From Promised Land to Forced Exodus: Faces of Deportation in Latin America and the Caribbean

by Rocío de los Reyes Ramírez

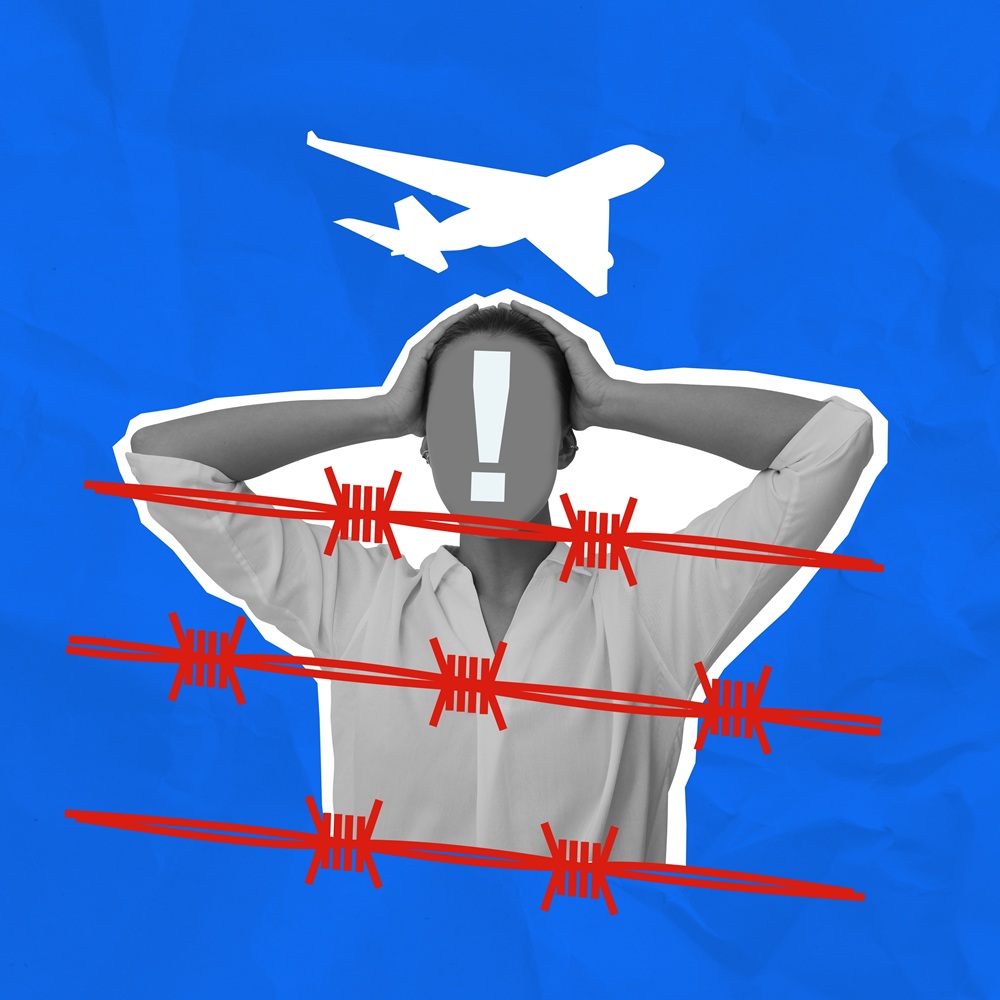

한국어로 읽기 Leer en español In Deutsch lesen Gap اقرأ بالعربية Lire en français Читать на русском Abstract: Migration policies in Latin America and the Caribbean have adopted a more restrictive and punitive approach, influenced by external pressures, especially from the United States. Deportations, detentions and dissuasive measures have intensified, in a context of increasing criminalisation of migrants. Cases such as El Salvador and the Dominican Republic reflect the use of severe control strategies, which have been criticised for possible human rights violations. These practices, although justified on security grounds, generate regional tensions and deepen the vulnerability of displaced populations. Keywords:Latin America, migration, Donald Trump, Ibero-America, deportations, forced returns. Introduction Deportations in Latin America and the Caribbean have undergone significant changes in recent years, reflecting both migration dynamics and international policies. The region has witnessed an increase in migratory movements, driven by economic crises, political conflicts and natural disasters. Latin American population movement configurations have been immersed in a dynamic whose magnitude and urgency have intensified since the beginning of 2025: that of forced returns and mass deportations, driven by changes in the migration policies of receiving countries such as the United States and Mexico. The re-election of Donald Trump has marked a tightening of immigration control measures, with an increase in raids and expulsions of undocumented migrants. But this is not a new phenomenon: mass deportations and forced returns in Latin America have deep roots in the region's history, with moments of particular intensity in different periods. It is not a recent phenomenon, nor is it exclusive to contemporary dynamics. Throughout its history, the region has been the scene of multiple processes of expulsion, forced return and internal displacement, intimately linked to contexts of political violence, economic change, structural racism and state strategies of population control. Already during the 19th century, the consolidation of nation states brought with it policies of exclusion that sought to shape national identity to the detriment of certain groups. In Mexico, after the 1910 Revolution, the Chinese community was persecuted and expelled in an episode that combined racism, economic crisis and exacerbated nationalism.1 In Argentina, during the 1880s, the military campaigns known as the "Conquest of the Desert" provoked massive forced displacements of indigenous peoples to marginal areas, marking a pattern of invisibilisation and internal expulsion.2 In the Caribbean, the dynamics of deportation were also marked by racial and economic conflicts. The Dominican Republic, under the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo in the 1930s, carried out the so-called “Parsley Massacre” (1937), where thousands of Haitians were killed or forcibly expelled in order to 'whiten' the border and reaffirm Dominican national identity³. And in Cuba, after the triumph of the 1959 Revolution, the flow of political exiles to the United States intensified, generating waves of departures that, in some cases, were accompanied by pressure and coercion from the Castro regime. Central America in the second half of the 20th century was marked by civil wars and authoritarian regimes. El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua experienced profound humanitarian crises that provoked a massive flight of their citizens. Many of these refugees were received in Mexico, Costa Rica or the United States, but after the Peace Accords of the 1990s, forced return policies emerged that did not always provide adequate conditions for reintegration. The case of Guatemala is emblematic: the return of refugees from Mexico, coordinated in part by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), was fraught with difficulties, as many of the returnees were returning to territories still without security guarantees.3 The United States played a key role in contemporary deportation processes. The passage of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) in 1996 was a paradigm shift, facilitating the deportation of immigrants convicted of minor crimes, which particularly affected Latin American communities.4 Honduras and El Salvador were particularly hard hit by these policies. Many of the young deportees had lived most of their lives on US soil and, upon their return to contexts of poverty and violence, found in gangs, such as MS-13 and Barrio 18, a means of survival and even a sense of belonging.5 Similarly, in South America, the military dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s also resorted to exile and deportation as mechanisms of political control. In Chile, following the 1973 coup d'état, tens of thousands of people were forced into exile, and opponents captured abroad were often smuggled into the country under the coordination of Operation Condor. Argentina replicated these patterns, using illegal deportations and forced disappearances as systematic tools of political repression. More recently, in the insular Caribbean, contemporary dynamics also reveal patterns of selective deportation. In the Bahamas and Trinidad and Tobago, deportations of Haitian and Venezuelan migrants in an irregular situation have