The strategic adjustments of china, india,and the us in the indo-pacific geopolitical context

by Nguyen Tuan Binh , Tran Xuan Hiep , Nguyen Dinh Co

한국어로 읽기Leer en españolIn Deutsch lesen

Gap

اقرأ بالعربيةLire en françaisЧитать на русском

Abstract: Since the beginning of the XXI century, the Indo-Pacific region has become the “focus” of strategic competition between the world‟s great powers. This area included many “choke points” on sea routes that are strategically important for the development of international trade, playing an important role in transporting oil, gas, and goods around the world from the Middle East to Australia and East Asia. The article analysed the geostrategic position of the Indo-Pacific region and the strategic adjustments in foreign affairs of some major powers in this region, specifically the US, China, and India. To achieve this goal, the authors used research methods in international relations to analyse the main issues of the study. In addition to reviewing previous scholarly research and reviews, the authors used a comparative approach to assess the interactions between theory and data. The authors believed that these data are important for accurately assessing the strategic importance of the Indo-Pacific region, and this area was an important trigger for the US, China, and India to make adjustments to its foreign policy. If the US proposed a strategy called “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP), India‟s strategy was called the Indo-Pacific Initiative. China‟s Indo-Pacific strategy was clearly expressed through the “String of Pearls” strategy and the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI). As a result, in the geopolitical context of the Indo-Pacific region, the competition between major powers (the US, China, India...) is also becoming fiercer and more complex. It has a significant impact on other countries in the region.

INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, the conception of geopolitics has not received a consensus among generations of scholars, and it tends to increase complexity in the international context after the Cold War and create different schools in the study of political science and international relations. This diversity reflects the interplay between the development of theory and the development of international political status and shows the diverse nature of international politics and international political studies.

Hans J. Morgenthau, a typical realist theorist (1948), said, “International politics, like every other kind of politics, is a power struggle. Whatever the ultimate aims of international politics, power is always the immediate aim” (p. 13). In geopolitics, this relationship is expanded into a highly complex tripartite relationship between three factors: geography - power - politics. The Britannica Dictionary defines geopolitics as “the analysis of the influence of geography on power relationships in international relations” (Deudney 2013). Geopolitics can be understood as a dialectical next step of the relationship between geography and power. Geography does not fully determine how a power interaction happens, but geography significantly affects any political analysis. It is one of the sources of hard power, but sometimes, it is the leading cause of disputes between powerful actors. Ultimately, increasing ownership of geographical factors will increase power/hard power. This is the last and perhaps the most significant factor enabling an international political actor to prevail in imposing their political will on one or more other political actors.

In past centuries, powerful Western countries consistently sought methods to expand their colonies and garrisons, aiming to control major transportation routes worldwide and exploit natural and human resources in their areas of influence or occupation. Their objective was either to maintain hegemony on a global or regional scale or to challenge and contest existing hegemony. This approach is commonly used to explain peace, conflict, competition, and development through a geopolitical lens.

Traditional German geopolitics, the birthplace of modern geopolitics, which rose during World War I and flourished under the Third Reich, was influenced by geographical determinism, especially theories that occurred in the mid-twentieth century. The German school believes that geopolitics is the study of space from the state‟s point of view. Specifically, Karl Haushofer asserted that “Geopolitics is the new national science of the state (...) a doctrine on the spatial determinism of all political processes, based on the broad foundations of geography, especially of political geography” (Cohen 2015, 15). In this way, geographical factors are believed to be objective actors that are relatively fixed in nature; the effects of geographical factors on the political policies of a country are considered intuitively cognizable through deductive methods, and their consequences to power interactions in a relevant region can be predicted accurately with the same method of thinking. However, it is more complex and ambiguous due to the diverse coexistence of geographical and non-geographical variables.

In the early XXI century, one way to understand shaping theory was not to study geography or politics but from politics to geography or a bidirectional way between two factors. Saul Bernard Cohen‟s point of view is one of the most common conceptions of the impact of geography on politics. Cohen (2003): “Geopolitics is the analysis of the interaction between, on the one hand, geographical settings and perspectives and, on the other hand, political processes. (…) Both geographical settings and political processes are dynamic, and each influence and is influenced by the other. Geopolitics addresses the consequences of this interaction” (Cohen 2015, 16). The point of view of Yves Lacoste (French geographer) represents the opposite. He noted that:

The term „geopolitics‟ is understood in a variety of ways. It refers to all things that involve the competition for power or influence over territories and the people living there, the competition between all types of political powers, which is not only countries but also political movements or secret armed groups, the competition for controlling or dominating large or small territories (Lacoste 2012, 28).

We ignore the extension of the political interaction entities, and this definition shows that “competition” between political entities plays a leading role in this idea of geopolitics. There are two points we need to expand from this conception of geopolitics. The first is the purpose of the disputes, though often the manifest purpose rather than the latent purpose is to own natural and human sources. The second is competition between political entities, which is organic interaction, like what Foucault recognizes as power. These traditional ways of studying were challenged by the School of critical geopolitics, which occurred and developed at the beginning of the XXI century.

the XXI century. According to critical geopolitics, which comes from the social structuralism approach, when experts in state administration create ideas about geographical locations, these ideas influence and underpin their political behaviour and policy choices. And these ideas affect how people process their concepts of place and politics. This tendency has led researchers to focus on analyzing geographical discourses to identify underlying assumptions about power. This aims to break the major concepts of international politics (Flint 2006; Toal 2006). The conceptual awareness of critical geopolitics has been abandoned (Fouberg et al. 2012, 535).

In this article, we maintain a unified concept of terminology. Concepts that begin with the prefix “geo” are usually theories of behaviour or policies (military, economic, politics, etc.) of one or more states through geographical, natural, or humanistic aspects rather than focusing on the influence of geographical variables only. Prefix concepts (“geo”, short for geography) should be in the politics/political science sub-disciplines rather than in geography.

