Diplomacy

Romania’s election aftershock

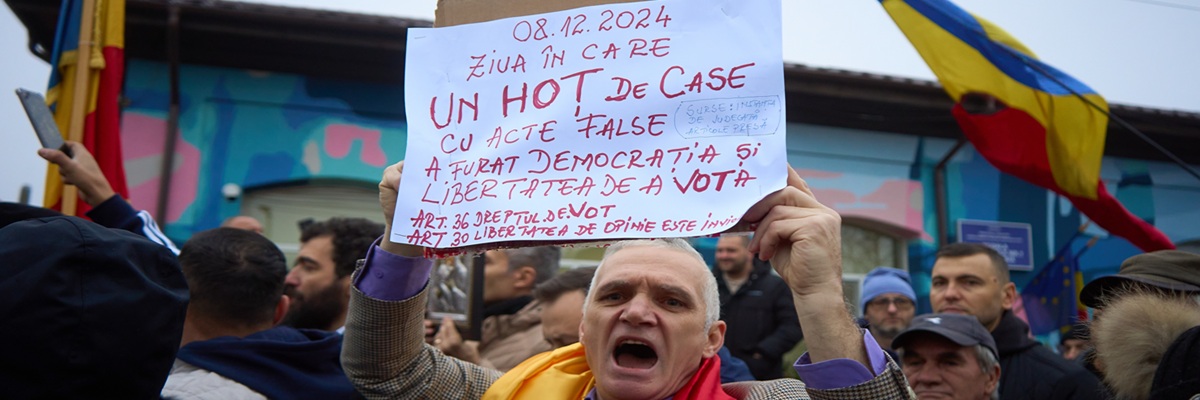

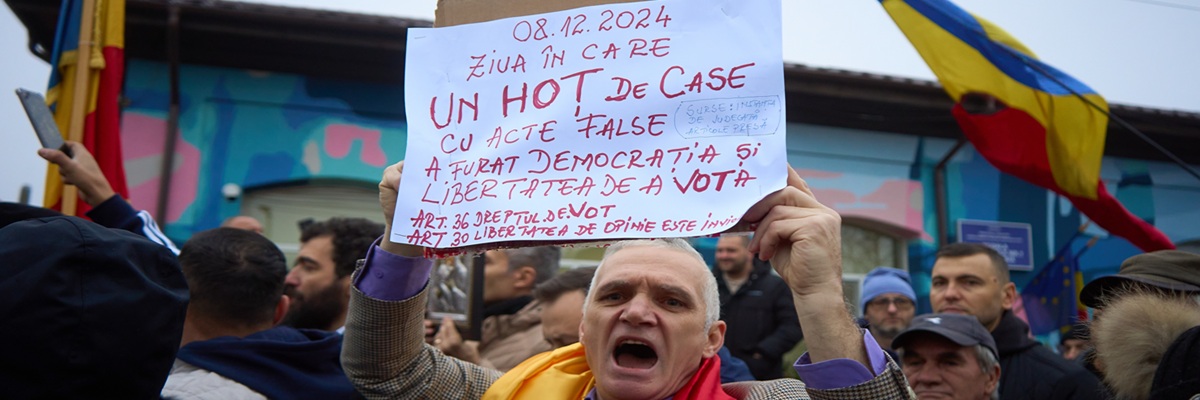

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Diplomacy

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Dec.09,2024

Dec.30, 2024

Social media manipulation, rural discontent and mainstream complacency: Romania’s cancelled elections offer a stark warning for Europe’s democracies

E lections are rarely straightforward, especially in high-stakes environments — and particularly in Romania. The EU member state at the Black Sea, which shares the longest border with Ukraine and, until now, has been a staunch US ally and trusted NATO member, now faces profound political uncertainty following the abrupt cancellation of its presidential elections last Friday.

The elections were halted after intelligence services revealed interference in the electoral process by a ‘state actor’, widely presumed to be Russia, aimed at favouring an unexpected far-right candidate. The Constitutional Court intervened, ordering a complete restart of the electoral process. Proceeding with the second round under these circumstances would have effectively turned it into a de facto hidden referendum on Romania’s pro-Western orientation.

However, the crisis is far from resolved. The electoral turmoil has left Romania’s democratic mainstream fragmented and facing difficult choices. Stabilising the economy, reducing the fallout from the political crisis and forming a functional parliamentary majority are critical tasks.

