Trump II and US Nuclear Assurances in the Indo-Pacific

by Liviu Horovitz , Elisabeth Suh

한국어로 읽기Leer en españolIn Deutsch lesen

Gap

اقرأ بالعربيةLire en françaisЧитать на русском

Why Australia, Japan, and South Korea Have Other Concerns

While heated debates in Europe have focused on how to respond if Donald J. Trump is re-elected to the White House, discussions in Australia, Japan, and South Korea reveal a greater sense of confidence in Washington’s commitments. The fear that the United States would withdraw its nuclear assurances is much less pronounced in the Indo-Pacific than in Europe. This serenity appears primarily grounded in a shared understanding that a bipartisan consensus is driving the US commitment to contain China’s rise – a goal that requires reliable allies across the Pacific. At the same time, US allies want to maintain the regional status quo and are willing to support Washington’s efforts. Trump’s potential return does little to change these structural incentives. Instead, Pacific allies fear challenges to the East Asian regional order, challenges that are also relevant for Europe’s security and prosperity.

European and Pacific US allies share similar concerns about a potential second Trump administration: allies everywhere fear that Trump would once again pursue a transactional approach to US foreign policy. Disputes between allies would play out in public, unsettling domestic populations, delighting adversaries, and endangering the perceived credibility of the common defence policy. Given Trump’s penchant for cosying up to autocrats, both European and Pacific allies worry that Washington will either trade away key shared interests to extract questionable concessions from dictators or, if negotiations fail (again), that Trump will drag them into unwanted conflicts.

However, beyond these shared concerns, policymakers in Canberra, Seoul, and Tokyo seem to be more confident. They believe they know how to manage Trump’s ego and can offer him lucrative deals. Furthermore, they assume that a second Trump administration will remain engaged in the Western Pacific, necessitating the presence of reliable partners to maintain influence and contain China. These assumptions do not lead to fewer concerns, but to less fundamental concerns in trans-Pacific relations. However, European allies express fear that Trump may seek to undermine or even terminate NATO, which would result in the withdrawal of US nuclear assurances. Even in South Korea, public debate about its own nuclear weapons is primarily focused on the perceived threat from North Korea, rather than on concerns within the alliance.

It is primarily the changed regional balance of power and China’s ambitions that worry the trans-Pacific allies. On the one hand, the extensive competition between the US and China gives rise to the expectation that Washington will remain engaged and that the security relationship and extended nuclear deterrent in the Pacific will remain stable. On the other hand, this competition demonstrates to Pacific allies that the actions of the current and subsequent US administrations will have a decisive impact on the evolution of the balance of power and the regional constellation in the decades to come. There is therefore concern that a transactional second Trump administration could undermine protracted joint efforts to maintain order, laying the groundwork for eventual Chinese dominance in this strategically important region.

A changing military balance of power

Regional and global economic, political, and technological developments are shifting the balance of power in the Asia-Pacific region in very different ways than in Europe. After all, the starting position is completely different: Russia’s economy is only one-tenth the size of the EU’s, and Europe lacks political resolve and operational military capabilities rather than resources per se. The critical questions are whether the United States would defend Europe in a geographically limited crisis, whether the Western European nations would go to war for their Eastern European allies, and whether the current forces are adequate to deter or repel Russian aggression.

In contrast, China’s economy is almost two and a half times larger than the combined economies of Australia, Japan, and South Korea – a difference that roughly mirrors the disparity in military spending. While Europeans have consciously delegated their security to Washington, US allies in the Western Pacific have limited options for developing their own conventional capabilities to counterbalance China.

Hence, the US allies are primarily concerned with China’s determination to reshape regional dynamics. Under Xi Jinping, Beijing has pursued a more confrontational foreign policy designed to advance China’s regional interests and diminish, if not eliminate, US influence across the Pacific. China has proved willing to underpin its combative diplomacy through both costly economic measures and the rapid modernisation of its armed forces. It is still assumed that the US will continue to play the leading military role for the time being, as Washington retains superiority in conventional and nuclear capabilities as well as in many other areas. However, China is rapidly catching up and asserting its regional claims, making it increasingly difficult for the United States to effectively project power so far from its own shores. This is why allies fear that China could dominate the Asia-Pacific region in future.

