NATO and the Russian Federation in Ukraine: The ongoing struggle

by Javier Fernando Luchetti

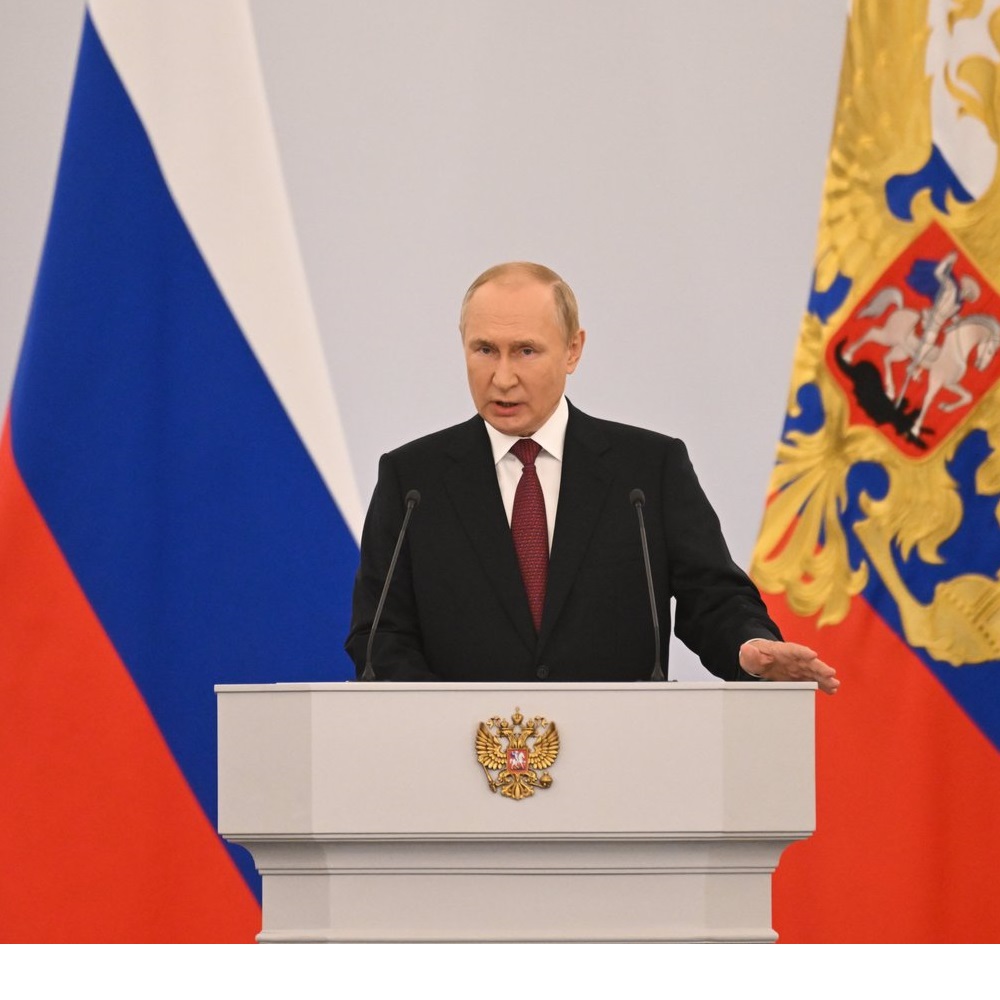

한국어로 읽기 Leer en español In Deutsch lesen Gap اقرأ بالعربية Lire en français Читать на русском Introduction For some international analysts, the invasion by Vladimir Putin, President of the Russian Federation, into the Republic of Ukraine, led by Volodymyr Zelensky, on February 24, 2022, was a surprise. This offensive was meant to conquer Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, and Kharkiv, the second-largest city in the country. However, the war that was expected to be quick and low-cost in terms of human lives, with an aura of liberation from the "neo-Nazi government" and the "Ukrainian oligarchy," turned into a much slower and bloodier conflict than the Kremlin anticipated. It is important to clarify that in 2014, the Russian Federation annexed the Crimean Peninsula, which was part of the territory of Ukraine. Shortly after, pro-Russian rebels from the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, supported by Moscow, began a popular uprising, leading to a civil war against Ukrainian troops. In 2019, when pro-Western President Volodymyr Zelensky came to power, clashes between both sides intensified. In February, before the invasion, Putin signed decrees recognizing the republics of Donetsk and Luhansk in eastern Ukraine as independent states, accusing the United States (U.S.) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) of expanding eastward into Europe, pushing Ukraine’s membership in NATO, and threatening Russia's sovereignty and territorial integrity. During the first week of the war, the Ukrainian president ordered a general military mobilization to defend Ukrainian territory from the Russian advance, while both the U.S. and its European Union (EU) allies announced political and economic sanctions (energy, transport, finance) against the Russian Federation and the expulsion of Russian banks from the SWIFT system, the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication, which includes over 11,000 financial institutions from over 200 countries. This system, based in Brussels, Belgium, was created to facilitate fast and secure cross-border payments and relies on confidentiality, validity, and accessibility of information from participating members. Western multinationals sold their assets in Russia and canceled any partnerships with Russian firms. These measures took Putin by surprise, although thanks to his alliance with China for the sale of gas and oil, he was able to navigate the blockade. Price hikes hurt Russian workers, who saw their income decrease due to rising prices for essential goods. As stalled negotiations continued between the Russians and Ukrainians, Russian troops halted due to Ukrainian resistance, which received weapons and supplies from NATO. This work provides a brief description and analysis of the factors that led to the Russian Federation’s invasion of the Republic of Ukraine and its economic and political consequences for both countries, as well as the role of the U.S. and NATO in the conflict. This invasion is simply a continuation of the longstanding conflict between both countries, especially since the first decade of the 21st century due to territorial and geopolitical issues involving NATO, the Russian Federation, and the Republic of Ukraine. In this regard, NATO expanded eastward after the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), despite Putin’s warnings. 1. A crisis that began before 2022 In March 2014, a referendum against the opinion of Kyiv was held in Crimea and the autonomous city of Sevastopol, in which pro-Russian inhabitants, who were the majority, decided to join the Russian Federation. This referendum was not accepted by Ukraine, the U.S., and the EU, thus, Moscow incorporated Crimea into its territory, claiming that the peninsula had always been part of Russia. Meanwhile, in April, pro-Russian paramilitary groups took the regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, which are adjacent to Russia, with supplies and weapons from Moscow. By May, referendums in Donetsk and Luhansk