The Geopolitics of the War in Ukraine. (Is Geopolitics Still Relevant?)

by Krzysztof Śliwiński

한국어로 읽기Leer en españolIn Deutsch lesen

Gap

اقرأ بالعربيةLire en françaisЧитать на русском

*This is an abbreviated version of the same paper published by the author at: Śliwiński K. (2023). Is Geopolitics Still Relevant? Halford Mackinder and the War in Ukraine. Studia Europejskie – Studies in European Affairs, 4/2023, 7-25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33067/SE.4.2023.1

Abstract

This paper starts with an assumption that Geopolitics, understood as one of the great schools of International Relations, is not only still relevant but, indeed, should be one of the essential items in the toolkit of any student or policymaker who peruses the challenging and ever eluding realm of international security.

It draws chiefly on the Heartland theory of Halford Mackinder to explain the dynamics of contemporary European Security in general and the ongoing war in Ukraine in particular.

The analysis leads the author to a pair of conclusions: firstly, that the conflict in Ukraine is unlikely to end anytime soon and, perhaps more importantly, that the outcome of the war will only be one of many steps leading to the emergence of the new, possibly a multipolar, international system and consequently, and more obviously, a new security system in Europe, which will be strongly influenced by Germany rather than by the United States as before.

Keywords: Geopolitics, Heartland, Europe, Security, Ukraine

Introduction

In the wake of the outburst of the war in Ukraine, the members of the European Union agreed on an extensive package of sanctions against various Russian entities and individuals connected to Vladimir Putin, the president of Russia. Until the attack against Ukraine, the EU had been "muddling through" with numerous countries pursuing their national interests, shaping their individual foreign and security policies, notably vis-à-vis Russia. The attack reinvigorated calls from E.U. bureaucrats for more unity and an actual common defense. EU's chief diplomat Joseph Borrel, during an extraordinary plenary session of the European Parliament on March 1, 2022, urged the European Parliament’s MPs to "think about the instruments of coercion, retaliation, and counterattack in the face of reckless adversaries. […] This is a moment in which geopolitical Europe is being born", he stressed (Brzozowski, 2022).

Heartland theory – Geopolitics 101

As an analytical tool, geopolitics has been used since the 19th century. Its reputation was tarnished as a consequence of the policies of the Third Reich before and during WWII. Yet, it is considered a worthy approach that allows explanations that specifically look at the nexus between states' foreign and security policies and their geographical location in a historical context. Geopolitics is one of the grand theories of international relations (Sloan, 2017). Fundamentally, rather than treating states as separate, alienated geographical organisms, geopolitics allows us to look at a broader picture, including regions or even the whole globe, thus making it possible to account for interactions between many states functioning in particular systems defined by geographical criteria.

Today's war in Ukraine occurs in a vital region for the European continent – Central and Eastern Europe. One of the founders of Geopolitics, a scientific discipline – Halford Mackinder (British geographer, Oxford professor, founder and director of the London School of Economics) proposed an enduring model in his seminal publication at the beginning of the 20th century - The Geographical Pivot of History.

Drawing on the general term used by geographers – 'continental' Mackinder posits that the regions of Arctic and Continental drainage measure nearly half of Asia and a quarter of Europe and, therefore, form a grand 'continuous patch in the north and the center of the continent' (Mackinder, 1919). It is the famous 'Heartland', which, according to his inventor, is the key geographical area for anyone pursuing their dominant position in Euroasia. "[…] whoever rules the Heartland will rule the World Island, and whoever rules the World Island will rule the world" (Kapo, 2021). Notably, the key to controlling the Heartland area lies in Central and Eastern Europe, as it is an area that borders the Heartland to the West.

Twenty-First century geopolitics (Dugin vs Mearsheimer)

The most influential thinker and writer in Kremlin recently has arguably been Aleksandr Gel'evich Dugin. Accordingly, his 600-hundred pages book, Foundations of Geopolitics 2, published in 1997, has allegedly had an enormous influence on the Russian military, police, and statist foreign policy elites (Dunlop, 1997). In his book, Dugin, drawing on the founder of geopolitics, Karl Haushofer, posits that Russia is uniquely positioned to dominate the Eurasian landmass and that, more importantly, 'Erasianism' will ultimately hold an upper hand in an ongoing conflict with the representatives of 'Atlantism' (the U.S. and the U.K.). Crucially, Dugin does not focus primarily on military means as a way of achieving Russian dominance over Eurasia; instead, he advocates a relatively sophisticated program of subversion, destabilization, and disinformation spearheaded by the Russian special services, supported by a tough, hard-headed use of Russia's gas, oil, and natural resource riches to pressure and bully other countries into bending to Russia's will (Dunlop, 1997).

The Moscow-Berlin Axis

According to Dugin, the postulated New Empire (Eurasian) has a robust geopolitical foothold: Central Europe. "Central Europe is a natural geopolitical entity, united strategically, culturally and partly politically. Ethnically, this space includes the peoples of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, Germany, Prussia and part of the Polish and Western Ukrainian territories. Germany has traditionally been a consolidating force in Central Europe, uniting this geopolitical conglomerate under its control" (Dugin, 1997). Consequently, while the impulse of the creation of the New Empire needs to come from Moscow, Germany needs to be the centre of its western part. Furthermore "only Russia and the Russians will be able to provide Europe with strategic and political independence and resource autarchy. Therefore, the European Empire should be formed around Berlin, which is on a straight and vital axis with Moscow." (Dugin, 1997, 127).

