Cyber Diplomacy and the Rise of the 'Global South'

by André Barrinha , Arindrajit Basu

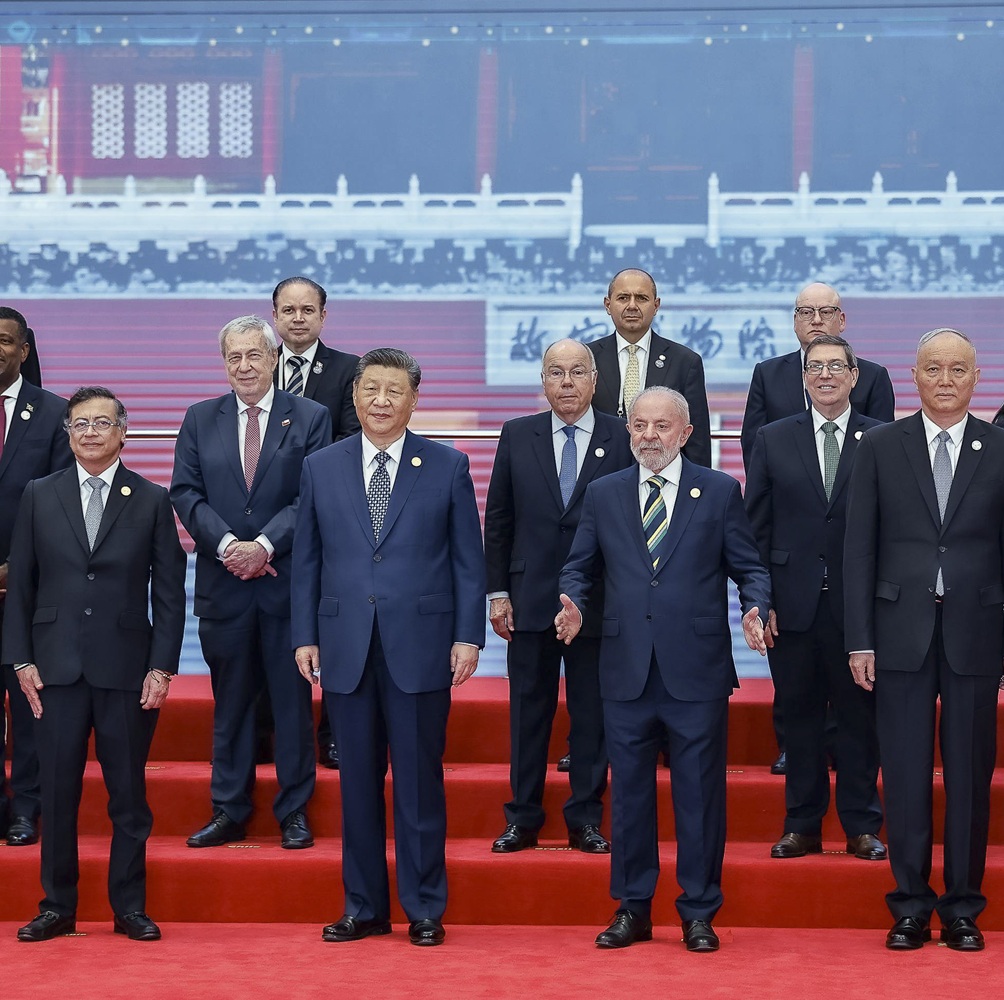

한국어로 읽기 Leer en español In Deutsch lesen Gap اقرأ بالعربية Lire en français Читать на русском On September 24, 2024, speaking from the gargantuan Kazan International Exhibition Centre during the BRICS Summit in Russia, Chinese President Xi Jinping emphatically extolled the “collective rise of the Global South [as] a distinctive feature of the great transformation across the world.” While celebrating “Global South countries marching together toward modernization [as] monumental in world history and unprecedented in human civilization,” the Chinese leader hastened to add that China was not quite a part of but at the Global South’s “forefront”; that “will always keep the Global South in [their] heart, and maintain [their]roots in the Global South. As emerging powers in the BRICS+ grouping thronged Kazan in a clear sign to the West that they would not unwittingly entrench Vladimir Putin’s full-scale diplomatic isolation, China’s message was clear: as a great power, they would not ignore or undermine the interests of the Global South. The rise of the Global South as a central voice in world politics concurs with the emergence of cyber diplomacy as a diplomatic field. This is not a coincidence, as they are both intimately related to broader changes in the international order, away from a US-led liberal international order, toward a post-liberal one, whose contours are still being defined, but where informal groupings, such as the BRICS+ play a key role. One could even argue that it is this transition to a new order that has pushed states to engage diplomatically on issues around cyberspace. What was once the purview of the Global North, and particularly the US, is now a contested domain of international activity. In this text we explore how the Global South has entered this contestation, and how it articulates its ever-growing presence in shaping the agenda of this domain. However, as cyber diplomacy is mainstreamed across the Global South, it is unclear whether it will continue to be a relevant collective force in forging the rules and norms that govern cyberspace, or whether the tendency will be for each country to trace their own path in service of their independent national interests. The evolution of cyber diplomacy in a post-liberal world Cyber diplomacy is very recent. One could argue that its practice only really started in the late 1990s, with Russia’s proposal of an international treaty to ban electronic and information weapons. Cyber diplomacy, as “the use of diplomatic resources and the performance of diplomatic functions to secure national interests with regard to the cyberspace” (or more simply, to the “the application of diplomacy to cyberspace” is even more recent, with the first few writings on the topic emerging only in the last 15 years. To be sure, the internet was born at the zenith of the US-led liberal international order and was viewed as an ideal tool to promote based on liberalism, free trade and information exchange with limited government intervention and democratic ideals. Cyber libertarians extolled the virtues of an independent cyberspace, free from state control and western governments, particularly the US, did not disagree. They viewed the internet as the perfect tool for promoting US global power and maintaining liberal hegemony -“ruling the airwaves as Great Britain once ruled the seas.” The internet was ensconced in the relatively uncontested unipolar geopolitical moment. As the pipe dreams of a liberal cyberspace began to unravel with China and Russia pushing for an alternate state-centric vision of cyberspace, cyber diplomacy began to emerge both as a “response to and continuing factor in the continuing battle in and over cyberspace.” Explicitly, we can pin down its origin to two factors. First, is the perception that cyberspace was becoming an increasingly intertwined with geopolitics and geo-economics, with states starting to better understand its threats, but also its opportunities. Moonlight Maze, the 2007 attacks against Estonia or even Stuxnet were all cases that helped focus the mind of policymakers around the world. Second, the broader context of underlying changes in the international order necessitated cyber diplomacy as a bridge-building activity both to mitigate great power rivalry and to preserve the stability of cyberspace and the digital economy. Private companies, till then the beneficiaries of an open and de-regulated internet, also had to step in to ensure that their own interests and profit motives were safeguarded. These two intertwined factors dominated the discussions around cyber diplomacy for most of the 2000s. Initially, the predominant focus was arms control, reflected in the composition of the first few Group of Governmental