THE GEOPOLITICAL IMPORTANCE OF THE INDO-PACIFIC REGION

The Indo-Pacific region is situated along the coasts of the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific Ocean, with seas connecting these two vast bodies of water. The Indo-Pacific region is home to more than half of the world‟s population and has abundant resources and strategically significant international sea lanes. It is one of the most dynamic economic regions, fostering cooperation and growth between developed and developing economies. Interestingly, the term “Indo-Pacific” is not novel but instead borrowed from the field of geo-biology, where it denotes tropical waters stretching from the western coast of the Indian Ocean to the Western Pacific Ocean. The term “Indo-Pacific” with a geopolitical connotation was first mentioned by Gurpreet S. Khurana, Director of the National Maritime Foundation in New Delhi (India). In the article “Security of Sea Lines: Prospects for India-Japan Cooperation”, published in Strategic Analysis in 2007, G. S. Khurana defined the Indo-Pacific as a maritime space connecting the Indian Ocean with the Western Pacific Ocean, bordering all countries in Asia (including West Asia, Middle East) and East Africa (Khurana 2007, 150). He argued that India and Japan‟s common and core interests in the maritime domain would be complex to secure if the Indian and Pacific oceans were divided in strategic perception. Thus, the term “Indo-Pacific” was born as a new regional strategic vision.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, in his address to the Indian Parliament in 2007, restored an ancient geographical view of Asia called “The Confluence of the Two Seas” (Chandra and Ghoshal 2018, 34), considering it a “dynamic coupling as seas of freedom and of prosperity” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2007) in Asia, set the target of linking the Pacific Ocean with the Indian Ocean to become the “Indo-Pacific” region, replacing the term of “Asia-Pacific”. The “Indo-Pacific” concept is supposed to be a geopolitical concept associated with countries inside and outside the geographical boundaries of the Asia-Pacific. Since 2010, this concept has become increasingly prevailing in strategic and geopolitical discourse and is employed by policymakers, experts, and scholars worldwide. Besides the geographical reference to the connection between the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean, the concept also has strategic and geopolitical significance, reflecting strategic changes, particularly in maritime security.

Regarding geographical space, the “Indo-Pacific” term is a connecting space between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, which combines these two oceans into a singular regional construct (Berkofsky and Miracola 2019, 13). This region mainly stretches from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of the US. Indo-Pacific is located along the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific Ocean, with the seas connecting these two oceans, including Northeast Asian, Southeast Asian, and South Asian countries, as well as many Middle East and African countries.

Regarding the roles, functions, connectivity, and interdependence of the two oceans, the Indo-Pacific has a diversity of ethnicities, religions, cultures, languages, and politics. This region has rich resources and important sea lanes, has the three largest economies in the world (the US, China, and Japan), is one of the most dynamic regions in terms of economy, and can support and promote each other between developed and developing economies. The Indo-Pacific has 9/10 busiest seaports in the world. About 60% of the world‟s maritime trade passes through this region, of which a third passes through the South China Sea (The US Department of Defense 2019). In addition, the sea route in the Indian Ocean is vital for transporting oil, gas, and goods worldwide, from the Middle East to Australia and East Asia. This is also a famously unstable sea with piracy and terrorism. Therefore, ensuring security for the lifeline of the world economy has received special attention from many countries.

Almost 90 percent of global trade and 2/3 of hydrocarbons have been transported across oceans, most concentrated in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The Indian Ocean, in particular, carries over half of all global container shipping capacity and accounts for around 70% of all transshipment hydrocarbons. The Indian Ocean is one of the busiest international maritime trade channels, accounting for 1/9 of global seaports and 1/5 of the world‟s import and export cargo (Zhu 2018, 4). Every year, more than 100,000 ships pass through the Indian Ocean, including 2/3 of the oil tankers, 1/3 of the large cargo ships, and 1/2 of the container ships in the world (Kumar and Hussain 2016, 151).

Strategically, the Indo-Pacific is viewed as a seamless structure connected by the strait of Malacca, the leading trade route connecting the two oceans. Two rationales explain the Indo-Pacific‟s strategic potential: Firstly, China‟s footprint throughout this region; secondly, the relative weakening of the US alliance system and its attempt to revive it (Das 2019).

With topographical tectonics, the Indo-Pacific is also an area that holds the world‟s most important sea lanes and is home to strategic “choke points” of the world - the Suez Canal, Bab-el-Mandeb and the Strait of Hormuz to the northwest, the Mozambique Channel to the southwest and the Strait of Malacca (the strategic connection point between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean), the Sunda Strait, and the Lombok Strait in the southeast and the Cape of Good Hope. In particular, the Strait of Hormuz accounts for 40% of global crude oil shipments. Between Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia, the Strait of Malacca holds half the world‟s merchant shipping tonnage (Kaplan 2010, 7). In the context of increasing tensions in the South China Sea, the strategic location of the Strait of Malacca has become the focus of attention of countries whose economies are heavily dependent on this nasopharyngeal shipping route. Currently, the amount of oil transported through this strait is three times higher than the Suez Canal and 15 times larger than the Panama Canal (Tan 2011, 93). It can be said that the Indo-Pacific region has the most critical position for international maritime trade and the intersection of the political and economic strategic interests of many powerful countries. This region plays an increasingly important role in the XXI century, becoming the focus and center of world power. However, the Indo-Pacific is witnessing geopolitical competition and competition of interests among major powers. The US, China, India, Japan, and Australia have all made strategic adjustments to increase their influence and protect their interests in this region.