intensified in recent years, often in conditions of human rights violations, reproducing old logics of racial and socio-economic exclusion. These examples show that deportations in Latin America and the Caribbean are not isolated or temporary events: they are part of structural patterns that have accompanied state-building processes, the dynamics of internal violence and international population control strategies. Today, in a scenario of growing migratory pressure and increasingly restrictive policies in the main receiving countries, the region is once again facing old challenges in new forms. The echoes of history resound in the new faces of forced exodus, marking a present in which mass expulsions once again occupy a central place on the regional agenda. The United States and the tightening of immigration policy The arrival of Donald Trump for a second presidential term in January 2025 marked an even more severe shift in US immigration policy. While his first administration (2017-2021) had already been marked by restrictive measures, his return to power brought with it not only the restoration of old border control programmes, but also their radicalisation, in a context of growing domestic pressure and political polarisation. Trump has not only taken up policies such as the "Remain in Mexico" policy or the limitation of access to asylum: he has also expanded the margins of action of immigration agencies, hardening the official rhetoric against migrants -especially Latin Americans- and rescuing old legal instruments to justify new practices of accelerated deportation. This new phase is characterised by a combination of administrative, legal and operational measures that seek to deter irregular migration through the restriction of rights, the intensive use of detention and deportation, and the strengthening of pressure mechanisms on countries of origin and transit. One of the first symbolic and practical steps of this new policy was the reinstatement of the programme officially known as the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), more popularly known as “Remain in Mexico”. It had originally been implemented in 2019, during his first term, and partially suspended during Joe Biden's administration from 20216. However, after his re-election, Trump not only reactivated it, but also tightened it, broadening its scope and further reducing the possibilities for asylum seekers to await processing on US soil. On 20 January 2025, the US president signed the executive order to reinstate this programme, which obliges asylum seekers to wait in Mexican territory while their cases are resolved in US courts.7 This has led to diplomatic tensions between the two countries. The president of Mexico, Claudia Sheinbaum, has expressed her rejection of this policy, describing it as a unilateral decision that affects national sovereignty and the human rights of migrants. The Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Juan Ramón de la Fuente, reiterated that Mexico is not obliged to accept this measure and that mechanisms will be sought to protect the migrants affected.8 While in its initial version the programme had already forced tens of thousands of asylum seekers to stay in Mexican border cities - leading to the formation of makeshift camps in places such as Matamoros and Tijuana - the reinstatement in 2025 accentuated this phenomenon. More categories of applicants, including minors and persons in vulnerable situations, are now susceptible to refoulement, increasing the pressure on border areas characterised by insecurity, poverty and criminal violence.9 Thus, the camps, which already existed precariously since the first implementation of the programme, have expanded and degraded throughout 2025, creating even more severe humanitarian emergencies. International organisations and human rights organisations have warned that the reactivation and tightening of the MPP violates essential principles of international law, such as non-refoulement, and exposes applicants to serious risks of violence, kidnapping and human trafficking.10 The Mexican government, for its part, has implemented some measures to support migrants, such as the "ConsulApp" application and the "Mexico te abraza" plan (Mexico hugs you), but challenges remain in ensuring their safety and well-being.11 Ultimately, this would tie in with the implementation of 'safe third country' agreements, as some analysts have interpreted it. And although Mexico has not signed any protocols, in practice, these current policies de facto position it in this role. This is because during Donald Trump's first term in office, the US signed agreements with several Central American countries to designate them as “safe third countries”.12 These include Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. These agreements required asylum seekers passing through these countries to seek protection there before arriving in the US. It was a controversial move that generated criticism of conditions in these countries and their capacity to handle the flow of migrants. Although formally presented as instruments to share the burden of international protection, in practice these protocols served to divert and contain asylum seekers in nations that did not have the material and legal conditions to guarantee their safety and basic rights. Particularly in the case of Guatemala, which was the only one to actually implement them in 2019, reports documented how migrants transferred from the US faced a total absence of effective asylum