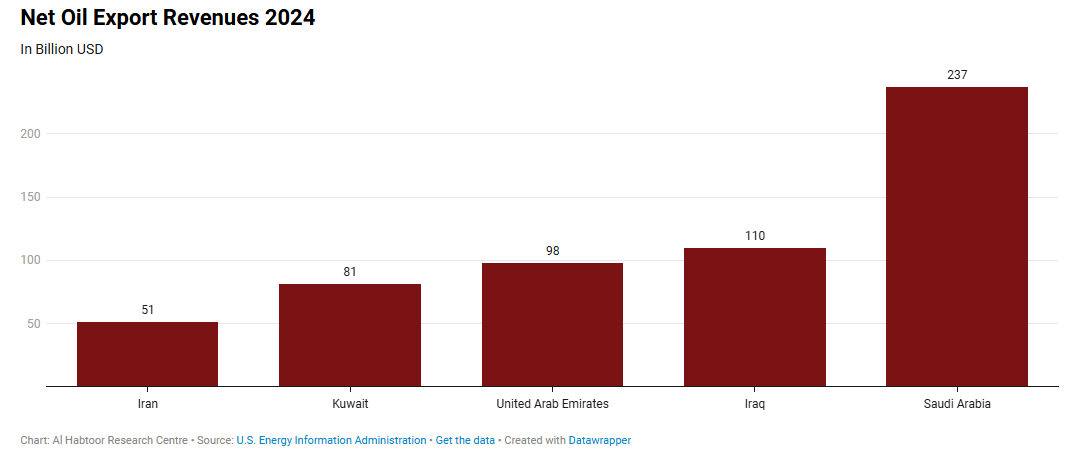

B. Economic fallout & disruptionA violent confrontation between Iran and the Gulf states could prompt serious economic consequences. “If Iran decides to block trade routes, for example, this would have a significant effect on the economies of the Gulf states,” Pauline Raabe from the Middle East Minds think tank in Berlin said. [9] Iran could block passage in the Persian Gulf by closing the Strait of Hormuz. “We have already seen what this means to international shipping when the Houthi rebels, a proxy group of Iran, fired on vessels in the Red Sea,” she explained, referring to the attacks on shipping in what the Houthis claimed was in support of Hamas in Gaza. Such a development in the Persian Gulf would, of course, have enormous economic consequences “first for the Arab countries, but then for the global economy as a whole,” Raabe said. An economic shock wave with catastrophic global implications would have immediate impacts on the temporary or prolonged closure of the Strait of Hormuz, with global energy markets suffering the most from such repercussions, triggering a significant disruption in international gas and oil supplies worldwide. The economic damage would be especially significant for regional economies. As Figure 2 shows, the Gulf countries, whose economies heavily depend on gas and oil exports, would experience an immediate and significant decline in their main sources of income. As Figure 2 shows, in 2024, Saudi Arabia earned $237 billion in oil export revenue, while Iraq earned $110 billion, and the United Arab Emirates $98 billion.

Widespread economic contraction and hardship, severe budget deficits, and currency devaluations would be some of the immediate consequences of these revenue declines, potentially triggering widespread political and social instability. Ironically, Iran, the country most likely to consider such a closure of the Strait of Hormuz, would also suffer severe economic repercussions. As Figure 2 shows, in 2024, Iran earned $51 billion in oil export revenue. Its oil revenues, which are vital and driving forces for its fragile and struggling economy, would be halted, and its ability to import necessary goods, such as food and refined petroleum products, would be significantly restricted, thereby causing further instability for its regime. The top priority for the Arab Gulf states, without a doubt, is the uninterrupted export of their oil without the closure of the Strait of Hormuz or attacks on shipping in the Persian Gulf. Data from Kpler and Vortexa show that in recent months, Iran has accumulated about 166 million barrels of floating storage near Chinese waters. Even if Iran’s oil loadings were disrupted for a while, this stockpile could sustain sales to China for three to four months. By contrast, the closure of the Strait of Hormuz or any attack on tankers in the Persian Gulf would be extremely damaging for Arab producers, particularly because Saudi Arabia and the UAE, even with alternative pipelines, can protect only about half of their export volumes, while Qatar, Iraq, Kuwait, and Bahrain have no alternative export routes. Eckart Woertz, director of the German Institute of International and Security Affairs in Hamburg, also notes that the Gulf nations are keen to avoid any disruptions as they are currently focused on their economic transformation processes. “Saudi Arabia wants to reposition itself economically with its ‘Vision 2030’ and any unrest would be a major hindrance,” he told DW, a German television network. This also applies to more traditional industries, such as the extraction of natural resources, especially oil. “Any uncertainty is detrimental to these industries, as they depend on trust and functioning supply chains. Both are prerequisites for the economy in the Gulf states,” Woertz said. [10]