The XXI century is considered “the century of seas and oceans” and is accompanied by fierce competition among world powers to gain strategic interests in the seas. In the past, nations primarily focused on competition for military objectives, geostrategic bases, and maritime traffic routes. However, in contemporary times, countries worldwide have shifted their focus towards competing for economic advantages and marine resources. The advancement of military capabilities and endeavours to vie for resources at sea increasingly indicate a trend toward leveraging maritime control to influence continental affairs. The “sea power” theory of US foremost thinker on naval warfare and maritime strategy - Alfred T. Mahan, has generated a premise for nations promoting sea power: “Control of the sea, by maritime commerce and naval supremacy, means predominant influence in the world; because however great the wealth product of the land, nothing facilitates the necessary exchanges as does the sea” (Mahan 1897, 124). Maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region has therefore become a “hot” focus in the maritime foreign policy agenda of powers. For the time being, the Indo-Pacific region is by and large peaceful and secure; however, it is confronted with some maritime security challenges:

Firstly, regarding maritime disputes, there are about 40 maritime disputes between countries in the region, which could be disputes over territorial sovereignty or sovereign rights over the waters. Many disputes, including those in the East China Sea, South China Sea, Indian Ocean, or Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, are viewed as potential flashpoints for a Sino-US war or even a Third World War (Echle et al. 2020, 126). While direct armed conflicts have yet to erupt in these areas, they serve as the underlying cause of the region‟s escalating security challenges. These conflicts stem primarily from the diverse security needs of numerous countries in the region. Moreover, given their strategic significance, these areas represent complex issues in Indo-Pacific maritime security, highlighting the intricate nature of the disputes.

Secondly, piracy and armed robbery have driven the Strait of Malacca, the South China Sea, and the Indian Ocean to the top of the list of the most dangerous waters. In 2018, the number of piracy and robbery cases in these areas was 8, 57, and 25, respectively, placing them second only to West Africa, which had 81 cases (International Maritime Organization, 2019, 2). While the number of piracy cases in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean decreased to 34 and 10, piracy cases in Malacca Strait increased to 45 in 2019 (International Maritime Organization 2020, 2). Another notable transnational maritime security issue in the Indo-Pacific is piracy off the coast of Somalia, which affects the waters of the Gulf of Aden, the Arabian Sea, and the Western Indian Ocean (Elleman et al. 2010, 210). In response to this threat, the United Nations Security Council has passed Resolution 1816, which states that cooperating countries may enter Somali territorial waters and use all necessary means to combat piracy and armed robbery (Klein 2011, 280).

Thirdly, alongside piracy, the Indo-Pacific region serves as a focal point for terrorist organizations such as Al-Qaeda and Al-Shabab. Following the 11 September terrorist attacks (commonly known as 9/11), countries including Singapore, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia have consistently coordinated their naval forces to combat terrorism in the Strait of Malacca, safeguarding oil tankers traversing the area. Additionally, new maritime security risks are emerging, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region, as terrorists exploit the Malay Archipelago as a sanctuary to identify vulnerable targets in the region and collaborate with extremists, Islamic insurgents, or members of organized crime networks. This fear has become much more real since the 2002 Bali bombings (Tan 2011, 91). Furthermore, terrorist organizations like Al-Qaeda, Abu Sayyaf, and Jemaah Islamiyah have extended maritime terrorism into Southeast Asia, affecting the broader region. The bombing of Super Ferry 14 in the Philippines in 2004 stands as the deadliest maritime terrorist attack globally to date, claiming the lives of 116 individuals (Safety4Sea 2019).

Lastly, drug trafficking and human trafficking are frequent transnational concerns in the Indo-Pacific. Many multinational organized criminal groups rely heavily on drug trafficking by water for a significant portion of their revenue. Drugs produced in Afghanistan, India, and Indonesia are transported by sea to other countries via illegal markets. The manufacture and transport of drugs are rising in the Indo-Pacific region, and criminal groups are exploiting the Malacca Strait as their primary distribution route to Southeast Asia countries (Zulkifli et al. 2020, 19). Moreover, the human trafficking issue remains unresolved as the coast guard, or the security department of port and ship facilities cannot predict the consequences.

Furthermore, one of the threats to maritime security in the Indo-Pacific region is arms trafficking. Most of the arms trade was carried by criminal organizations by sea in containers from southern Thailand to Aceh, Bangladesh, India, and Sri Lanka via the Malacca Strait and the Andaman Sea (Zulkifli et al. 2020, 19). The increase in arms trade is a significant contributor to the rise in maritime crime, particularly in Southeast Asia and the broader Indo-Pacific region. Consequently, territorial and maritime sovereignty disputes, coupled with the intricate linkages between transnational crime, piracy, and terrorism, have heightened the complexity of security threats in the marine domain. These developments strongly influence the adaptation of foreign strategies by several major powers, including China, India, and the United States.

THE STRATEGIC ADJUSTMENTS OF SOME MAJOR POWERFUL COUNTRIES FOR THE INDO-PACIFIC REGION

The Indo-Pacific region, with nearly half of the Earth‟s population, is at the center of the world‟s political and economic strategic interests. Currently, being rich in resources, many “throat” sea routes, and most dynamic economic and trade activities, this region plays an increasingly important role in the XXI century and beyond. However, the Indo-Pacific has been experiencing intense geopolitical competition, increasing pressure on trade and supply chains, and tensions in the technology, political, and security sectors. Great powers such as the US, China, India, Japan, and Australia have all made strategic adjustments to increase their influence and protect their interests in this region.

United States of America

Although not the first country to propose the Indo-Pacific concept, the US pioneered executing and implementing the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy. In recent years, the power has responded to global geopolitical changes by developing an Indo-Pacific strategy that seeks to rebalance the US to Asia as a counterweight to China‟s rise, developing alliances and partnerships to strengthen the Washington authority‟s interests over a large area stretching from the west coast of India to the west coast of the country. The US first coined the term “Indo-Pacific” through Secretary of State Hillary Clinton‟s official speech in Honolulu in October 2010. In 2017, following his inauguration, President Donald Trump intensified the term “Indo-Pacific” in official policy discourse (Turner and Parmar 2020, 229).

In early June 2019, the US Department of Defense officially announced the Indo-Pacific Strategy Report for the first time. This strategy aims to enhance the US‟s bilateral alliances and multilateral cooperation mechanisms across economic, security, and maritime domains, establishing a comprehensive network spanning South, Southeast, and Northeast Asia. Subsequently, in November 2019, the US Department of State released a Progress Report detailing the implementation of the Indo-Pacific strategy. These developments underscore the significance of US engagement in the Indo-Pacific region as a top priority in President Donald Trump‟s foreign policy agenda.