procedures, lack of humanitarian protection, and direct exposure to extreme violence and poverty.13 During the Biden administration (2021-2024), these agreements were formally suspended, however, it appears that the door is now being reopened. The new administration has signalled its intention to renegotiate and expand these instruments. In this way, they are once again at the centre of a more aggressive migration containment strategy, de facto limiting access to asylum in the US and increasing the vulnerability of thousands of migrants expelled to unsafe territories. El Salvador, for its part, has emerged in 2025 as the first Latin American country to formalise an agreement that, without officially naming itself as a "safe third country", operates de facto as such. The agreement, announced by President Nayib Bukele himself as "unprecedented", establishes that El Salvador will accept migrants deported from the United States - including those considered highly dangerous - coming not only from the Central American Northern Triangle, but also from other regions of the continent and the Caribbean.14 Unlike the Asylum Cooperation Agreements (ACAs) signed in 2019 and suspended in 2021, this new pact is not limited to the processing of asylum applications but directly assumes the reception and custody of deported persons, with no guarantee that they will be able to restart a regular migration process. Various sources agree that this is an advanced form of border externalisation: the northern giant transfers not only the management of flows, but also the custody of people considered undesirable or dangerous.15 Although the agreement has not been accompanied by specific legal reforms in the US, it has been consolidated through bilateral negotiations that contemplate financial compensation for El Salvador. Human rights organisations have warned that this strategy could be replicated with other governments receptive to these cooperation formulas in exchange for financial incentives. In this context, negotiation attempts have already begun with Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Colombia,16 countries that are being considered to host regional asylum processing centres. Although these mechanisms have not been formalised as "safe third country agreements" in the strict sense, several organisations have warned that they operate under a similar logic: the transfer of migratory responsibilities to nations with limited institutional capacity and contexts of violence or political crisis.17 The "pact" with El Salvador also contemplates the use of national penitentiary centres to detain a large part of these deportees, without a detailed analysis of their legal situation. Although mention has been made of the sending of some profiles considered to be at risk to the Terrorism Confinement Centre (Spanish: Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo, abbreviated CECOT), the implications of this prison model deserve specific treatment, which will be addressed in the following section. Along with the reinstatement of this programme, the new US administration has pushed through a series of measures that further restrict access to the right to asylum for those seeking to enter the US from Latin America and the Caribbean. One of the main changes has been the reintroduction of stricter standards for the initial submission of asylum applications. Migrants must now demonstrate from the outset a "credible fear" of persecution with strong documentary evidence,18 a much higher standard of proof than in previous years. This policy has drastically reduced the percentage of applicants who make it through the first asylum interview. Similarly, as part of the tightening of these immigration policies, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has experienced a significant expansion of its powers. This expansion has translated into both an increase in its budget and greater operational discretion to carry out detentions and deportations. During 2025, the budget allocated to ICE increased by 15% over the previous year, reaching record amounts to fund detention centres, internal patrol operations and tracking technology for undocumented immigrants.19 This budget boost has allowed for increased detention operations in places considered "sensitive", such as hospitals, schools and churches, which were previously relatively protected under more restrictive guidelines. But ICE's expansion has not been limited to issues of operational volume, but also of legal scope. The use of internal administrative warrants (without judicial intervention) for the detention of immigrants suspected of minor immigration infractions has been reactivated.20 This measure has been widely criticised by human rights organisations, which point to the weakening of procedural safeguards for detainees and the risk of arbitrary detention. ICE has also strengthened its cooperation with state and local police forces through programmes such as 287(g), which allow police officers to act as immigration agents.21 This collaboration has been particularly controversial in states such as Texas and Florida, where racial profiling and civil rights violations have been reported. The tightening of detention practices has had a direct impact on Latin America and the Caribbean, with a significant proportion of those deported in 2025 coming from countries such as Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and, to an increasing extent, Venezuela and Haiti. Thus, the expansion of ICE's power has not only transformed