Against this backdrop, many see Taiwan’s future as the harbinger of the region’s possible development. If Beijing were to control this central component of the first island chain, it would gain both military and political leverage over the East and South China Seas – both of which are strategically important. To signal its resolve, Beijing frequently conducts demonstrations of military power such as in the airspace separating the mainland from Taiwan. The trans-Pacific allies suspect that China could (soon) leverage both conventional and nuclear capabilities to present them with a fait accompli, thus gaining control over Taipei before the US could intervene. This would also damage Washington’s credibility as the guardian of regional order. Whether Beijing would indeed wage war against the United States over Taiwan, or whether it merely seeks to alter the military balance of power by exposing Washington, Taipei, and regional US allies to unacceptable escalation risks remains unclear – but the very fact that China keeps its intentions ambiguous raises worst-case fears.

Nuclear threats

In recent years, Beijing has been engaged in a major expansion of its nuclear arsenal. According to US forecasts, China could double the number of its nuclear warheads from the current estimate of 500 nuclear warheads by 2030. While Russia and the United States would still dwarf China’s nuclear forces numerically, Beijing appears to be aiming for the same qualitative league of strategic nuclear weapons systems as possessed by Washington and Moscow. The exact motives behind China’s nuclear build-up remain controversial. Yet the types of weapons and the pace of their development suggest that Beijing would at least like to weaken Washington’s escalation dominance in a crisis. Such developments could theoretically strengthen the mutual nuclear deterrent between China and the US. On the one hand, it could reduce the risk of a global war. On the other hand, for Washington’s Pacific allies this means that their protective power could no longer credibly threaten nuclear escalation and effectively deter Beijing. As a result, they would be outgunned in a conventional war with China.

North Korea’s foreign policy, coupled with its nuclear build-up is a further cause for concern. According to estimates, Pyongyang could currently have 90 nuclear warheads at most at its disposal. However, it has significantly diversified its delivery systems. North Korea emphasizes a nuclear doctrine with which it could drive a wedge between the Pacific allies by threatening South Korea with tactical nuclear strikes and the US with strategic nuclear strikes. In addition, Washington and its allies perceive North Korea’s threshold for using nuclear weapons to be very low, as they assume that Pyongyang is also trying to deter conventional attacks in this way.