President Donald Trump chose the Indo-Pacific to underscore India‟s historical and contemporary significance in the region while affirming US interests and those of other countries. During a press conference in early April 2018, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Alex N. Wong elaborated on the concept, offering insights into how the Trump administration defines “freedom” and “openness”. According to Wong, “freedom” in the strategy primarily emphasizes international freedom, aiming for countries in the Indo-Pacific region to pursue their paths without coercion. At the national level, the US seeks to foster societies in the region that gradually embrace freedom, characterized by good governance, protection of fundamental rights, transparency, and anti-corruption measures. On the other hand, “openness” is primarily focused on expanding sea and air traffic. Maritime traffic is crucial to the region‟s vitality, as approximately 50% of international trade traverses the Indo-Pacific, mainly through the East Sea. Therefore, expanding sea and air routes in the Indo-Pacific is increasingly vital and significant on a global scale (Le 2018).

The US‟s “Vision for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific” was born for two primary reasons. Firstly, it stems from the internal factors of the US that are associated with the vital nature of national security and the role of the US in the world. As an area adjacent to many oceans, gateways, and throats connecting the US with the world, the Indo-Pacific has always been considered by the US to be a critical geostrategic area, directly affecting national security and the world leadership role of America. Implementing the FOIP strategy is a way for the US to protect national interests, ensure the freedom and security of maritime traffic, maintain the balance of forces, and promote diplomatic activities and society-culture exchanges in the area.

Second, stemming from the regional security situation, China‟s rise along with construction and militarization in the East Sea are seen as threatening the free flow of trade, threatening to narrow the sovereignty of countries, and reducing stability and security in the region. Not only that, but China‟s BRI is also challenging the US‟s leadership role in the Indo-Pacific region - where there is no multilateral mechanism on security, mainly based on bilateral agreements and arrangements, such as the US-Japan Security Treaty, the US-South Korea bilateral defense treaty (Pham and Vu 2020, 103-104).

The US‟s Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy is constructed upon three fundamental pillars: security, economy, and governance. The objectives of this strategy are multifaceted. Firstly, it aims to sustain long-term US leadership within the Indo-Pacific region and globally, particularly in light of China (and Russia) being explicitly identified by the US as America‟s primary strategic competitors in the National Security Strategy of 2017 and the National Defense Strategy of 2018. Secondly, the strategy promotes free, fair, and reciprocal trade. The US opposes trade deficits and unfair trade practices by other nations, instead demanding equal and responsible behaviour from its trading partners. Thirdly, it aims to uphold open sea and airspace within the region. Fourthly, it effectively addresses traditional and non-traditional security challenges, including North Korea‟s nuclear program. Lastly, the strategy strives to ensure adherence to the rule of law and the protection of individual rights (The US Department of Defense 2019). The US‟s Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy focuses on ensuring the country‟s interests, focusing on the “4P” formula in a clear order of priority: prosperity, peace, power through the deployment of American power, and finally, influence through American values and principles – Principles (Nguyen 2021a, 49).

US‟s Indo-Pacific Strategy is expected that the vital sea lanes of the Indo-Pacific will “create the foundation for the global trade and prosperity” (The US Department of Defense 2019). Therefore, the US strives to promote a Free and Open Indo-Pacific by promoting economic, governance, and security linkages. The core goal of the US‟s Indo-Pacific strategy is to build an alliance axis, Quadrilateral Security Dialogue1 (QUAD) (including the US, Japan, Australia, and India) to curb and prevent China‟s rise in the region, gain dominance, and control the entire region, thereby continuing to maintain the economic interests, political power, military and diplomatic power of the US (Pham and Vu 2020, 103). This is one of the main pillars that help to realize this connectivity strategy between the two oceans. The QUAD aims to foster the sharing of common interests, values, and perceptions of security threats among the four member countries. This collaboration aims to establish a balanced power dynamic that upholds a “rules-based” order in the Indo-Pacific region. On 12 March 2021, the QUAD officially convened online to reaffirm its primary maritime security mission. The overarching objective is to counteract China‟s growing regional and global influence (The White House 2021a).

Besides QUAD, on 15 September 2021, the US, UK, and Australia officially announced establishing a tripartite security partnership in the Indo-Pacific region (AUKUS). The first step can confirm that AUKUS is a new structure prone to “triangle” security in the Indian Ocean. The Pacific Ocean space aims to protect and maintain the shared interests of the parties in this region. A joint statement by US President Joe Biden, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison, and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson affirmed the partnership in AUKUS “guided by the enduring ideals and shared commitment to the international rules-based order” (The White House 2021b). This alliance aims to “help sustain peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region” (The White House 2021b).

[1] The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) was established in 2007 with four member countries: the US, Australia, Japan, and India. Its primary objective was to establish a trans-Pacific economic mechanism, potentially serving as the nucleus of the Asia-Pacific Economic Forum (APEC). After a 10-year hiatus, the QUAD group officially resumed the four-way dialogue in 2017, elevating it to a dialogue of foreign ministers. This resurgence occurred amidst heightened tensions between the US and China across various fronts, with Beijing's assertive behaviour posing security concerns for Japan, India, and Australia (Buchan and Rimland 2020, 3; Brunnstrom 2017).

Therefore, the US‟s efforts to promote strategic cooperation, enhance engagement across economic, political, and security domains, and forge partnerships and alliances with regional countries reflect its ambitions in the Indo-Pacific. The Free and Open strategy serves as an extension of the “America First” policy, gradually bolstering the role and preserving the influence of the US in the region.