The Romanian case offers crucial takeaways for other European nations, particularly regarding the disruptive role of social media platforms like TikTok in democratic elections. Curbing Russia’s hybrid warfare capabilities, which exploit these platforms to stoke public anxieties and deepen political divisions, requires swift and coordinated action at the European level.

A far-right surge nobody saw coming

Romania’s presidential and parliamentary elections were supposed to be held in succession between 24 November and 8 December, with the parliamentary elections sandwiched between the two rounds of the presidential election. The sudden rise of the independent candidate Călin Georgescu, until recently a fringe figure, as a serious contender in the first round of the presidential election triggered a far-right surge. The parliamentary election results that followed one week later revealed the fragility of the democratic mainstream against the radical right, which nobody could have predicted mere weeks ago.

Georgescu’s unexpected victory in the first presidential round dealt a heavy blow to Romania’s traditional parties, the Social Democrats (PSD) and the centre-right National Liberals (PNL), which have formed the governing coalition since 2021. Not only were their candidates – Prime Minister Marcel Ciolacu (PSD) and Senate Chairman Nicolae Ciucă (PNL) – both surpassed by Georgescu. But the parties themselves each lost almost 10 per cent compared to previous elections.

The Social Democrats recorded their worst performance in history, securing 22 per cent of the vote and 123 mandates (down from 157). Although they remain Romania’s largest political force, their ability to form a stable majority is now in question. Meanwhile, the National Liberals lost half their seats, securing only 72 mandates. The other centre-right party, Save Romania Union (USR), fared no better, dropping from 90 to 59 mandates, in spite of their candidate, Elena Lasconi, entering into the presidential runoff with Georgescu.

This is in stark contrast to the gains made by the radical right. The Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR) surged into second place with 18 per cent of the vote, while two other smaller far-right parties – SOS Romania and the Party of Young People (POT) – crossed the five per cent threshold for the first time. Together, radical right-wing factions now control almost 35 per cent of the new legislature.

Who is the far-right candidate who has upended Romania’s politics? A 62-year-old self-proclaimed expert on sustainable development, Călin Georgescu has ties to the ultra-religious, ultra-nationalist movement that also propelled AUR into parliament in 2020. His relationship with AUR, however, was short-lived, as some of Georgescu’s controversial statements proved too extreme even for this party.

Dubbed ‘Kremlin Georgescu’ by some because of his Putin-friendly stance, he is no longer tethered to a single party — a factor that many believe has been crucial to his success in a country where trust in political parties is historically low. His blunt position on party politics is summed up in a short sentence: ‘Political parties are bankrupt’, he concluded after the parliamentary elections of 1 December.

His statement echoes another rant from April this year when he emphatically declared that ‘Political parties are nags for the golden chariot of the Romanian people. There will be no more political parties in this country. None!’ When questioned about this, Georgescu retorted that he had merely quoted from a Romanian philosopher, Petre Țuțea, a former member of the Iron Guard, a fascist, ultra-nationalist organisation during Romania’s inter-war period. Țuțea’s exact quote, however, would send shivers down anyone’s spine: ‘Political parties are horses for the golden chariot of Romanian history; when they become nags, the Romanian people send them to the slaughterhouse.’

It’s all about the support for Ukraine

Georgescu didn’t just reject party politics, he also questioned the core pillars of Romania’s foreign policy — its membership of NATO and the EU, and the US security umbrella. In Georgescu’s view, NATO is ineffective as a defensive alliance. He recently described the Deveselu Aegis Ashore anti-missile defence system, which Romania has been hosting since 2015, as a ‘disgrace to diplomacy’. While other presidential candidates reaffirmed Romania’s commitment to Ukraine, Georgescu campaigned on the promise of pursuing ‘peace’ through rapprochement with Russia, a move that aligns with his praise of ‘Russian wisdom’ in foreign policy.

His position resonated with voters increasingly anxious about the war’s economic and security implications. Romania, which shares a long border with Ukraine, has felt the effects of the conflict through rising energy prices, an influx of refugees and trade disruptions. Public sentiment has shifted in recent months, influenced in part by debates in US politics about ending the war in Ukraine. Georgescu’s populist rhetoric, bolstered by the re-election of Donald Trump, helped him capitalise on these war-related anxieties and positioned him as a challenger to the status quo.