the internal migration landscape in the US but has also intensified the dynamics of forced return throughout the region. However, the shift towards a more punitive approach is not limited to contemporary operational frameworks: the current government has also begun to recover legal tools from the past, such as the Alien Enemies Act, to legitimise new forms of exclusion, detention and deportation. This is a 1798 law that allows the executive to detain and deport citizens of countries considered enemies in times of war. Although historically this law has been applied in wartime contexts, such as during the Second World War, its invocation in a period of peace has generated intense legal and political controversy.22 On 14 March 2025, Trump signed a presidential proclamation designating the Venezuelan Tren de Aragua gang as a national security threat, calling their presence in the US an "irregular invasion". Under this justification, it authorised the immediate detention and deportation of Venezuelan citizens suspected of links to the organisation, without the need for warrants or conventional legal processes. The president later denied having signed it, attributing the responsibility to his Secretary of State, Marco Rubio.23 The implementation of this measure resulted in the accelerated deportation of hundreds of Venezuelans to El Salvador, many of whom had no criminal record and some of whom had legal immigration status in the US, including Temporary Protected Status (TPS).24 Civil rights organisations, such as the ACLU, filed lawsuits alleging that the application of the law violated due process and constitutional protections. 25In response, several federal judges issued orders temporarily halting deportations and requiring judicial hearings before any deportations. But despite the judicial restrictions, the administration continued with the deportations, arguing that the orders did not apply to flights already underway or over international waters. This stance was criticised for defying judicial authority and for using a wartime law for contemporary immigration policy purposes.26 The reactivation of the Alien Enemies Act in 2025 has sparked a national debate on the limits of executive power and the protection of immigrant rights, highlighting the tension between national security and civil liberties in US immigration policy. Not only that: all these measures have generated a wave of mass deportations that have not only overwhelmed the capacity of reception systems in Latin American countries, but have also had a direct impact on the structure of separated families and local communities, often lacking the resources to provide adequate reintegration processes. In Mexican border cities such as Ciudad Juárez, Matamoros and Tijuana, makeshift camps have multiplied, where thousands of people who have been deported or are awaiting a migration resolution live in extremely precarious conditions, as mentioned above. In Central America and the Caribbean, the forced return of migrants - some of them with weak links to their countries of origin or with criminal records - has reactivated dynamics of exclusion, stigmatisation and, in some cases, violence. Taken together, these actions reflect a regional trend towards the externalisation and criminalisation of migration, where migration responsibilities are shifted to countries in the global south and managed through punitive rather than humanitarian strategies. The consequences of these measures are not only individual but also reshape the social and political fabric of the entire region. Detention centres and new deportation dynamics Recent transformations in US immigration policy have not only translated into regulatory and diplomatic tightening: they have also reconfigured places of confinement and removal processes. Mass deportationsalready being pushed since 202327 , have now coincided with a renewed detention architecture, in which confinement and surveillance are not limited to US territory but projected beyond its borders. This phenomenon has given rise to new dynamics of migration management, in which detention centres play a central role. In addition to ICE detention centres on US soil, there is now a network of prison and surveillance facilities located in countries receiving deportees, frequently promoted or supported by Washington under the bilateral security cooperation agreements we have been discussing. The most visible case is that of the CECOT (Terrorism Confinement Center) in El Salvador which, although initially conceived as a tool against local gangs, has begun to receive Salvadoran citizens deported from the US with criminal records.28 The use of this type of facility marks a worrying twist: the systematic criminalisation of deportees and their immediate insertion into highly restrictive prison circuits. The policy of automatic association between migration and criminality has led many deportees to be considered not as citizens to be reintegrated, but as threats to be neutralised. This logic is reinforced by the Salvadoran government's narrative, which has actively promoted CECOT's image of success before the international community, using figures on homicide reduction and territorial control as arguments of legitimacy, albeit with a strong questioning of judicial opacity and arbitrary detentions.29 This transnational prison model has profound human rights, social reintegration and regional security implications. Far from offering sustainable solutions, it reinforces the stigmatisation of returned migrants