2. The second reason why Sunni Arab countries oppose US military strikes on Iran is that they worry about regional instability and insecurity caused by US military strikes. A. Regional instability and insecurity:There is a strong preference for diplomatic solutions to avoid a chaotic, uncontrollable conflict that could engulf the entire Middle East. Just as an Iranian strike against targets in the Gulf states constitutes a tangible threat, the Gulf states also fear that a US campaign in Iran could precipitate a rapid collapse of the regime in Tehran. They do not view the swift fall of the Islamic Republic as a desirable outcome as it could trigger widespread instability, including succession struggles within Iran, the disintegration of governing institutions, the empowerment of extremist actors, potential waves of refugees, and, above all, the loss of a clear address for crisis management. Dr Karim Emile Bitar, a lecturer in Middle East Studies at Sciences Po Paris noted that the Saudi leadership is particularly apprehensive about chaos and fragmentation in Iran, whether from a sudden collapse of the Iranian Islamic Republic or US-led war-induced regime change. Officials in Saudi Arabia are especially concerned about domestic security, including the potential for unrest among Shia communities in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province. “Any escalation might empower radical groups, embolden opposition movements throughout the region, and exacerbate sectarian polarization,” added Dr Bitar. [11] Such turmoil also raises the specter of separatist movements in Iran’s peripheral areas that are home to the country’s minority ethnic groups with their own histories of secessionist drives, such as ethnic Arabs, Kurds, or Baluch people. Such developments would pose acute security risks for countries like Pakistan and Turkey. From this perspective, the danger lies not only in Iran’s internal fragmentation but in the wider regional contagion that would follow. In turn, the Gulf states have a vested interest in maintaining stability in the region even though authoritarian structures continue. Woertz, director of the German Institute of International and Security Affairs, argues that “the leaders of the Gulf states apparently prefer to rely on the familiar old regime rather than getting involved with a new, potentially unknown faction,” although they still have strong reservations about the Iranian regime. [12] In simple words, most regional actors approach the prospect of escalation through a lens of risk aversion rather than ideological alignment. The prevailing judgment among leaders in most regional countries is that escalation is strategically irrational, while maintaining the status quo remains the least dangerous option. In recent years, the Gulf states have taken significant actions to improve relations with Iran as part of a policy of détente, which, in their view, has proven effective. “They don’t want to jeopardize that.” Woertz notes. From their perspective, “the devil they know” is preferable to the instability that could spill over into the Gulf, generate waves of refugees, and disrupt trade. The Arab Spring may also serve as a reference point, demonstrating that regime collapse does not necessarily bring clarity and stability but rather prolonged instability. [13] Iran is a known actor; its red lines, internal constraints, and regional patterns of behavior are familiar. By contrast, a post-Islamic Republic Iran-especially one emerging from a protest movement that is not monolithic-could be much less predictable. Moreover, the monarchies in the Gulf states fear a “contagion effect,” namely the possibility that the collapse of the Iranian regime and the emergence of a democratic-liberal political system in its place would inspire waves of protest in the region (as could have happened following the 2009 protests in Iran and the subsequent development of the Arab Spring). Finally, the collapse of the Iranian regime could also lead to a dramatic shift in the regional balance of power and a significant strengthening of Israel. Iranian hostility toward Israel, even at the rhetorical level, helps preserve a familiar equilibrium in the region.