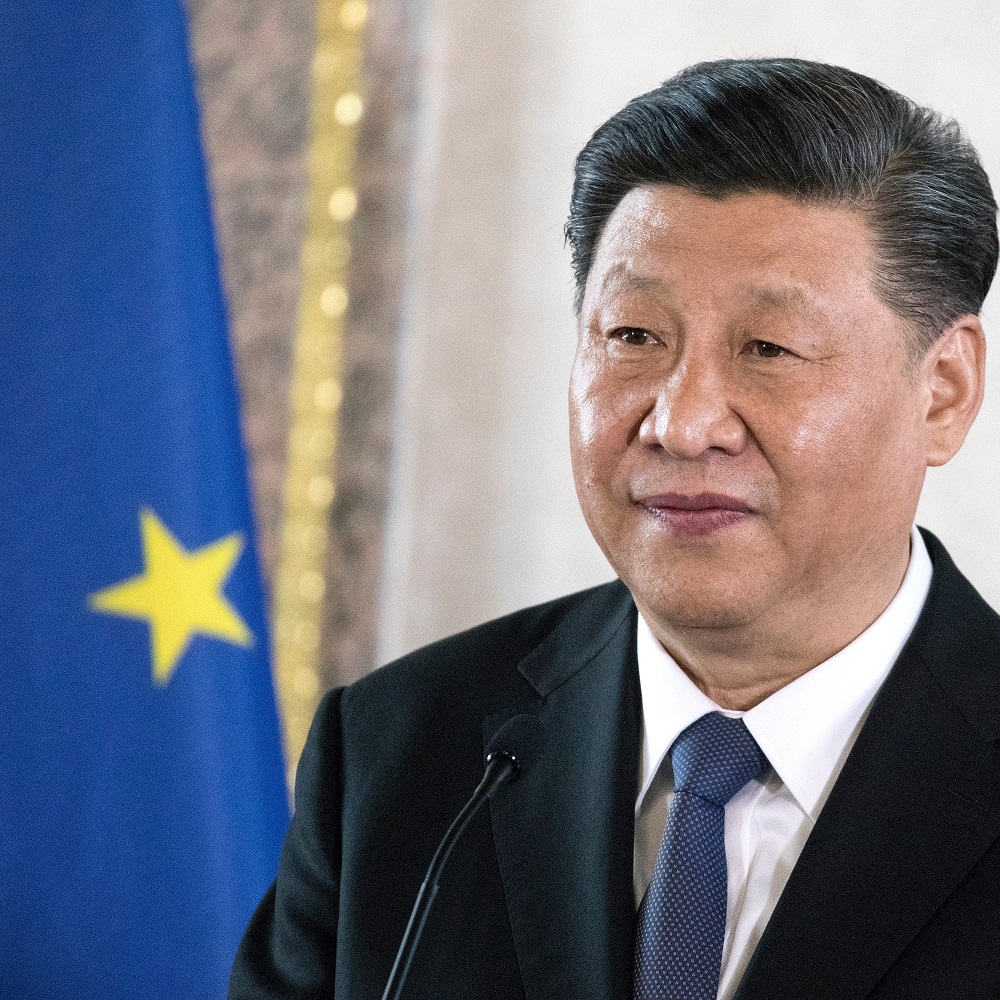

China

As a major power in Asia and globally, China inevitably focuses on strategically significant regions like the Indo-Pacific. Since the Cold War, particularly in the first two decades of the XXI century, China‟s ascendance has profoundly impacted global development, reshaping power distribution worldwide. This perspective is echoed by Robert D. Kaplan, a professor at the US Naval Academy: “China is currently changing the balance of power in the Eastern Hemisphere. On land and at sea, its influence extends from Central Asia to the Russian Far East and from the East Sea to the Indian Ocean” (Kaplan 2012, 200). China has stepped up its presence in the Indo-Pacific with the “String of Pearls” strategy and the “Belt and Road” Initiative (BRI).

“String of pearls” is a term coined by American analysts to describe China‟s network of shipping lanes extending from southern China to the Indian Ocean, traversing strategic points such as the Strait of Mandab, the Strait of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Strait of Lombok. It also encompasses other fundamental naval interests, including Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, the Maldives, and Somalia. Within this network, notable installations such as the military base on Hainan Island, the container shipping facility in Chittagong (Bangladesh), the deep-water port in Sittwe, the Kyaukpyu port, the Yangon port (Myanmar), the naval base in Gwadar (Pakistan), and the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka are referred to as the “jewels” or “pearls”. This chain of “pearls” extends from the coast of China, through the East Sea, the Strait of Malacca, across the Indian Ocean, and to the reefs of the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf (Kaplan 2012, 200). Each “jewel” within the “String of Pearls” represents China‟s geopolitical influence or military presence in key regions such as the Indo-Pacific, the East Sea, and other strategically significant seas. Through this strategy, China aims to extend its influence from Hainan in the East Sea through the world‟s busiest sea lanes towards the Persian Gulf. The primary objectives include restraining India, ensuring energy security, and asserting control over vital shipping lanes (Tran 2012, 77).

To implement the “String of Pearls” strategy, China has improved relations with most of India‟s neighbours, including Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. In that context, Myanmar is a place that China can use as a springboard for its ambitions to expand its sphere of influence into Southeast Asia and South Asia (Gupta 2013, 82). Myanmar has an important strategic position between two major Asian countries, China and India. Besides, Myanmar is a coastal country in the Indian Ocean, so for Chinese policymakers, Myanmar is increasingly of more strategic value to China. Myanmar is strategically important to India and a key player in China‟s ambitions to reach the Indian Ocean. Myanmar is the only neighbouring country that can give China access to the Indian Ocean from the east, namely the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea (Myo 2015, 26-27).

China’s moves in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea are the first steps to ensure China’s best interests in the Indian Ocean. China has also assisted Myanmar in developing naval bases at Sittwe, Hianggyi, Khaukphyu, Mergui, and Zadetkyi Kyun by building refuelling facilities and radar stations for Chinese submarines to operate on the Bay of Bengal (Singh 2007, 3). These facilities gather intelligence on Indian Navy activities and are forward bases for Chinese Navy operations in the Indian Ocean. With India‟s naval expansion efforts at a standstill, the Chinese Navy‟s growing presence in the region has had enormous strategic consequences for India because India‟s traditional geographical advantages are increasingly threatened by China‟s ability to penetrate deeper into Myanmar. According to US military experts, the “String of Pearls” is the basis for China to inspect and monitor all vital sea lanes in Asia and the world, curb India, Japan, and Korea, and gain the advantage of direct access to strategic locations in the Pacific.