and multiplies barriers to their inclusion in communities of origin. In turn, it turns countries such as El Salvador into functional extensions of the US immigration and penal system, fuelling political and social tensions.30 When in March 2025, the US deported 238 Venezuelan nationals to CECOT on charges of belonging to the Tren de Aragua criminal group, the move was widely criticised by human rights organisations and international governments as a violation of due process and the fundamental rights of migrants. The Salvadoran government, for its part, defended the action, claiming that the deportees were "proven criminals" and that their incarceration in this centre was part of a strategy to combat transnational organised crime.31 However, relatives of the detainees and humanitarian organisations have denounced that many were identified as members of the Tren de Aragua based solely on tattoos or physical characteristics, without concrete evidence. The situation has generated diplomatic tensions, especially with Venezuela, whose government has requested the intervention of international bodies to protect its citizens and has described the deportations as a "crime against humanity".32 To date, there is no record of similar agreements between the US and other Latin American countries, such as Guatemala or Honduras, to receive deported migrants in high-security prisons. Although these countries have announced plans to build mega-prisons, there is no public evidence that they are being used to house deportees from the US. In parallel, the so-called policy of self-deportation has gained momentum: an increasingly documented phenomenon in which thousands of migrants voluntarily choose to return to their countries of origin in fear of being arrested, separated from their families or detained in inhumane conditions. This practice, indirectly promoted by the tightening of the legal and police environment, represents a form of covert expulsion, in which the state does not need to apply force: it is enough to install fear. 33 The Trump administration has intensified this strategy through various measures. These include the implementation of the CBP Home app, which allows undocumented immigrants to manage their voluntary departure from the country. In addition, "incentivised self-deportation" programmes have been announced, offering financial assistance and coverage of transportation costs to those who decide to return to their countries of origin. These initiatives have been presented as humanitarian solutions, although they have been criticised by human rights organisations as coercive and discriminatory. The government has also imposed economic sanctions on immigrants with active deportation orders, such as daily fines of up to a thousand dollars, with the aim of pressuring them to leave the country voluntarily. These policies have been accompanied by media campaigns displaying images of immigrants arrested and charged with serious crimes, seeking to reinforce the perception of threat and justify the measures adopted. These actions have generated a climate of fear and uncertainty among migrant communities, leading many to opt for self-deportation as the only alternative to avoid detention and family separation. However, experts warn that this decision may have long-term legal consequences, such as the impossibility of applying for visas or re-entering the country for several years.34 It has come to the point, last week, of arresting Hannah Dugan, a Miilwaukee County judge by the FBI, allegedly accused of assisting a documented immigrant who was to be detained.35 In this context, the self-deportation policy is yet another tool in the Trump administration's restrictive and punitive approach to migration, prioritising deterrence and control over the protection of human rights and the search for comprehensive solutions to the migration phenomenon. The proliferation of self-deportations and increasing allegations of human rights violations soon escalated into the judicial arena. As claims of arbitrary detention, inhumane conditions of confinement and family separation increased, various courts began to examine the legal limits of these policies. The climax came in April 2025 with the Supreme Court's decision in Trump v. J. G. G. G.36 , which assessed the constitutionality of certain expedited deportation practices applied to Venezuelan and Central American asylum seekers. Although the Court did not completely invalidate the executive measures, it did set important limits: it recognised the right to a pre-removal hearing in cases where there is a credible risk of persecution and called on Congress to urgently review the immigration legal framework.37 In addition, the court ruled that legal challenges must be brought in the district where the detainees are located, in this case, Texas, and not in Washington D.C. This Supreme Court ruling marks a turning point. While it does not dismantle the mass deportation apparatus, it introduces legal brakes that could slow down or modulate its application. Congress, under pressure from the ruling, now faces the challenge of reforming a dysfunctional, polarised and increasingly judicialised immigration system. In the short term, federal agencies such as ICE and CBP will have to adjust their operational protocols to avoid litigation, which could generate internal tensions and new immigration outsourcing strategies. Ultimately, this decision opens a new scenario in which immigration policies will have to face not only social and international