3. The third reason why Sunni countries oppose US military strikes on Iran is that they worry about expanding Israeli influence: If Iran collapses or weakens, US-backed Israel’s influence in the Middle East could rapidly increase, posing a threat to Arab countries in the region.Arab governments that once tolerated the idea of US-led regime change in Iran now urge restraint, recognizing that Israeli expansionism has become the region’s main threat. Only a few years ago, many Arab countries, particularly in the Gulf, may have viewed a US attack on Iran for regime change favorably. For decades, they regarded Iran with deep suspicion, often treating it as the region’s main threat. But now, as US President Donald Trump reportedly mulls exactly such an attack, Arab leaders, including Gulf rulers long at odds with Iran, are lobbying the US administration not to carry out military strikes on Iran. Even Gulf governments that have engaged in indirect conflict with Iran — such as Iran’s regional rival, Saudi Arabia — do not support US military action there, according to analysts who study the region. That is partly because the monarchies of the Gulf worry that the ripple effects of escalating US-Iran tensions, or possible state failure in Iran, would harm their own security, undermining their reputation as regional safe havens for business and tourism. But it is also because some Gulf governments have come to see Israel, Iran’s archenemy, as a belligerent state seeking to dominate the Middle East. They believe that Israel could pose a greater threat to regional stability than an already weakened Iran does. In the wake of 7 October 2023 when the Hamas attacked Israel, Arab states have increasingly regarded Israel, not Iran, as the foremost threat to regional stability. “Ever since the US essentially lifted all restraints on Israel during the Biden administration, regional players have started to see Israel’s aggressive foreign policy as a direct and unmanageable threat. Israel has bombed seven countries in the region since 7 October 2023,” Dr Trita Parsi, Executive Vice President of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, told TNA. “Bombing Iran goes against the calculus and interests of the Arab Gulf States,” said Bader al-Saif, a history professor at Kuwait University. “Neutralizing the current regime, whether through regime change or internal leadership reconfiguration, can potentially translate into the unparalleled hegemony of Israel, which won’t serve the Gulf States.” Yasmine Farouk, the Gulf and Arabian Peninsula project director at the International Crisis Group, argues that Gulf countries are worried about “the chaos that a regime change in Iran would cause in the region” and how Israel might use “that vacuum.” For 27 months since 7 October 2023, Arab leaders have watched Israel’s rampage throughout the region, in pursuit of its “Greater Israel” project, an expansionist biblical vision for territory spanning from the Euphrates River in Iraq to the Nile River in Egypt. To this end, Israel has significantly expanded its illegal occupation of Arab lands. Not only has Israel carried out genocide in Gaza and indicated its plans to take the territory over, but it has also deepened its hold in the West Bank, Syria and Lebanon. Perhaps most alarming for Arab leaders, after months of Netanyahu openly declaring his expansionist ambitions, was Israel’s unprecedented assault on Qatar, a US ally, in September 2025. That escalation had been preceded only a few months earlier, in June 2025, by Israel convincing the US to bomb Iran in an assault aimed at destroying Iran’s nuclear facilities and ensuring Israel remains the region’s sole nuclear power. The Israeli strike rattled Gulf governments not only because many have been courted by Israel as potential allies (signing the Abraham Accords) in recent years, but also because they, like Israel, had long regarded the US as their main security guarantor. “If the alliance with the US does not protect you from what these countries see as Israel’s designs for regional hegemony, then you will need a new coalition to balance against Israel,” Yasmine Farouk added. “Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Pakistan have moved in this direction. Soon after the Israeli attack on Qatar, Saudi Arabia’s de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, signed a security pact with nuclear-armed Pakistan. Though Iran is not officially part of this coalition, it does serve as a buffer against Israel. Chaos in Iran - or a pro-Israeli puppet being installed in Iran - is seen as a very dangerous blow to the effort to balance against Israel’s increasingly aggressive regional posture.” In short, Israel’s aim of absolute regional hegemony has never been clearer, and a US strike on Iran would represent both an extension of Israeli aggression and an expansion of its regional power. This is the structural shift at the heart of Arab opposition to a potential US attack on Iran. Moreover, it is also worth noting that Arab countries have themselves moved diplomatically closer to Iran in recent years, in part because of Israeli aggression and expansionism. The Saudi Arabia and Iran restored diplomatic relations in 2023 and moved closer after Israel’s attack on Qatar in September 2025. Iran’s relationship with Egypt has also improved. Recent events, and in particular Israel’s unchecked aggression and territorial expansion, have forced a structural shift in how Arab states assess regional threats. Gone, at least for now, are the days when Saudi Arabia viewed Iran as its foremost enemy, when Qatar saw Saudi Arabia as its principal threat, or when Egypt treated Qatar as the chief source of regional instability. Increasingly, Arab regimes, with perhaps the exception of the UAE, now view Israel as the region’s most destabilizing force. Israeli expansionism, its willingness to strike across borders without regard for accepted international norms, and its open pursuit of regional hegemony have fundamentally changed how Arab leaders assess risk.