“String of Pearls” strategy, China strengthens ties with regional countries through aid, trade, and defense agreements and launches new cooperation initiatives. In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This initiative consists of two main parts: (i) The Silk Road Economic Belt (also known as the Land Silk Road) is a roadway designed with three branches (from China to Central Asia and Russia to Europe, from China through Central Asia, West Asia to the Persian Gulf, the Mediterranean Sea, from China to Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Indian Ocean); (ii) Maritime Silk Road in the XXI century aims to build transport routes between major ports in different countries, including the development of an economic corridor across the Indian Ocean, connecting China with South Asia, the Middle East, Africa and the Mediterranean (Pham 2019, 31-32).

The objectives of this BRI are: first, to expand the strategic space and create a backyard area of China to control the Eurasian - African continent, creating a counterbalance to the US‟s Indo-Pacific strategy; second, dominate the Indian and Pacific Ocean regions, control related shipping lanes and regional seaport systems, dominate oil and gas supplies, establish military bases in these areas through which these roads pass; third, create a socio-economic environment for the expansion of China‟s “soft power”; fourth, build a security perimeter around China to prevent the US and its allies from entering the area that Beijing considers its “backyard”, supporting China to go out into the world; fifth, promote regional economic cooperation, rely on economic cooperation to promote political relations, create a catalyst to solve problems in relations between China and countries in the region, prevent the contraction of countries in the region that have disputes with China, including the issue of maritime and island disputes; sixth, through the “5 channels” (through policy, communication (on land, at sea), trade, currency and people) to access, penetrate and control the regional economy in order to promote economic development in the region to take control of international trade, the right to evaluate and the right to distribute international resources; seventh, solve the problem of excess production capacity, find a market for stagnant goods, find an investment market, effectively use China‟s huge foreign exchange reserves, find a market for the yuan, speeding up the process of internationalization of the renminbi; Eighth, access to energy resources, especially oil and gas; Ninth, take advantage of the surrounding environment to create conditions for more equal development among regions in the country, especially the border areas, western China (Dinh 2021, 7-8). China‟s BRI prioritizes the maritime sector when it proposes the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road” to connect seaports, one of the two main connections between China and Europe (Kuo and Kommenda 2018). It can be said that the BRI aims at strategic goals in terms of politics, security, economy, territorial sovereignty, and building a new framework of rules of the game in the region and the world, in which China plays a leading role (Tran 2017, 100).

In addition, to counterbalance the Indo-Pacific strategy of the US and the QUAD, China has strengthened its relations with Russia and Iran by strengthening the Sino-Russian alliance in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and admitted Iran to this organization on 17 September 2021. China, Russia, and Iran have formed a “new maritime power triangle” and are preparing to launch a joint maritime exercise in the Persian Gulf. Previously, in December 2019, these three countries also conducted a joint maritime exercise in the Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Oman in the context of tensions between Washington and Tehran showing signs of escalation.

India

As a continental power occupying a strategic position in the heart of the Indian Ocean, India has become a prominent player in the Indo-Pacific region and one of the countries deploying manoeuvres to adjust foreign strategy. India‟s “Look East” policy (implemented since 1992) has extended India‟s foreign strategy to Southeast and East Asian countries. Over the years, India‟s regional involvement has shifted from economic ties to security cooperation. Prime Minister Narendra Modi‟s “Act East” policy (implemented since 2014) underpins India‟s approach to the Indo-Pacific region, in which this foreign policy will strengthen India‟s participation through strategic partnerships. In addition, the country has its vision for the Indo-Pacific region. India wants to promote peace and stability through an equal approach at sea and air, freedom of navigation, combating maritime crime, protecting the marine environment, and developing a green economy (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India 2018). In 2015, in the Report “Ensuring Maritime Security: India‟s Maritime Security Strategy”, India clearly stated that its strategic vision shifted from the Euro-Atlantic to the Indo-Pacific, associated with the “Act East” policy. In his speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue (June 2016), Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi laid out India‟s vision for the Indo-Pacific region, emphasizing India‟s participation in organizations, taking ASEAN as the center of the region, such as the East Asia Summit (EAS), the ASEAN Defense Ministers Meeting Plus (ADMM+).

Indian Prime Minister N. Modi first announced the Indo-Pacific Initiative during his speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue held on 1 June 2018 in Singapore. Prime Minister N. Modi affirmed, “The Indo-Pacific is a natural region (...) India does not see the Indo-Pacific Region as a strategy or as a club of limited members” (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India 2018). On 4 November 2019, Prime Minister N. Modi once again mentioned this idea at the 14th East Asia Summit (EAS), held in Bangkok (Thailand), which “propose a cooperative effort to translate principles for the Indo-Pacific into measures to secure the shared maritime environment” (Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India 2019). This proposal also transforms India‟s conception of the Indo-Pacific region into practical and enforceable measures in the maritime domain.

Regarding the policy, India has demonstrated its determination to implement the Indo-Pacific Initiative through the establishment of a Directorate-General for the Indo-Pacific under the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) since April 2019, based on merging international organizations, such as ASEAN, the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) and the QUAD including the US, Japan, Australia, and India. In September 2020, India continued to establish the Directorate for Oceania in the MEA to promote India‟s administrative and diplomatic fields, stretching from the Western Pacific Ocean to the Andaman Sea.

India‟s Indo-Pacific Initiative consists of 7 pillars, including 1) Marine security, 2) Marine ecosystems, 3) Marine resources, 4) Capacity building and resource sharing, 5) Disaster risk reduction and management, 6) Technology and trade cooperation, and 7) Connectivity and shipping, which can be grouped into six groups: 1) Maritime security; 2) Marine ecosystems and marine resources; 3) Building maritime enforcement capacity and information sharing; 4) Manage and reduce disaster risks; 5) Science and technology cooperation; 6) Trade connection and sea transportation (Nguyen 2021). India‟s approach to this strategy is inclusive and transcends traditional security issues or geopolitical challenges. India also wants to promote cooperation in environmental issues related to the sea and ocean sectors. Through the Indo-Pacific Initiative, India wishes to lead, chair, and coordinate in cooperation inside and outside the region, especially with small and medium-sized countries.