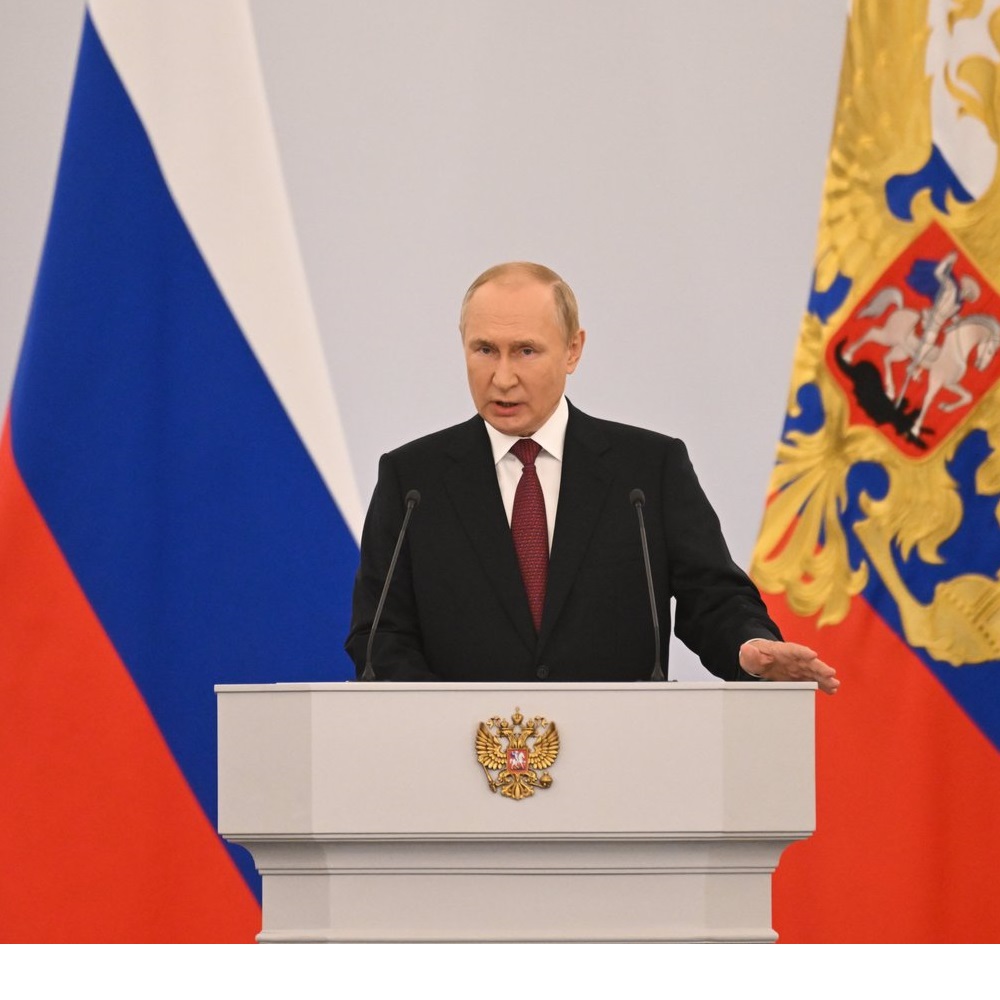

Finally, the policy changes Moscow has implemented are intensifying regional concerns with respect to the future behaviour of China and North Korea. Russia maintains important military facilities in North-East Asia, militarises the Kuril Islands, and conducts strategic air and naval patrols with China across the Western Pacific. Moscow’s focus, however, is clearly on Europe. Nevertheless, Australia, Japan, and South Korea fear the concrete consequences of Russia’s cooperation with Beijing and Pyongyang. It is clear that this cooperation fuels Moscow’s war in Ukraine. In the worst-case scenario, closer military cooperation could result in more coordination and opportunistic behaviour to exploit each other’s conflicts or challenge the US and its allies with additional crises. What is more likely, however, is not a trilateral front, but a triangular dynamic that remains susceptible to mistrust, power calculations, and priority setting by the respective rulers – and which can nonetheless boost existing challenges to regional security and non-proliferation. Moreover, the outcome of Moscow’s ongoing war of aggression in Ukraine could set risky precedents for revisionist agendas in East Asia. At this point, China and North Korea could learn from Russia’s nuclear rhetoric how allies can be unsettled and deterred from going “too far” in supporting Ukraine.

Converging interests and (radical) alternatives

The challenges in the Asia-Pacific region could have a more serious impact on the regional and global order than the conflicts in Europe. They are therefore already influencing the balance of interests and thus the room for manoeuvre of the actors involved.

First, there is a bipartisan consensus in Washington that American influence in the Pacific must be preserved. Most see the larger Indo-Pacific as the strategic centre of gravity, perceive US influence in the region as key to sustaining America’s preeminent position in international relations, and conclude that containing China is a must. Thus, even in a highly partisan political environment, the status of Taiwan and its treaty alliances with Australia, Japan, and South Korea remain essentially of unquestioned importance to the United States.