In early 2026, the strategic landscape of the Middle East is shaped by a striking convergence: while many regional governments deeply distrust Iran’s intentions and regional behaviors, there is a near-universal assessment that a US military intervention would be profoundly destabilizing. Across the Gulf, the Levant, and Turkey, leaders increasingly see war with Iran not as a solution to regional insecurity, but as a catalyst for economic shock, domestic unrest, and long-term strategic degradation. [14] The specific reason why a specific country opposes US military attacks on Iran is as follows. 1. Saudi Arabia Saudi Arabia’s position reflects a decisive shift from confrontation toward risk management. Saudi Arabia has signaled a refusal to facilitate US strikes, including denying the use of its airspace, driven primarily by vulnerability rather than sympathy for Iran. Iran maintains the capability to disrupt shipping through the Strait of Hormuz, and to target Saudi Arabia’s energy infrastructure — most notably Abqaiq, Khurais, and Ras Tanura — with missiles and drones, as demonstrated in 2019. Even limited retaliation would disrupt global energy markets and severely undermine ‘Vision 2030’, which depends on foreign investment, tourism, and the perception of internal stability. Saudi leadership also assesses that a regional war would divert financial and political capital from other priorities, including regional diplomacy and post-Gaza reconstruction efforts that Saudi Arabia increasingly frames as part of its leadership role rather than a purely humanitarian endeavor. 2. Qatar For Qatar, the risks are existential. Qatar shares the world’s largest natural gas field with Iran, making sustained stability in the Gulf essential to its economic model. Any conflict that disrupts production, shipping, or joint field management would directly threaten state revenues. Compounding this exposure is Qatar’s hosting of Al Udeid Air Base, which would almost certainly be viewed by Iran as a legitimate retaliation target. Qatari strategy has long relied on diplomatic mediation as a form of deterrence; a US intervention would collapse this posture and force Doha into a conflict it has consistently sought to avoid. 3. United Arab Emirates (UAE) The UAE maintains a public stance of strategic neutrality, but this reflects calculated self-interest rather than ambiguity. Abu Dhabi’s leadership is acutely aware that its global financial hub status, logistics networks, and tourism economy are predicated on regional calm. A conflict with Iran would endanger shipping through the Strait of Hormuz, threaten port infrastructure, and likely trigger capital flight from Dubai. Despite ongoing tensions with Iran and security coordination with Israel, Emirati planners judge that the economic costs of war would far exceed any prospective strategic benefit from weakening Iran. 4. Kuwait, Bahrain, and Oman The smaller Gulf states such as Kuwait, Bahrain, and Oman view US intervention in Iran primarily through the lens of exposure. Kuwait faces strong parliamentary and public resistance to involvement in another regional conflict. Bahrain, home to the US Fifth Fleet, recognizes that its territory would be among the first targets in any Iranian retaliation. Oman, which has long positioned itself as a neutral intermediary, sees military escalation as incompatible with its foreign policy identity and economic resilience. All three countries fear that war would inflame sectarian tensions, disrupt trade, and undermine already fragile domestic social contracts. 5. Egypt Egypt’s opposition is rooted in regime insecurity and economic fragility. The Suez Canal remains Egypt’s most critical source of foreign currency, and any regional conflict that disrupts Red Sea or Gulf shipping would have immediate fiscal consequences. Egyptian leaders also fear that war with Iran would energize domestic protest movements and Islamist networks, exploiting anti-US sentiment amid existing economic hardship. For Egypt, a US–Iran conflict represents a high-impact destabilizing event rather than a distant strategic concern. 6. Jordan Jordan’s position reflects chronic vulnerability. Jordan is already under severe economic strain and hosts a large refugee population relative to its size. Regional war could disrupt trade routes, risk spillover violence, and inflame public opposition to both Israel and the US. Jordanian authorities assess that even limited escalation could translate into disproportionate domestic instability, undermining the monarchy’s balancing act between internal legitimacy and external alignment. 7. Turkey Turkey’s concerns center on displacement and strategic autonomy. Turkey fears that conflict in Iran could generate large-scale refugee flows toward its eastern border, exacerbating domestic backlash against existing refugee populations. Turkey also relies on Iranian energy imports and has invested heavily in maintaining a flexible posture between Iran, NATO, and Russia. A US intervention would collapse this balancing strategy, impose economic costs, and complicate Ankara’s efforts to position itself as a regional diplomatic actor, including in post-Gaza reconstruction initiatives. 8. Israel Israel remains the sole regional actor publicly supportive of weakening or dismantling the Iranian regime. Privately, however, Israeli security assessments are more cautious. After prolonged military operations across multiple fronts, the Israeli Defense Force faces resource constraints, personnel fatigue, and growing concerns about air defense sustainability. Israeli planners increasingly judge that a US intervention would not be likely to produce rapid Iranian regime collapse and more likely to trigger a prolonged multi-front conflict involving Hezbollah, Iraqi militias, and other Iranian-aligned actors. There is also recognition that external attack could consolidate Iranian domestic support for the regime rather than fracture it.