Compared to the US‟s Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy, India expands the geographical reach of the region under the Indo-Pacific Initiative, whereby the Indo-Pacific covers the African coast to the west of the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea, including neighbouring countries in the Gulf, islands in the Arabian Sea and the African region. By asserting “both geographical poles” of the Indo-Pacific Initiative, India emphasizes the balance between the two groups of policies, “Act East” and “Act West”, forming an integral part of the country‟s strategy in the Indo-Pacific region.

For India, strengthening security cooperation with the US, forging a special strategic partnership with Japan, and maintaining the relationship with Australia are strategic focuses in shaping economic and security architecture in the region based on the “diamond quadrilateral” alliance. At the same time, to connect with the open Indo-Pacific space, India also strengthened ties with Asian, European, and African countries.

CONCLUSION

Due to the Indo-Pacific region‟s current structural makeup, the major regional powers have gradually turned it into a strategic area of power competition. Countries interested in the region actively participate in the Indo-Pacific regional architecture and seek ways to strengthen their positions to act as a counterweight in regional international affairs. Today, the Indo-Pacific is seen as a crucial element in the changes in global geopolitics and the focal point of numerous power struggles. In this region, besides the US, two Asian powers play a major role in regional security, China and India, because both countries seem to be putting all their efforts into improving regional security, greater competition than other areas due to their position. India is prepared and actively involved in a motivated strategy against China in the Indo-Pacific, in contrast to other regions where it has historically been more passive and weaker. India is moving toward the US in this competition but maintaining a neutral stance. Additionally, it is working to increase influence and fortify multilateral ties to close the power gap with China.

With regard to China‟s growing influence in the region and its security implications for India and other regional countries, there exists a wide pessimism, particularly in Western analyses. It is quite pertinent to point out here that the India - China relationship is nicely balanced between the elements of cooperation and conflict, like that of the US-China relationship. Especially there is enough space in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond to accommodate both rising China and India. They can coexist and grow peacefully. However, the trends and issues will ostensibly continue to unfold in the region with greater worrying security concerns. In the coming years, maritime security within the Indo-Pacific region will be a key factor in the development of many countries. It, however, remains a major concern in the area because of the growing non-traditional security threats, in addition to maritime boundary disputes. Particularly, events in the SCS will continue to attract much of the regional and international attention. These could engulf the regional and international stakeholder‟s capability to maintain peace, security, and stability within the region in a sustained and effective manner.

Most importantly, countries in the Indo-Pacific region share many of these common concerns. Invigorating greater cooperation and coherence in their strategy could help address the problems collectively. Moreover, establishing an Indo-Pacific Regional Security Architecture will be very handy in addressing common security concerns and threats.

As a result, as the Indo-Pacific area is being shaped, the competition between the major powers is also becoming more complex and severe, significantly impacting the other nations in the region. In short, during the first two decades of the XXI century, the Indo-Pacific region has witnessed constant competition among numerous world powers. The region‟s strategic, economic, and commercial significance has positioned it at the heart of global contention, reshaping the character of international politics. The Indo-Pacific has become the focal point of international conflicts and power dynamics, heralding a significant new geopolitical landscape in the XXI century. It can be asserted that the power competition among these nations will shape the interaction patterns among Indo-Pacific countries in the ensuing years of this century.

Funding: This research is funded by the Ministry of Education and Training (Vietnam) under grant number B2023-DHH-05.

REFERENCES

1. Berkofsky, A. & Miracola, S. 2019. “Geopolitics by Other Means: The Indo-Pacific Reality”.Milan: Ledizioni LediPublishing.

2. Brunnstrom, D. 2017. US seeks meeting soon to revive Asia-Pacific „QUAD‟ security forum, available at: https://cdn.thefiscaltimes.com/latestnews/2017/10/27/US-seeks-meeting-soon-revive-Asia-Pacific-Quad-security-forum (6 April 2024)

3. Buchan, P.G. & Rimland, B. 2020. “Defining the Diamond: The Past, Present, and Future of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue”. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), available at: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/200312_BuchanRimland_QuadReport_v2%5B6%5D.pdf (6 April 2024)

4. Chandra, S. & Ghoshal, B. 2018. “The Indo-Pacific Axis: Peace and Prosperity or Conflict”.New York: Routledge.

5. Cohen, S. B. 2014. “Geopolitics: The Geography of International Relations”, 3rd edition. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

6. Das, U. 2019. “What is the Indo-Pacific?”. The Diplomat, available at: https://thediplomat.com/2019/07/what-is-the-indo-pacific/ (25 May 2021).

7. Deudney, D. H. 2013. “Geopolitics”. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/geopolitics (20 May 2022).

8. Dinh, C. T. 2021. “Chiến lược của Trung Quốc đối với khu vực Ấn Độ Dương - Thái Bình Dương và hàm ý chính sách cho Việt Nam” [China's Strategy towards the Indo-Pacific Region and Policy Implications for Vietnam], Vietnam Review of Northeast Asian Studies, 3 (241):3-12.

9. Echle, C., Gaens, B., Sarmah, M.& Rueppel, P. 2020. “Responding to the Geopolitics of Connectivity: Asian and European Perspectives”, Bonn: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung.

10. Elleman, B. A., Forbes, A. & Rosenberg, D.2010. “Piracy and Maritime Crime: Historical and Modern Case Studies”. Newport: Naval War College Press. 11. Flint, C. 2006. “Introduction to Geopolitics”. New York: Routledge.

11. Fouberg, E. H., Murphy, A. B. & De Blij, H. J. 2012. “Human Geography: People, Place, and Culture”,10th edition. New Jersey: Wiley.

13. Gupta, R. 2013. “China, Myanmar and India: A Strategic Perspective”.Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, 8 (1): 80-92.

https://doi.org/10.1080/09700160701355485

https://doi.org/10.1177/186810341503400202

14. International Maritime Organization2019. “Reports on Acts of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships: Annual Report - 2018”. London.