Second, Washington needs its allies in the Western Pacific. As the military gap with China narrows, the US military must rely on the critical bases, logistical support, and complementary capabilities of regional allies. Consequently, Australia, Japan and South Korea host significant US military forces, facilitating rapid deployment and sustained operations in the region. The US is not only seeking to strengthen bilateral security cooperation and can also work with Australia and Japan as indispensable partners for regional formats – such as the Quad that includes India – to pool resources to contain Beijing’s ambitions. Conversely, given China’s considerable economic power, any attempt to constrain its technological or financial capabilities requires wide-ranging cooperation. It is thus unsurprising that the Biden administration has actively sought to garner support across the Indo-Pacific region to foster economic partnerships, supply chain resilience, technology transfers and research collaborations.

Third, allies in the Western Pacific are prepared to contribute to more effective military action. Many European governments, on the other hand, take US security measures for granted and are reluctant to divert funds from social and other purposes to their armed forces. Australia, Japan, and South Korea each have extensive trade relations with China, having tied their prosperity to Beijing. To ensure that this beneficial balance can be maintained, Canberra, Tokyo, and Seoul have reliably invested in allied deterrence and defence. Australia and South Korea have done and continue to do so, even under governments that are more sceptical about relations with Washington.

Fourth, although US allies in the Western Pacific greatly benefit from the current strategic arrangements, they have alternative (even if not attractive) options available – and Washington is acutely aware of this reality. On the one hand, policymakers in Washington suspect that if mistrust of US commitment were to reach an intolerable level, its Pacific allies might decide to bandwagon with China. As Australia has no territorial dispute with Beijing, and Japan and South Korea have only one limited territorial dispute respectively with China, their concerns are more economic and political in nature. A different regional architecture, though significantly less attractive, would not directly threaten their fundamental interests and, therefore, would probably be tolerable. On the other hand, Japan and South Korea have the technical capabilities and sufficiently limited regional institutional ties – in Seoul also significant domestic political support – to constrain China’s coercive capabilities by acquiring their own nuclear weapons. In the absence of US reassurance, they could combine the two alternatives and side with Beijing from behind their own nuclear shield.

Given these four fundamentals, there is relative confidence in Canberra, Tokyo, and Seoul that the US will continue with its security architecture in – and therefore with its extended nuclear deterrent for – the Western Pacific, whether or not Donald Trump wins the 2024 presidential election. Moreover, both Trump and his supporters have repeatedly struck a confrontational tone toward China, emphasising their willingness to increase US power projection through military means.

Counter-balancing by the United States and its allies

Amid a shifting politico-military landscape and aligned US and allied interests in preserving the status quo, a concerted effort to counterbalance China’s military expansion is evident. These efforts are extremely expensive. The sunk costs of this effort strongly suggest to all concerned that, regardless of who occupies the White House, the major strategic question facing the future administration will likely be how to effectively contain China while both maintaining strategic deterrence against Russia and avoiding the escalation of potential crises. For now, the United States seems to pursue a four-pronged strategy that involves developing additional nuclear capabilities, building up conventional options, enhancing allies’ capabilities, and expanding security cooperation.

First, planners and pundits in Washington are assessing how to make better use of US nuclear options. While a major nuclear modernisation effort is underway, a growing number of experts and politicians have concluded that the US arsenal needs to be expanded. In addition, the legislative branch has been pushing the Pentagon to pursue additional nuclear options, such as a nuclear-armed cruise missile (SLCM-N). The Trump administration already called for this in 2018 and would likely continue to pursue it, if it returns to power. Moreover, some in the hawkish Republican camp are even calling for the first use of such low-yield nuclear weapons to be considered in order to offset China’s operational advantages and prevent an invasion of Taiwan – but it is unclear how much weight such voices could carry in a second Trump term.