declared the regions as independent republics, although they did not want to join the Russian Federation. The Minsk I Agreement, signed in 2014 between Russia and Ukraine under the auspices of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), established a roadmap to end the civil conflict and normalize the status of both regions. It aimed for a permanent ceasefire, decentralization of power, the release of hostages, border monitoring with Russia, elections, improved health conditions, and the withdrawal of foreign fighters. The Minsk II agreement, signed in 2015, called for an immediate ceasefire, the withdrawal of heavy weapons from both sides, pension payments to residents, the establishment of a sanitary zone, elections, prisoner exchanges, and the granting of autonomy to the region, allowing Ukraine to recover the border areas with Russia. Both agreements failed, and fighting resumed. Putin consistently claimed that Ukraine had no intention of implementing the agreements and had only signed them due to military losses, while for the U.S. and its allies, Putin always intended to recognize the independence of both regions, betting on the failure of the negotiations. 2. The Russian Federation and the Republic of Ukraine: The war between both countries Putin had warned months earlier that Western powers, led by the United States, should negotiate with him over the expansion of NATO eastward, which was affecting Russia’s security. Putin demanded that Ukraine not be forced to join NATO, arguing that such a move would not provide any security guarantees for Russia. However, the invasion was not unexpected, as weeks before there had been satellite images showing the deployment of Russian troops and armored vehicles: "Russia had also announced, albeit inconsistently and unclearly, that it would adopt ‘technical-military’ measures against Ukraine if its demands for security guarantees and neutrality regarding the Atlantic Alliance were not accepted" (Sanahuja, 2022, 42). Ukraine’s incorporation into NATO would mean that biological, nuclear, and chemical weapons could be stationed there, something the Russians deemed unjustified since the Warsaw Pact had disappeared in 1991 with the dissolution of the USSR. What the Russian Federation sought, as the world’s second-largest military power, was to prevent missiles from pointing at its territory from Ukraine due to NATO’s expansion and U.S. militaristic intentions. The Russian Federation, as one of the key international actors, even as a state strategically involved across multiple continents, felt cornered and overwhelmed in its strategic interests. The Russians sought NATO guarantees to prevent further expansion and desired security at the old geopolitical style for their borders: "On other economic and strategic issues, the Russian state continues to control its vital areas. Corporations controlling hydrocarbons, aerospace, and infrastructure, among others, are state-owned" (Zamora, 2022). On the other hand, Russian nationalism, which considered Ukraine and Russia to be sister nations, has served as a justification for the invasion. Early in the century, Putin was closer to Western positions, but after seeing that his concerns about NATO’s expansion were ignored, he turned to Russian nationalism, seeking to create a ‘hinterland’ in the old Tsarist style, denying Ukraine’s status as an independent state and instead treating it as a historical product allied with Russia. Another reason for Putin to invade Ukraine was to defend the two “people's republics” in the Donbas region: Donetsk and Luhansk. The Russian Federation recognized both regions as "sovereign states" because they had never been granted autonomy. From Putin’s perspective, the invasion was based on the United Nations Charter, which stated that a country under a "genocide" by its government should receive help, as was happening in the two “sovereign states.” According to his view, the measures taken by the Russian Federation were related to Ukraine’s political indecision in controlling the paramilitary militias that were attacking the two independent republics. Due to the failure of the Minsk agreements, Russia