15. International Maritime Organization2020. “Reports on Acts of Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships: Annual Report - 2019. London.

16. Kaplan, R. D. 2010. “Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power”. New York: Random House.

17. Kaplan, R. D. 2012.“The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us about Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate”. New York: Random House.

18. Khurana, G. S. 2007. “Security of Sea Lines: Prospects for India-Japan Cooperation”. Strategic Analysis, 31(1):139-153.

19. Klein, N. 2011. “Maritime Security and the Law of the Sea”. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

20. Kumar, S., Dwivedi, D.& Hussain, M. S. 2016. “India‟s Defence Diplomacy in 21st Century - Problem & Prospects”. New Delhi: GB Books.

21. Kuo, L.& Kommenda, N. 2018. “What is China‟s Belt and Road Initiative?”, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/ng-interactive/2018/jul/30/what-china-belt-road-initiative-silk-road-explainer (17 May 2021).

22. Lacoste, Y. 2012. “Geography, Geopolitics, and Geographical Reasoning”. Hérodote, 146-147(3):14-44.

23. Le, H. H. 2018. “Chiến lược Ấn Độ Dương - Thái Bình Dương Mở và Tự do của Mỹ: Một góc nhìn từ Việt Nam”[America‟s Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy: A Perspective from Vietnam], available at: http://nghiencuuquocte.org/2018/08/20/an-do-duong-thai-binh-duong-viet-nam/ (10June 2022).

24. Mahan, A. T.1897. “The Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future”. Boston: Little, Brown & Company.

25. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India2018. “Prime Minister‟s Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue”, available at: https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/29943/prime+ministers+keynote+address+at+shangri+la+dialogue+june+01+2018(23 May 2021).

26. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India 2019. “Prime Minister‟s Speech at the East Asia Summit”, available at: https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements.htm?dtl/32171/Prime_Ministers_Speech_at_the_East_Asia_Summit_04_November_2019(23 May 2021).

27. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 2007. “Confluence of the Two Seas”, available at: https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html (20 July 2021).

28. Morgenthau, H. J. 1948. “Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace”. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

29. Myoe, M. A. 2015. “Myanmar‟s China Policy since 2011: Determinants and Directions”. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 34(2):21-54.

30. Nguyen, H. H. 2021. “Đông Nam Á trong chiến lược Ấn Độ Dương - Thái Bình Dương của Hoa Kỳ”[Southeast Asia in the US Indo-Pacific Strategy]. Hanoi: Social Sciences Publishing House.

31. Nguyen, T. X. S. 2021. “Sáng kiến Ấn Độ Dương - Thái Bình Dương của Ấn Độ: Từ chính sách đến hành động” [India's Indo-Pacific Initiative: From Policy to Action], available at: https://www.tapchicongsan.org.vn/web/guest/the-gioi-van-de-su-kien/-/2018/824192/sang-kien-an-do-duong---thai-binh-duong-cua-an-do--tu-chinh-sach-den-hanh-dong.aspx(30 December 2021).

32. Pham, S. T. 2019. “Sáng kiến Vành đai - Con đường (BRI): Lựa chọn nào của Đông Nam Á?” [Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): Which is Southeast Asia‟s Choice?]. Hanoi: World Publishing House.

33. Pham, T. T. B. & Vu, N. Q. 2020. ““Chiến lược Ấn Độ Dương - Thái Bình Dương tự do và rộng mở” của Hoa Kỳ: Vai trò và cách thức triển khai” [The US's "Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy": Role and Implementation Method". Journal of Communism, Vietnam, 938:102-06.

34. Safety4Sea Website 2019. “Superferry14: The World‟s Deadliest Terrorist Attack at Sea”, available at: https://safety4sea.com/cm-superferry14-the-worlds-deadliest-terrorist-attack-at-sea/ (06 March 2022).

35. Singh, Y. 2007. “India‟s Myanmar Policy: A Dilemma Between Realism and Idealism”.IPCS Special Report, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, New Delhi, 37:1-5.

36. Tan, A. T. H. 2011. “Security Strategies in the Asia-Pacific: The US‟ “Second Front” in Southeast Asia”. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

37. The US Department of Defense 2019. “Indo-Pacific Strategy Report: Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region”, available at: https://media.defense.gov/2019/Jul/01/2002152311/-1/-1/1/DEPARTMENT-OF-DEFENSE-INDO-PACIFIC-STRATEGY-REPORT-2019.PDF(20 May 2021).

38. The White House 2021. “Joint Leaders Statement on AUKUS”, available at:https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/15/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus/(15 September 2022).

39. The White House 2021. “Quad Leaders‟ Joint Statement: „The Spirit of the Quad‟”, available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/03/12/quad-leaders-joint-statement-the-spirit-of-the-quad/ (12 March 2022).

40. Tran, N. T. 2012. “Chiến lược “Chuỗi ngọc trai” và mục tiêu trở thành cường quốc biển của Trung Quốc trong thế kỷ XXI” [The "String of Pearls" Strategy and China's Goal of Becoming a Maritime Power in the 21st Century]. Chinese Studies Review, Vietnam, 1(125): 64-80.

41. Tran, V. T. 2017. “Vành đai, Con đường": Hướng tới Giấc mộng Trung Hoa" [The Belt and Road: Towards the "Chinese Dream"]. Journal of Communism, Vietnam, 895: 100-05.

42. Tuathail, G., Dalby, S. & Routledge, P. 1998. “The Geopolitics Reader”. New York: Routledge.

43. Turner, O. & Parmar, I. 2020. “The US in the Indo-Pacific: Obama‟s legacy and the Trump transition”. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

44. Zhu, C. 2018. “India‟s Ocean: Can China and India Coexist?”. Singapore: Social Sciences Academic Press and Springer.

45. Zulkifli, N. I., Raja, R. I., Rahman, Abdul, A. A. & Yasid, Mohd, A. F. 2020. “Maritime Cooperation in the Straits of Malacca (2016-2020): Challenges and Recommendations for a New Framework”. Asian Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences, 2(2):10-32.