Second, and more importantly, the US government is building up its conventional capabilities. Although many Democrats criticised the Trump administration’s 2019 decision to abandon the legal prohibition on deploying intermediate-range missiles, the Biden administration has pursued this same course. As a result, US armed forces will soon be deploying such missile systems to their European and Pacific bases; a planned relocation to the US base in Wiesbaden was recently announced. For Asia, it has already been announced that the Dark Eagle hypersonic system will be fielded on Guam. In order to equalise the conventional balance of power with China, however, the various other US medium-range systems would have to be stationed on allies’ territory. Given the high probability that Beijing would respond with harsh economic retaliation, it remains unclear whether – or under what conditions – Canberra, Tokyo, or Seoul would agree to such deployments.

Third, the US government has been working with its allies in the region to improve their own military capabilities. First, Australia, Japan, and South Korea continue to develop their national capabilities, particularly where long-range strike capabilities and strategic naval assets are concerned. Second, the US government seeks to strengthen its allies’ early warning and missile defence capabilities. It is especially relevant that Washington appears to have shifted its position to weigh deterrence challenges more heavily than proliferation concerns. Indicative of this is the unprecedented technology transfer involved in providing Australia with stealthy nuclear-powered submarines. This transfer requires an unparalleled level of verification to make it transparent that Canberra does not divert some of the highly enriched uranium needed for submarine propulsion to build its own nuclear weapons. Another example is the US decision from 2021 to lift all restrictions that had long been placed on South Korea’s missile development programs. Equally important is the widespread sale of Tomahawk cruise missiles in recent years, including to Australia and Japan.

Finally, while bilateral alliances with Washington continue to be characterised by patron-client relationships, Washington appears committed to empowering regional powers not only by helping enhance their capabilities, but also by expanding security cooperation and allies’ roles therein. For instance, the Biden administration wants Japanese shipyards to regularly overhaul US warships, which allows for their constant presence in East Asia. It also upgraded bilateral consultations which carve out a South Korean role in US nuclear operations. Further, it is pursuing technology transfers in advanced military capabilities that will buttress Australia’s strategic reach. Although these alliance initiatives bear the hallmarks of the Biden administration, they fit the “burden-sharing while preserving influence” mantra. This tactic characterised Trump’s term in office and is currently aspired to by broad segments of the Republican Party. Thus, while officials and experts in Australia, Japan, and South Korea expect communication and coordination mishaps, procedural quibbles, funding challenges, and implementation delays, these individuals strongly believe that bipartisan US support for these measures will remain strong.

Nevertheless, concerns abound

Although some of Trump’s domestic supporters would welcome any reduction in US commitments abroad, a second administration would have to face the reality that abandoning extended nuclear deterrence remains fundamentally at odds with its primary goals. Abandoned by their long-time protector and facing massive threats, former allies would likely seek to appease China, and could acquire nuclear arsenals independently. Such developments would run counter to the interests of any US administration, including a Trump White House. Fears of nuclear abandonment are therefore not the dominant concern, leaving plenty of room for allies’ other worries.

The Pacific allies invest relatively heavily in national and joint deterrence, and defence. But they are also worried about Trump’s penchant for pressuring allies to make concessions. Most in Seoul, for example, expect at least a repeat of the tough cost-sharing negotiations of the first term. Trump and his supporters have been vocal about demanding increased financial contributions from Seoul for the US troops stationed on the Korean Peninsula, frequently coupled with threats to withdraw some or all of those forces, references to the trade imbalance, and downplaying the threats posed by North Korea. Congressional support ensures the presence of US soldiers, but the White House has considerable leeway in determining the size and mandate of these deployments – and many expect Trump to use security commitments to extract economic concessions from allies. Conversely, some in Canberra and Tokyo worry that a Trump administration would seek to renegotiate various military procurement agreements to shore up US financial gains – but few believe that existing agreements would be revoked in the course of such disputes.