scrutiny, but also the limits imposed by constitutional law and the US judicial system. Expulsions in the Caribbean: the case of the Dominican Republic In the context of a regional tightening of migration policies, the Dominican Republic has significantly intensified its efforts to control irregular immigration, especially from Haiti. Under the administration of President Luis Abinader, a policy of mass deportations has been implemented, which has raised concerns both domestically and internationally. The deportations have taken place against a backdrop of growing social fear of cross-border crime and the infiltration of armed actors from the neighbouring country. In this context, the government has reinforced border control with a combination of military presence, surveillance technology and migration deterrence measures. Between January and December 2024, the Dominican authorities deported more than 276,000 foreigners in an irregular migratory situation, the majority of whom were Haitian nationals38 . This figure represents a significant increase compared to previous years and reflects a systematic and sustained deportation policy.39 Precisely in October 2024, the government announced a plan to deport up to 10,000 Haitians per week, which intensified operations across the country. These operations include raids in neighbourhoods, arrests in hospitals and the demolition of informal settlements inhabited by Haitians. One of the most controversial practices has been the deportation of pregnant and lactating Haitian women directly from public hospitals. Human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and UN experts have condemned these actions as inhumane and discriminatory. Cases have been documented of women being deported while in labour , putting their health and that of their children at risk.40 The Dominican government defends these policies as necessary to maintain order and national security, arguing that they are carried out in accordance with the law. However, international criticism has mounted, with allegations that these mass deportations violate fundamental human rights and aggravate the humanitarian crisis in Haiti. The situation has generated diplomatic tensions between the two countries and has been the subject of concern from the international community, which is urging the Dominican Republic to review its migration policies and ensure respect migrants' rights. This case exemplifies the challenges faced by Latin American and Caribbean countries in managing migration flows, especially when humanitarian crises, security policies and bilateral tensions are combined. Ultimately, the Dominican response - although framed by legitimate sovereignty concerns - also raises profound questions about the proportionality of measures, respect for due process and regional co-responsibility in the face of the Haitian collapse. Conclusion The Latin American and Caribbean region is going through a critical moment in terms of migration. Recent waves of mass deportations, forced returns - direct or induced - and new border control strategies have deepened a regional crisis that has been brewing for years. These dynamics, far from being isolated phenomena, are part of a systematic strategy of migration containment promoted by the US, where political discourse and practice have turned migrants into scapegoats for all national ills. Donald Trump has been the most visible - and aggressive - face of this policy. His obsession with migrants, especially those from Latin America and the Caribbean, has resulted in an institutional architecture designed to curb mobility at any cost. Under his leadership, not only have physical and legal walls on the southern border been reinforced, but programmes such as "Remain in Mexico", safe third country agreements and, more recently, the controversial use of regulations such as the Alien Enemies Act have been promoted. At the core of this strategy is a profoundly punitive vision that identifies the migrant as a threat, a potential enemy or an invader, thus legitimising policies of mass exclusion and systematic expulsion. The impact of these policies in Latin America and the Caribbean is profound. Beyond the numbers, what is at stake is the stability of societies already marked by inequality, violence and institutional fragility. Mass deportations - affecting not only border crossers but also those who had already put down roots in the US - are overwhelming the capacities of receiving states. Every week, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Haiti, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic receive contingents of returnees who must be reintegrated in contexts of structural precariousness. In this context, the arrival of thousands of deported or self-deported Venezuelans in places such as CECOT in El Salvador illustrates a new phase: the direct criminalisation of migrants. The use of mega-prisons as a migration management tool represents a worrying drift, where security replaces integration and fear replaces law. Alongside this, the policy of self-deportations has gained strength, a form of covert expulsion in which the state does not need to apply force: it is enough to install fear. Families choose to return voluntarily for fear of being detained, separated or held in inhumane conditions. In recent months, this practice has even been economically incentivised, with programmes promoted by the Trump Administration offering to pay for the return ticket, as if it were a favour, when in reality it is a forced