Diplomacy

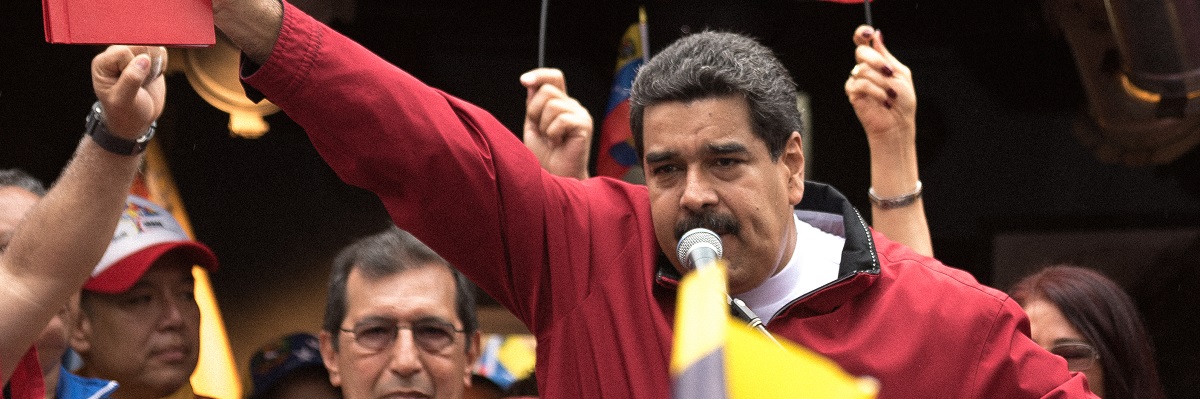

Venezuela: why Maduro is ramping up his attack on free speech

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

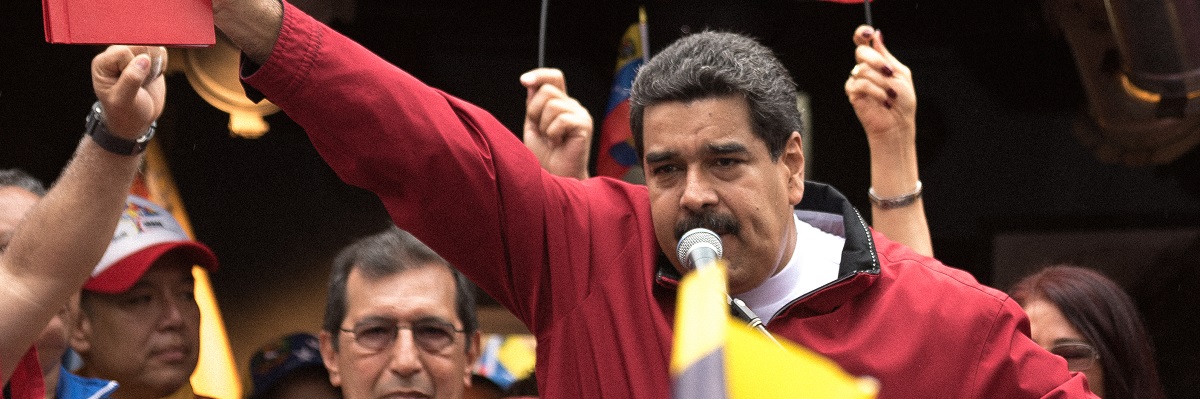

Diplomacy

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Apr.16,2024

May.10, 2024

Oscar Alejandro Pérez, a popular Venezuelan YouTuber who uploads travel videos, was arrested on terrorism charges on Sunday, March 31. Pérez was detained, and subsequently held for 32 hours, over a video he uploaded in 2023. In the video, he points to the Credicard Tower, a building in Caracas that hosts the servers that facilitate the country’s financial transactions, and jokingly adds: “If a bomb were to be thrown at that building, the whole national banking system would collapse.” He was accused of urging people to blow up the building, something Pérez denies. His arrest is the latest evidence of President Nicolás Maduro’s growing crackdown on human rights and civil liberties as the country prepares for presidential elections in July. Maduro’s predecessor, Hugo Chávez, was a hugely popular president. While in office, he led a social and political movement called the “Bolivarian Revolution”, which aimed to address social, economic and political inequalities through a series of progressive reforms funded by Venezuela’s vast oil wealth. Then, in 2013, Chávez died and Maduro (who was then vice president) came to power after narrowly winning a special election. Initially, Maduro enjoyed the sympathy and support of many Venezuelans loyal to Chávez and his socialist ideals. But since taking office Maduro has presided over a series of economic crises. Hyperinflation, shortages of basic goods, and a deep recession have all made him increasingly unpopular. And Venezuela’s economy has contracted by about 70% under Maduro’s leadership.