was forced to intervene. Following this reasoning, before the Russian intervention, the U.S. and its allies had begun providing significant amounts of modern weapons, not only to rearm the Ukrainian military forces but also to give them the ability to invade Donbas. The Ukrainian army, along with intelligence services trained by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), constituted a risk for the pro-Russian population in Donbas, so despite Western warnings, the Russian Federation was compelled to intervene. To summarize, in the first phase, Moscow's objectives were to overthrow the “neo-Nazi” government of Kyiv (although this objective was sidelined later due to Ukrainian resistance and Western sanctions), prevent Ukraine from joining NATO to avoid missiles close to its borders, defend the pro-Russian population of Donbas, secure recognition of Russian sovereignty over Crimea, and finally declare the independence of the republics of Luhansk and Donetsk, or, as happened later, hold referendums to annex these regions to the Russian Federation. However, the United Nations General Assembly thought differently from the Russian leader and approved in March the resolution 2022, A/RES/ES-11/1, for humanitarian aid in Ukraine, condemning “in the strongest terms the aggression committed by the Russian Federation against Ukraine” (article 2), demanding “that the Russian Federation immediately cease the use of force against Ukraine” (article 3), and calling for “the immediate, complete, and unconditional withdrawal of all Russian military forces from the territory of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders” (article 4). At the same time, while reinforcing the military front, the Russian Federation economically cut gas supplies to Western European countries. What the war demonstrated was the adaptability of the Ukrainian military to fight under unfavorable conditions, using elastic attacks in different places with help from terrain knowledge, spies, and satellite images and drones provided by the U.S. and its allies. The U.S. aid approved by the government of Joseph Robinette Biden Jr. until 2023 reached 40 billion dollars through the Lend-Lease Act for the Defense of Democracy in Ukraine. (Sanahuja, 2022). On the contrary, on the Russian side, the underestimation of the resistance of Ukrainian armed forces, the "Special Military Operation," was compounded by the underestimation of Ukrainian national sentiment, combined with planning problems, tactical issues, supply and logistics challenges, and the low morale of soldiers who did not want to fight against Ukrainians, despite the Kremlin’s calls to battle the "oligarch and neo-Nazi cliques" running Kyiv’s government. Furthermore, ignoring the warnings from the West and Kyiv, Putin announced the annexation of the territories of Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia, after the results of the referendums showed over 95% support for annexation to the Russian Federation. In response to the annexation, Ukrainian President Zelensky officially requested Ukraine's membership in NATO. This confirmed the definitive cutoff of gas supplies to Europe, causing concern in industries across various countries, especially in small and medium-sized enterprises. 3. The United States, NATO, and China Currently, China and India are the leading buyers of Russian gas, even more so than all of Europe, with discounts granted by the Russians. This demonstrates that the world is no longer unipolar, but multipolar, with the decline of Europe and the economic rise of the People's Republic of China (PRC) and India. While the U.S. leads militarily and is economically stronger than Russia, it is less powerful than the PRC. Therefore, attacking a Chinese ally with nuclear weapons is weakening the PRC, which does not possess many nuclear weapons itself. The U.S. helped the disintegration of the USSR, and now it also seeks the disintegration of the Russian Federation, or at least a regime change, distancing Putin from power and ensuring that the new government is more friendly with the West. This is despite the initial intention of Putin during his first term to join