flight disguised as a personal choice. This has generated a far-reaching reconfiguration of migration. The fracturing of family networks, the interruption of the flow of remittances and the uncertainty over the legal status of millions of people have altered not only regional mobility, but also the economic models that depend on exile as a source of income. Remittances, which represent a significant percentage of GDP in countries such as Honduras and El Salvador, are threatened by these return policies, directly affecting consumption, community investment and the ability to sustain millions of households. Moreover, the legal and judicial system now faces its own limits. The intervention of the US Supreme Court has highlighted the constitutional challenges to these measures, opening a space for legal dispute over how far the executive can go in its crusade against migration. However, the effects are already underway. The reality is that many Latin American and Caribbean countries are assuming, voluntarily or forcibly, the role of advanced border of the global North. The overall balance is bleak: a utilitarian vision of human mobility is imposed, whose fate depends more on electoral cycles in the north than on their fundamental rights. However, resistance is also emerging: from the courts to the streets, through grassroots organisations, solidarity networks and proposals for fairer regional policies. The future of mass deportations is not set in stone. It will be decided in multiple scenarios: in presidential speeches in Washington, but also in the legal decisions of the courts; in public policies in Bogotá, San Salvador or Santo Domingo, but also in the mobilisation capacity of the societies affected. Latin America and the Caribbean have an opportunity and a responsibility: not to resign themselves to the role of passive recipients of an imposed policy, but to build a regional strategy for mobility, rights and dignity. References 1 CHAO ROMERO, Robert. The Chinese in Mexico, 1882-1940. University of Arizona Press, 2010.2 VIÑAS, David. Indians, army and frontier. Siglo XXI Editores, 1982.3 FERRER ,Ada. Cuba: An American History. Scribner, 2021.4 AMERICAS ALLIANCE. 28 years of IIRIRA: a horrible legacy of a white supremacist and deeply xenophobic immigration law. 30/9/24. Available at: htt p s://w w w.alianzaamericas..Note: All hyperlinks are active as of 3 May 2025.5 AMBROSIUS, Christian. Deportations and the Roots of Gang Violence in Central America. School of Business & Economics. Discussion Paper, Berlin, 12/2018. Available at: https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/fub188/22554/discpa p er2018_12.6 AMERICAN IMMIGRATION COUNCIL. A Guide to the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), update 2025. Available at: https://www.am e ricanimmigrationcouncil.7 MARÍN, Rossana. "El Departamento de Seguridad Nacional de EE. UU. restableció el programa migratorio 'Quédate en México'", INFOBAE. 22/1/2025. Available at: https://www.infobae.com/estados-unidos/2025/01/21/el-departamento-de-seguridad-nacional-de-eeuu-restablecio-el-prog r8 RIVERA, Fernanda. "México se opone al regreso del programa 'Quédate en México'", Meganoticias. 20/1/25. Available at: https://www.m e ganoticias.mx/cdmx/noticia/mexico-se-opone-al-regreso-del-programa-quedate-en-mexico/587032.9 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH. The 'Migrant Protection Protocols' and Human Rights Violations in Mexico. Special Report, 2020. Available at: https:// w w w.hrw.10 INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS. Precautionary Measures on the "Stay in Mexico" Programme. 2025. Available at: https://www . oas.org/en /11 CAMHAJI, Elías. "México aguarda con preocupación la avalancha de decretos migratorios de Trump", El País. 20/1/25. Available at: https:// e lp ais.com/mexico/2025-01-20/mexico-aguarda-con-preocupacion-la-avalancha-de-decretos-migratorios-de-trump.12 The concept of a "safe third country" originates from the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, signed in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1951. According to this convention, when a person applies for asylum in one country, that country can refer him or her to another country that offers the same guarantees of protection. However, goodwill is not enough; the receiving country must meet certain requirements to be considered "safe".13 REFUGEES INTERNATIONAL. Deportation with stopover: Failure of the protection measures established by the Cooperation Agreement on Asylum signed between the United States and Guatemala. 10/6/20. Available at: https://www.refugeesinternational.org/report s -briefs/deportacion-con-escala-fracaso-de-las14 EL MUNDO NEWSPAPER. US and El Salvador finalise 'unprecedented' asylum agreement: Bukele". 3/2/2025. Available at: https://diario.elmundo.sv/politica/eeuu-y-el-sa l15 BBC NEWS MUNDO. "Bukele agrees with US to accept deportees of other nationalities, including 'dangerous criminals' in prison". 