The last time Venezuelans went to the polls was in 2018. The contest was so rigged that many neighbouring countries branded the election illegitimate. Two of the most popular opposition candidates were disqualified or barred from running, and Maduro won the contest amid claims of vote rigging and other irregularities. Many Venezuelans have grown disillusioned with Maduro and have taken to the streets to vent their anger. But widespread discontent and protests have only fed more insecurity, criminality, poverty and social unrest. Now lacking support from within the Chavista political movement and the Venezuelan military, Maduro has turned to criminal groups to promote a state where illegal armed groups act at the service of the government. Maduro has consolidated power by using state institutions to silence critics, while at the same time engaging in human rights abuses and profiting from corruption. He has been accused of committing crimes against humanity, including torture, kidnapping and extrajudicial killings. And according to Amnesty International, between 240 and 310 people remain arbitrarily detained on political grounds. Unsurprisingly, around 7.7 million Venezuelans have fled repression and economic hardship at home. Roughly 3 million of those displaced have started a new life in Colombia, 1.5 million of them have migrated to Peru, while others have made their way north to the US. The Venezuelan migrant crisis has become the largest in the world, with the number of displaced people exceeding that seen in Ukraine and Syria.

Venezuelans will head to the polls on July 28. The arrest of Pérez is part of a wider strategy aimed at silencing dissent and strengthening the regime’s hold over its people as Maduro seeks re-election. On February 9, a prominent lawyer and military expert Rocío San Miguel was arrested in Caracas before several members of her family disappeared. San Miguel is known for her work exposing corruption in the Venezuelan army. She appeared at a hearing four days later accused of “treason, conspiracy and terrorism” for her purported role in an alleged plot to assassinate Maduro. Her arrest set off a wave of criticism both inside and outside Venezuela, including from the UN Human Rights Council. Its office in Caracas was subsequently ordered to stop operations on the grounds that it promoted opposition to the country and staff were told to leave the country within 72 hours. It is unclear whether San Miguel remains in jail. In March, Ronald Ojeda, a 32-year-old former lieutenant in Venezuela’s military, was found dead in Chile ten days after he had gone missing. He had protested against the Maduro government on social media wearing a T-shirt with “freedom” written on the collar and prison bars drawn on the map of Venezuela. His body was found in a suitcase beneath a metre of concrete. Chilean prosecutors later announced that his abduction and killing was the work of El Tren de Aragua, one of Venezuela’s most powerful criminal organisations.

The crackdown on civic society poses a dilemma for the Biden administration. In October 2023, Maduro secured a partial lifting of US economic sanctions (which have been in place since 2019) in return for a commitment to holding “free and fair” presidential elections, in addition to political reforms and the release of political prisoners. But that deal is quickly unwinding. In January, the leader of the opposition and a clear favourite in the polls, María Corina Machada was banned from holding office for 15 years. The Biden administration has since reimposed some sanctions and has threatened new ones on Venezuela’s vital oil sector if political reforms are not made. Venezuela has become a deeply corrupt, authoritarian and criminal state that shuts down dissent, forces millions of its own people to flee, and kills or abducts whoever threatens the regime. Its occasional displays of reason are motivated purely by economic gain. In many ways, Maduro’s political repression reflects his growing fear that his regime’s days are numbered, driving him to desperate measures to force a different fate. Once a dictator takes hold, it becomes very difficult to dislodge them.

First published in :

Nicolas is a Professor of Management at Essex Business School (EBS), and Co-director of the Centre for Latin American Studies (CLACS) at the University of Essex, one of the longest-established centres of its kind. An economist by background, his research interests revolve around organized crime in Latin America, the regeneration of the city of Medellin in Colombia, and issues of social justice in Colombia and Latin America. He leads an innovative module entitled 'Business and Social Justice in Latin America' at the University of Essex. Nicolas has published in academic journals, online and in professional publications, as well as book chapters. He's recently contributed a book chapter on Colombia's economy after three decades of economic reforms, and a series investigating the legacy of COVID-19 in Latin America.

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!