Experts (GGE) iterations, the forum created by the UN General Assembly (UNGA) to discuss the role of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in international security. And although experts appointed by countries from the Global South were present since the first meeting in July 2004 the debate was very much framed as a discussion among great powers. As discussions progressed, and the GGE became a process in itself, some states outside the permanent members’ group started to engage more actively. This also coincided with the progressive creation of cyber diplomacy posts and offices in foreign ministries around the world. The field was becoming more professional, as more states started to realise that these were discussions that mattered beyond the restrictive group of power politics. Countries such as South Africa, Brazil, or Kenya started to push for the discussion of issues that affected a larger group of states, with a particular focus on cyber capacity building not just at the UN-GGE but also at other multilateral and multi-stakeholder processes and conferences including the World Summit on Information Society (WSIS), Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), Internet Governance Forum (IGF) and the International Telecommunications Union (ITU). The creation of a new Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) at the UN First Committee (after an acrimonious diplomatic process) had an important effect in the diversification and democratisation of the discussions, as these were now open to the whole UN membership, and non-state actors were given the opportunity to observe and participate in these sessions. Further, in 2022, the UN set up an Ad Hoc Committee (AHC) to negotiate a cybercrime convention (adopted by consensus by UNGA members in December 2024) that also enabled all UN members to participate in the negotiations. The opening up of these processes exposed many states, particularly in the Global South, to the field, and it forced them to actively engage in discussions that until recently were seen as the dominion of great powers. The African Group and the G77 were now able to actively participate in the discussions, with frequent statements and contributions. Conceptualising the Global South in cyber diplomacy As cyber diplomacy progressed, policy-maker and academics alike understood global cyber governance to be divided along three main blocs of states. The status quo defenders were led by the US and (mostly Western) like-minded states, focused on the promotion of liberal values and non-binding norms shaped by a multi-stakeholder approach and adherence to existing tenets of international law but resisted significant changes in the governance of cyberspace. A revisionist group, led by Russia and China, advocated for a new binding international treaty and multilateral governance with the objective of guaranteeing security and order rather than necessarily promoting liberal values. Given this impasse, the role and influence of a group of states termed ‘swing states’ or ‘digital deciders’ has been recognized as critical to determining the future of cyberspace, most prominently in a detailed 2018 report by the Washington DC-based think-tank New America . This grouping that largely includes emerging powers from the Global South including India, Indonesia, Brazil, Mexico and South Africa, are understood as countries that are yet to “gravitate towards either end of the spectrum, some undecided and others seeking a third path.” Given these groupings, it is worth considering how the Global South fits in with present conceptualisations of cyber diplomacy, or whether it is a grouping at all. The term ‘Global South’ has come in for some criticism given the heterogeneity of countries it describes and its geographical inaccuracy (many Global South countries are not quite in the geographical South.) To be fair, the term never aspired for terminological accuracy and was instead coined to conceptually represent a group of countries during the Vietnam dissatisfied with the political and economic exploitation from the Global North. In that regard, Global South is a “mood,” a metaphor for developing countries aiming to find their way in an increasingly contested world. The war in Ukraine only augmented these fissures as the West were confounded by the Global South’s refusal to take a stand against brazen Russian aggression in Europe. The developing world saw it differently though: in an international order long-built on racism and inequality, expecting these countries to take a stand in their “petty squabbles” while they had also carried out “similarly violent, unjust, and undemocratic interventions—from Vietnam to Iraq” was a bridge too far. The Ukraine war helped clarify the combination of behaviours that countries within the Global South exhibit to attain this strategic goal: ideological