4/2/25. Available at: https://ww w .bbc.com/mundo/ a16 REFUGEES INTERNATIONAL. Migration outsourcing: new agreements under analysis with Haiti, Dominican Republic and Colombia. Special report, March 2025.17 RANRUN.ES. "International civil society denounces that externalising the US border will not stop migrants".11/4/25. Available at: https://run r un.es/noticias/501342/sociedad-civil-civil-sociedad-civil-internacional-denuncian-que-externalizar-la-frontera-ee –18 U. S. CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION SERVICES. Credible Fear Screening and Interview Process, update 2025. Available at: http s ://www.usci s .19 GILBERTO BOSQUES CENTRE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES. "La política migratoria de EE. UU. y su impacto en América Latina", Informe Especial. April 2025. Available at: https:/ / www.gob.mx/sre/acciones-y-programas/centro-de-estudios-internacionales-gilberto-bosques20 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL. "The United States: A Migration System that Criminalises. Report 2025. Available at: https://www.amnesty . o rg/en/latest21 ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union). Police-ICE collaboration under the 287(g) program. Analysis paper updated in 2025. Available at: https:// w ww.a c lu.22 PIEMONTESE, Antonio. "'Alien Enemies Act', what the 1798 law invoked by Trump to repatriate alleged Venezuelan gang members says". WIRED. 10/3/25. Available at: htt p s://en.wired. dice-la-ley-de-1798-invocada-por-trump-para-repatriar-a-supuestos-pandilleros-venezolanos.23 THE REPUBLIC. "Trump denies signing proclamation invoking the Alien Enemies Act to deport Venezuelan migrants". 22/3/25. Available at: https://larepublica.pe/mundo/2025/03/22/donald-trump-niega-haber-firmado-la-proclamacion-invocando-la-ley-de-enem i24 Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is a US humanitarian programme that grants protection to nationals of countries affected by armed conflict, natural disasters or other extraordinary circumstances.25 INFOBAE. "US civil organisations question the deportation of Venezuelans". 17/3/25. Available at: https://www.infobae.com/america/agenc i.26 CNN. "Several federal judges issued orders to temporarily halt the deportations and require judicial hearings before any removals. But despite the judicial restraints, the Administration continued the deportations." 9/4/25. Available at: https://cnnesp a nol.cnn.com/2025/04/09/eeuu/judges-block-deportations-some-people-read-foreign-enemies e27 TELEMUNDO. The U.S. quintuples its deportations this year and considers more and more migrants as inadmissible". 17/9/23. Available at: www.telemundo.com/noticias/noticias-telemundo/inmigracion/estados-unidos-ha-deportado-a-mas-de-380000-personas-en-los-ultimos - si-rc n28 EL PAÍS. "Bukele opens the CECOT mega-prison to deportations from the USA". 7/2/25. Available at: https://elpais.com/internacional/2025-02-07/bu k ele-abre-el-mega p risiones-del-cecot-a-deportados-de-eeuu..29 EL PAÍS. "Bukele's mega-prison, symbol of his war against the gangs, arouses international alarm". 23/3/23. Available at: https://elpais .30 MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT. Satellite States: The Prison Externalisation of Migration in Central America, n.º 54. 2025, pp. 45-63.31 LAS AMÉRICAS NEWSPAPER. "El Salvador defends the deportation of Venezuelans from the USA and links them to organised crime". 19/3/25. Available in: http s :32 NEWSWEEK, El Salvador. "Venezuela says sending US migrants to Salvadoran jail is "crime against humanity"". 18/3/25. Available at: https://newsweekespanol.com/elsalvador/2025/03/18/v e nezuela-dice-que-envio-de-migrantes –33 EL PAÍS. "Trump fills the White House gardens with photos of arrested immigrants to celebrate his first 100 days". 29/4/25. Available at: https://elp a is.com/us/immigracion/2025-04-28/trump-llena-los-jardines-de-la-casa-blanca-de-fotos-de-inmigrantes-arrestados-para-c e lebrar-sus-primeros-100-dias..34 COLOMÉ, Carla Gloria. "El gobierno de Trump celebra el aumento de las autodeportaciones: "Estamos viendo niveles altísimos de migración inversa", El País. 2/4/25. Available at: https://elpais.com/us/migracion/2025-04-02/el-gobierno-de-trump-celebra-el-aumento-de-las-autodeportaciones-e s tam o s-viendo-niveles-altisimos-de-migracion-inversa.html.35 COL, Devan. "Indictment against Wiscosin judge underscores Trump administration's aggressive approach to immigration enforcement", CNN USA 25/4/25. Available at: https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2025/04/25/eeuu / indictment-j u eza-wisconsin-aggressive-approach-trump-immigration-trax-law.36 Trump v. J.G.G. is the tentative name used by some media and legal documents to refer to a recent and significant court case before the U.S. Supreme Court in April 2025. The case pits the federal government, led by the Donald Trump Administration, against a migrant identified by his initials J.G.G., in protection of his identity, as is customary in immigration and human rights proceedings.37 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Trump v. J.G.G. Opinion of the Court, April 2025. Available at: https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/20 2 5/tr ump_ v _jgg.html (accessed 28 April 2025).38 CNN EN ESPAÑOL. "La República Dominicana deportó en 2024 a 276.000 haitianos". 2/1/25. Available at: https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2025/01/02/latinoame r ic a39 TELEMUNDO NOTICIAS. "Dominican Republic intensifies deportations of Haitians: 10,000 per week". 12/12/2024. Available at: https://www.telemundo.com/noticias/noticias-telemundo/internacional/republica-dominicana-deportaciones-masivas- h aitianos-10000-una-semana-r40 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL. "Deportations of pregnant women in the Dominican Republic". November 2024. Available at: https: / /www.a m nesty.org/en/documents/amr27/8597/2024/en/ "Statement on mass deportations in the Dominican Republic". November 2024. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/es/documents/amr27/8597/2024 /