Another fear in Australia, Japan, and South Korea is that a second Trump administration will reduce or abandon the Biden White House’s various regional security cooperation initiatives and want all relations to again go through Washington first. On the one hand, Trump and his advisers may be pleased with the burden-sharing benefits associated with these new forms of cooperation and continue to pursue them. On the other hand, a GOP-led administration might seek a return to the traditional centralising “hub-and-spokes” system in order to exert more control over allies. The allies therefore fear that without US leadership, these intergovernmental initiatives are likely to stagnate, and competition among protégés for the attention of the common patron will be reignited. This might apply particularly to the very practical, but politically sensitive, trilateral partnership between Japan, South Korea and the United States.

Less pronounced than the aforementioned fears are concerns about Trump’s “deal-making” tendencies, such as being abandoned in a costly crisis or entangled in a regional conflict. Ambiguity surrounding Trump’s policies vis-à-vis China, North Korea and Russia reflect general uncertainties about future developments in Europe and East Asia as well as Trump-specific inconsistencies. With regard to China, most expect confrontational security and economic policies, while a few fear that Trump will seek a grand bargain with Xi. Trump has kept his stance on the status of Taiwan ambiguous: he could either reject all support for Taiwan or, if faced with Chinese intransigence, decide to explicitly commit to defending Taipei. While the former would expose US allies to potential Chinese coercion, the latter could lead to an open military conflict with Beijing – and many allies do not trust Trump’s resolve in such a crisis. Regarding North Korea, most hope that Trump’s failed summitry with Kim Jong Un served as a sufficient lesson. However, some worry he may seek to prove that personal relationships facilitate agreements that would otherwise be difficult to achieve. For example, he could again try to persuade Kim Jong Un to stop his nuclear build-up by offering economic incentives (thus effectively breaking sanctions). As a quid pro quo for Seoul, Trump could go so far as to quietly accept South Korean nuclear proliferation. Finally, concerning Russia, many fear that Trump might propose a deal to Putin to freeze the conflict in Ukraine, an approach from which Xi could draw conclusions for revisionism in East Asia.

Implications for Europe

As Trump is prone to miscalculations and erratic behaviour, caution is required when trying to predict his future policy after re-election. Nevertheless, it is important to understand why Australia, Japan, and South Korea are less concerned about US nuclear assurances. Three conclusions can be drawn from this analysis for Europe.

First, even if Trump is re-elected, fundamental changes in Washington’s relations with its Pacific allies are unlikely – which is good news for Europe. For one thing, European economic success depends on the absence of open conflict between China and the US. For another, stable relations in the Asia-Pacific are indirectly a boon to NATO, since US security provision in Europe is heavily dependent upon the success of its more important commitments across the Pacific. Nevertheless, considerable uncertainties remain due to structural challenges as well as Trump’s political agenda and personal idiosyncrasies. However, the pressure from Washington on Europe to adapt its China policy is likely to increase under a second Trump administration, especially as it is likely to be almost exclusively composed of China hardliners (China hawks).

Second, in the face of these risks, Europeans should recognise that Washington and the Pacific allies will expect economic-political rather than military contributions from Europe. It would therefore be advantageous if European governments could use their weight within the global economic system to support the US in containing China’s military expansion. If Europe now helps to influence Beijing’s technological and financial capabilities, it could imply European willingness to impose sanctions on China in the event of war. This would also send a strong signal against revisionism in East Asia. Given Trump’s unpredictability, steps that seem costly today may prove worthwhile in retrospect if regional stability in Asia is severely damaged.

Last but not least, one valuable lesson can be gleaned from understanding why US allies in Asia hold more optimistic expectations about a potential second Trump administration. Ultimately, the source of their optimism lies in Washington’s dependence on its allies and their readiness to take on greater responsibility. Arguably, this particular equation is primarily a result of exogenous factors – such as the region’s strategic importance und China’s ambitions. But it should also now be clear to Europe’s decision-makers, experts and public that the more they invest in their own capabilities to influence regional security policy, the less they will have to worry about Washington’s vacillations.

Dr Liviu Horovitz and Elisabeth Suh are researchers in the International Security Research Division. This paper is published as part of the Strategic Threat Analysis and Nuclear (Dis-)Order (STAND) project.