This paper explained the relationships between Shiite Iran and Suni Arab countries and why those Sunni Muslim nations, which do not feel favorable toward Iran, oppose US military strikes against Iran. This paper explained that Sunni Muslim nations oppose US military strikes against Iran for three reasons: The first reason why Sunni Arab countries oppose US military strikes on Iran is that they worry about potential retaliatory attacks on their own soil by Iran and economic fallout and disruption. The second reason why Sunni countries oppose US military strikes on Iran is that they worry about regional instability and insecurity caused by US military strikes. The third reason why Sunni countries oppose US military strikes on Iran is that they worry about the Israeli influence expansion.

[1] Barin, Mohsen (31 December 2025). "Iran's economic crisis, political discontent threaten regime". DW News. [2] https://www.timesofisrael.com/irans-president-warns-us-attack-on-supreme-leader-would-mean-full-scale-war/ [3] https://www.politico.com/news/2026/01/17/trump-to-politico-its-time-to-look-for-new-leadership-in-iran-00735528?_kx=LSFywwe4GSg_lcFWo5DyId8VKdphy2F0zhlZVneJnA97jKgVYFyty4cB80GJkTHR.U5D8ER&utm_id=01KF7GKF35MAAW8BRA143VFM9M&utm_medium=campaign&utm_source=Klaviyo [4] https://www.cfr.org/photo-essay/sunni-shia-divide#:~:text=Saudi%20Arabia%20has%20a%20sizable,to%20Saudi%20and%20Iranian%20sources. [5] https://www.cfr.org/photo-essay/sunni-shia-divide#:~:text=Saudi%20Arabia%20has%20a%20sizable,to%20Saudi%20and%20Iranian%20sources [6] https://www.inss.org.il/publication/gulf-iran-usa/ [7] https://www.inss.org.il/publication/gulf-iran-usa/ [8] https://www.inss.org.il/publication/gulf-iran-usa/ [9] https://www.dw.com/en/why-the-gulf-states-are-wary-of-a-strike-on-iran/a-75593784 [10] https://www.dw.com/en/why-the-gulf-states-are-wary-of-a-strike-on-iran/a-75593784 [11] https://www.newarab.com/analysis/why-middle-east-fears-us-israel-attack-iran [12] https://www.newarab.com/analysis/why-middle-east-fears-us-israel-attack-iran [13] https://www.inss.org.il/publication/gulf-iran-usa/ [14] https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/why-middle-eastern-states-oppose-us-military-inter vention-in-iran/

First published in :

World & New World Journal

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!