Georgescu’s surprising rise reflects deep societal divisions in Romania and growing disenchantment with the political and economic establishment. His support is concentrated among voters in rural and economically disadvantaged regions, areas that have long felt neglected by post-communist reforms. A 2021 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) study described these regions as ‘rural and old industrial areas with significant socio-economic challenges’, where many residents experienced the transition to democracy and capitalism as a period of frustration, humiliation and injustice.

Georgescu’s platform, ‘Food, Water, Energy’, resonated with voters in these areas. The programme proposes policies at odds with EU norms, including nationalisation and preferential taxation for local businesses. These ideas appealed to small farmers and business owners struggling with rising production costs and competition from cheap Ukrainian grain imports. EU environmental regulations, perceived as burdensome, further fuelled discontent. Protests by Romanian farmers earlier this year, blocking border crossings with Ukraine and Moldova, highlighted these grievances.

His rhetoric also struck a chord with Romanians working abroad, many of whom feel abandoned by the state. For decades, urban centres have benefited disproportionately from EU funding and foreign investment, leaving the peripheries to fend for themselves. Georgescu positioned himself as the champion of the forgotten majority, offering a voice to those who felt excluded from Romania’s post-communist success story.

A TikTok made Manchurian candidate

TikTok proved to be the ‘secret weapon’ that catapulted Georgescu into the political spotlight. Just weeks before the elections, he was virtually unknown to the public, but his discreet TikTok campaign rapidly expanded his reach within days. Declassified documents from Romania’s intelligence services reveal that Georgescu’s TikTok network spanned 25 000 accounts and allegedly received substantial support from a ‘state actor’. Notably, around 800 of these accounts, initially created as early as 2016, remained largely dormant until two weeks before the elections. This highlights the alarming vulnerability of modern politics to manipulation via social media platforms.

TikTok’s popularity in Romania – 47 per cent of the population has an account – has made the platform a powerful tool. By contrast, only 36 per cent of people in France and less than 27 per cent in Germany have an account on TikTok. Among voters aged 18-24, who predominantly use this platform, Georgescu secured 30 per cent of the vote, far outpacing his support among older demographics. This is the age group that, according to a recent FES Youth Study, declares the highest fear of violence and war (56 per cent), sees corruption as the main problem for Romania (72 per cent) and agrees with the statement that it would be good for Romania to have a strong leader who doesn’t care much about the parliament and elections (41 per cent).

This is, however, only a small part of the picture. While social media played a role in Georgescu’s success, allowing him to rise from obscurity, the rest has to do with a combination of factors that culminated in a cascade of failures and bad decisions of the mainstream parties.

The inability of Romania’s mainstream political parties to acknowledge and address the fears, anxieties, and grievances of the electorate alienated many voters. Amid rising concerns about an impending economic downturn and the deteriorating situation in Ukraine, the political class appeared detached from reality. Although the grand coalition remained in government, the Social Democrats and National Liberals devoted much of the electoral campaign to petty controversies and fruitless disputes, failing to engage with issues that mattered to voters.

This relentless squabbling overshadowed any opportunity to highlight the government’s notable achievements, which were far from insignificant. These included massive progress on infrastructure projects on a scale unprecedented in the past two decades, Romania’s inclusion in the US Visa Waiver Program and a landmark breakthrough toward full Schengen accession.

Adding to this, the lacklustre presidential candidates fielded by the mainstream parties compounded voter frustration and drove many to seek alternatives. The Social Democrats’ overconfidence resulted in sloppy campaign planning and a narrow focus on a single strategy that hinged on their candidate, Marcel Ciolacu, facing far-right AUR candidate George Simion in the presidential runoff. This strategy was decisively upended by Georgescu’s unexpected surge.

Moreover, the PSD’s ‘accommodationist stance’ toward AUR – rooted in the party’s preference for transactional, give-and-take politics – contributed to the normalisation of far-right narratives centred on ethnic nationalism and Christian conservatism. This approach not only weakened the democratic mainstream but also provided fertile ground for the radical right to gain legitimacy and momentum.

As Romania grapples with its largest budget deficit in years and faces mounting political uncertainty, the ability of democratic forces to regroup and form a stable majority will be critical in the weeks to come. So far, all parties from the democratic mainstream, Social Democrats included, have signalled that they understand how important it is to form a stable majority. Failure to do so risks further empowering extremist forces and destabilising the nation’s pro-European trajectory.

First published in :

Cristian Chiscop works as Programme Coordinator at the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung’s Romania Office.

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!