agnosticism or neutrality; selective engagement with norms and rules; and finally, multi-pronged bilateral and minilateral groupings, with equidistance from the major powers. These three approaches helped illuminate the multiple different forms of agency that each developing country exercises vis-à-vis the international order based on their own interests and quest for strategic autonomy. However, what became evident as Russians bombs started to fall on the street of Kyiv, was already visible in these states’ interactions in cyber diplomacy. First, much of the Global South has refused to take an explicit stand on the controversial fissures that the leading powers have spent much of their time debating, including whether cyberspace governance should be state-centric or driven by new rules or existing international law. Throughout the negotiating processes at the UN OEWG and AHC, as Russia and China clashed with the United States and its allies on the text of several controversial proposals, most developing countries took an agnostic approach, neither explicitly endorsing or opposing any of these potential treaty provisions. (There are naturally some exceptions: an analysis of voting patterns suggests that Iran and North Korea have firmly pegged themselves to the Russian and Chinese side of the aisle whereas some smaller developing countries have gravitated towards the US side of the aisle.) Second, there has been selective engagement when security or developmental interests are directly impacted. For example, in its joint submission to the UN’s Global Digital Compact (GDC), the G77+China asserted the need for equitable cross-border data flows that maximize development gains. The GDC is the UN’s first comprehensive framework for global digital cooperation. Long concerned about the misuse of the multi-stakeholder model by private actors for profit at the expense of developmental interests, the G77 also highlighted the need for “multilateral and transparent approaches to digital governance to facilitate a more just, equitable and effective governance system.” Finally, countries in the Global South have entered into multiple technology partnerships across political and ideological divides. US efforts at restricting the encroachment of Chinese hardware providers like Huawei and ZTE into the core technological periphery of several Global South countries using allegations of surveillance were sometimes rebuked, given the Five Eyes’ proclivity and reputation for also conducting similar surveillance, including on top officials. By being agnostic on controversial ideological issues, countries in the Global South have been able to maintain ties with great powers on all sides of the political spectrum and foster pragmatic technological partnerships. Will the Global South rise? The Global South’s rise as a potent force in cyber diplomacy will, however, depend on three factors. Can it maintain ideological consistency on developmental and rights concerns, including on how the internet is governed at home? Can they continue to work with multiple partners without succumbing to pressure either from Washington or Beijing? Will emerging powers in the Global South (like India, Brazil and Indonesia) bat for the interests of the larger developing world, rather than simply orchestrating global governance to service their own interests or that of the regime in power? Given that cyber diplomacy emerged and developed as the playground of great powers, analysing it through the perspective of the Global South enables us to focus on cyber governance as an issue that goes beyond (cyber)security concerns – including economic development and identity (cutting across issues of race, gender, and colonialism) – and to see the world from a perspective that goes beyond the dynamics of great power competition. Analytically, it is useful to understand how these states position themselves and justify their actions on behalf of the whole. When looking inside the box, we see some collective movement but also a desire on part of the great powers, including China to incentivise the developing world to see the world as they do. The Global South remains relevant as a construct that captures the mood of the developing world on the geopolitics of technology of cyber issues. Its “great strength” will emerge not from swinging between Washington and Beijing or being orchestrated through New Delhi or Brasilia. It will instead come through standing their ground, in service of their own security and developmental interests in cyberspace. And as they progress, it remains to be seen whether the “Global South” retains its relevance as an analytical construct or whether it will give way to other denominations that better capture the developing world’s nuances and differences vis-à-vis the international cyber order. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC 4.0 license.