NATO, a request that was denied, and the Russian help (accepting the installation of U.S. bases in Central Asian countries) that the U.S. received when it invaded Afghanistan, when both countries had the same enemies (the Taliban and Al-Qaeda). Although the Russian Federation has not been able to freely use its dollar reserves, as part of them were held in Western countries, it has also benefited from the rise in gas and oil prices, which it continued to export, particularly to the PRC, which has not joined the sanctions. These price hikes not only disrupted the global economy, generating inflation in NATO countries but also increased the prices of minerals and energy, harming capitalist countries and, paradoxically, benefiting the Russians as they sell these commodities. The Russian economy has resisted more than expected, and the ruble, which depreciated at the beginning of the conflict, has recovered. Those who suffered the consequences of the sanctions were the Europeans who import gas and oil. For the U.S. and its allies, the next enemy to defeat is China, as, according to them, global problems require global solutions. Additionally, China has been criticized for not sanctioning and condemning the Russian Federation. The Russian Federation is considered a threat to peace by NATO because it seeks, through coercion and annexation, to establish a sphere of influence and direct control with conventional and cyber means, destabilizing Eastern and Southern European countries. If there was any semblance of autonomy by European countries towards the U.S., the crisis has shattered those efforts. Before the crisis, the U.S. complained that Europeans were not doing enough to maintain the alliance, specifically by increasing the percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) dedicated to defense. The Ukrainian situation has placed them under the U.S. wing, and that autonomy has vanished for the time being. With the election of Donald Trump as president, the situation in Ukraine enters a new phase. Although the Ukrainian president has stated that technical teams have been formed to address the issue of the war with the Russians, there is still no set date for a meeting. Trump also pointed out that Putin is destroying Russia after years of war, generating inflation and economic problems due to the lack of an agreement to end the conflict, although he did not provide specifics on a potential meeting with the Russian president. Trump has encountered a war whose resolution is clearly more complicated than he initially believed. However, from the Russian side, President Putin stated, “we listen to your statements about the need to do everything possible to avoid a Third World War. Of course, we welcome that spirit and congratulate the elected president of the U.S. on his inauguration,” which could be interpreted as an approach to the new administration (Infobae, 2025). The U.S. president, during his presidential campaign had announced that he would end the war in 24 hours, but then the deadline was extended to 100 days. However, now he is seeking a meeting with his Russian counterpart in the coming months, which has proven that the solution to the Russo-Ukrainian war is more complicated than it seemed. Trump has also threatened new sanctions on the Russian Federation if it does not sit at the negotiation table. He has also mentioned that he expects Chinese help to pressure Moscow to seek an end to the conflict. In summary, the U.S. president is more interested in solving internal issues like Latin American migration at the Mexican border than in addressing a war that has lasted almost three years. Final Comments The Republic of Ukraine has been used by Western powers to curb the anti-unipolar stance of the Russian Federation. To maintain Western predominance, the U.S. and allied countries have launched a struggle against the Russians, but through Ukraine, cooperating militarily, politically, and economically. The security policy developed by the U.S. in recent years has shown, on one hand, the growing military power with the maintenance of bases worldwide, from which they can attack or at least influence various countries to defend their interests. On the other hand, the use of this policy has led to the decline of the U.S. economy in the face of competition with the PRC, which has not only increased its GDP but also its productivity, foreign investments, and technological development. In other words, today, Russia is the main opponent, an ally of China, and later, it will be China. The U.S. foreign policy, which sought Ukraine’s membership in NATO, has led Putin to intervene militarily in an invasion in which he believed he would be received as a liberator but encountered fierce nationalist resistance, despite calling the Ukrainian leaders "neo-Nazis." The Russian response to NATO’s eastward expansion is related to security concerns. But they also point to the injustice committed by Western countries. According to the Russians, while they were sanctioned for the invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. was not sanctioned when it invaded Iraq, nor was NATO when it intervened in Libya. The U.S. considered the invasion as an attack on the international order and on American supremacy in the European continent, which is why they are intervening in Ukraine — to attack an invading power that seeks to recover its geopolitical role at both the regional and global levels, as it had during the USSR era. The outcome of the war remains uncertain, as the Ukrainians have invaded and occupied a large part of the Russian region of Kursk, where they have taken towns and prisoners to use as bargaining chips in future negotiations with Russia, while the destruction of infrastructure and the death toll continue to rise. References 1. -Infobae. (2022). Putin vuelve a jugar la carta nuclear y llama a falsos referendos para anexionar cuatro provincias de Ucrania. Buenos Aires. 21 de septiembre. https://www.infobae.com/america/mundo/2022/09/21/putin-vuelve-a-jugar-la-carta-nuclear-y-llama-a-falsos-referendos-para-anexionar-cuatro-provincias-de-ucrania/2. -Infobae. (2022). Vladimir Putin anunció la anexión de las regiones ucranianas de Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson y Zaporizhzhia. Buenos Aires. 30 de septiembre. https://www.infobae.com/america/mundo/2022/09/30/vladimir-putin-anuncio-la-anexion-de-las-regiones-ucranianas-donetsk-luhansk-kherson-y-zaporizhzhia/3. -Infobae. (2025). Trump dijo que Vladimir Putin está “destruyendo a Rusia” por no buscar un acuerdo de paz con Ucrania. Buenos Aires, 21 de enero. https://www.infobae.com/estados-unidos/2025/01/21/trump-dijo-que-vladimir-putin-esta-destruyendo-a-rusia-por-no-buscar-un-acuerdo-de-paz-con-ucrania/4. -Luchetti, J. (2022). El papel de la Federación Rusa y Estados Unidos en la guerra ruso-ucraniana. 2° Congreso Regional de Relaciones Internacionales “(Re) Pensar las Relaciones Internacionales en un mundo en transformación”. Tandil. 28, 29 y 30 de Septiembre.5. -Luchetti, J. (2022). Rusia y la OTAN en Ucrania: la lucha por la supremacía en un país del viejo continente. XV Congreso Nacional y VIII Internacional sobre Democracia “¿Hacia un nuevo escenario internacional? Redistribución del poder, territorios y ciberespacio en disputa en un mundo inestable”. En, C. Pinillos (comp.). Memorias del XV Congreso Nacional y VIII Internacional sobre Democracia. Rosario. Universidad Nacional del Rosario, Facultad de Ciencia Política y Relaciones Internacionales, pp. 1098-1127. https://rephip.unr.edu.ar/handle/2133/260936. -Naciones Unidas. (2022). Asamblea General. Resolución A/RES/ES-11/1. Agresión contra Ucrania. New York. https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n22/293/40/pdf/n2229340.pdf7. -Sanahuja, J. (2022). Guerras del interregno: la invasión rusa de Ucrania y el cambio de época europeo y global. Anuario CEIPAZ 2021-2022 Cambio de época y coyuntura crítica en la sociedad global. Madrid. Centro de Educación e Investigación para la paz, pp. 41-71. https://ceipaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/3.JoseAntonioSanahuja.pdf8. -Zamora, A. (2022). La multipolaridad contra el Imperialismo y la izquierda extraviada. Buenos Aires. Abril. https://observatoriocrisis.com/2022/04/23/la-multipolaridad-contra-el-imperialismo-y-al-izquierda-extraviada/