Regarding the role of Anglo-Saxons in Central and Eastern Europe, Dugin offers a very straightforward analysis: "The creation of the Berlin-Moscow axis as the western supporting structure of the Eurasian Empire presupposes several serious steps towards the countries of Eastern Europe lying between Russia and Germany. The traditional Atlanticist policy in this region was based on Mackinder's thesis about the need to create a "cordon sanitaire" here, which would serve as a conflict buffer zone preventing the possibility of a Russian-German alliance, which is vitally dangerous for the entire Atlanticist bloc. To this end, England and France strove to destabilize the Eastern European peoples in every possible way, to instil in them the idea of the need for "independence" and liberation from German and Russian influences". It follows logically that "Ukraine as an independent state with certain territorial ambitions, represents an enormous danger for all of Eurasia and, without resolving the Ukrainian problem, it is, in general, senseless to speak about continental politics" (Dugin, 1997). "[T]he independent existence of Ukraine (especially within its present borders) can make sense only as a 'sanitary cordon'. Importantly, as this can inform us to an extent about the future settlement of the conflict: "The absolute imperative of Russian geopolitics on the Black Sea coast is the total and unlimited control of Moscow along its entire length from Ukrainian to Abkhazian territories".

The Tragedy of Great Power Politics

In the preface to the update of his seminal book "The Tragedy of Great Power Politics" (2013 edition), John Mearsheimer acknowledges that his analysis had to be updated with regards to the so-called "peaceful rise" of the People's Republic of China as a significant challenger to the role and position of United States in the international system. Consequently, he envisaged that the process would produce a highly sensitive, if not prone to local conflicts environment (Mearsheimer, 2013, 10). Following the logic of power balancing, he claimed that firstly, China had to build formidable military forces and, secondly, dominate Asia similarly to how the United States dominated Western Hemisphere. Correspondingly, China would strive to become a regional hegemon to maximise its survival prospect. This would make China's neighbours feel insecure and prompt counterbalancing by, as one might surmise, strengthening the existing bilateral and multilateral alliances and building new ones (AUKUS being a perfect example). Logically speaking, therefore, if you follow Mearsheimer's argumentation, Russia and India, Japan and Australia, and the Philippines and Indonesia should build a solid coalition to counter the ascent of China. Such developments would be in the interests of the United States, and Washington would naturally play a crucial role under such circumstances. Notably, the rise of China was not likely to be peaceful and produce "big trouble" for international trade as well as peace and security.

This was approximately what the Trump administration had in mind when preparing the national security strategy in 2017. The Strategy mentions Russia 25 times, frequently in connection with China, as major challengers to the U.S.: "China and Russia challenge American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity. They are determined to make economies less free and fair, grow their militaries, and control information and data to repress their societies and expand their influence" (National Security of the United States of America, 2017). Yet, after even a short analysis of the document, one identifies the difference between the two in terms of how the U.S. perceives the challenge that each represents. Regarding Russia, Washington concludes that Kremilin's main aim is to: "seek to restore its great power status and establish spheres of influence near its borders". China seems to be more ambitious in the eyes of the Capitol. As evidenced by such statements as: "Every year, competitors such as China steal U.S. intellectual property valued at hundreds of billions of dollars", "China seeks to displace the United States in the Indo-Pacific region, expand the reaches of its state-driven economic model, and reorder the region in its favour. China's infrastructure investments and trade strategies reinforce its geopolitical aspirations. Its efforts to build and militarize outposts in the South China Sea endanger the free trade flow, threaten other nations' sovereignty, and undermine regional stability."(National Security of the United States of America, 2017).

Given this perception, it is no wonder that under Trump, Washington embarked on a new mission that questioned the processes of globalization for the first time in many decades. Under Trump, the U.S.A. introduced numerous economic sanctions against China, which sparked a revolution called 'decoupling'. Johnson and Gramer, writing for foreignpolicy.com in 2020, questioned this policy: "The threat of a great decoupling is a potentially historical break, an interruption perhaps only comparable to the sudden sundering of the first massive wave of globalization in 1914, when deeply intertwined economies such as the Great Britain and Germany, and later the United States, threw themselves into a barrage of self-destruction and economic nationalism that didn't stop for 30 years. This time, though, decoupling is driven not by war but peacetime populist urges, exacerbated by a global coronavirus pandemic that has shaken decades of faith in the wisdom of international supply chains and the virtues of a global economy." (Johnson, Gramer, 2020).

With the comfort of looking at hindsight, we should conclude that perhaps luckily for the Far East and international political economy, Mearsheimer was wrong, at least for the time being. Firstly, no military conflicts exist in the Far East or the Pacific. The most potentially dangerous issue remains one of the cross-straight relations, i.e. P.R.C. vs Taiwan (Chinese Taipei). Whether Xi Jinping will risk another diplomatic backlash by an open invasion remains to be seen. The jury is out, and one might claim that with the world being focused on the war in Ukraine, China could get away with an invasion of Taiwan. Then, on the other hand, perhaps there is no need for the P.R.C. to unite all territories of China in the imminent future forcefully.

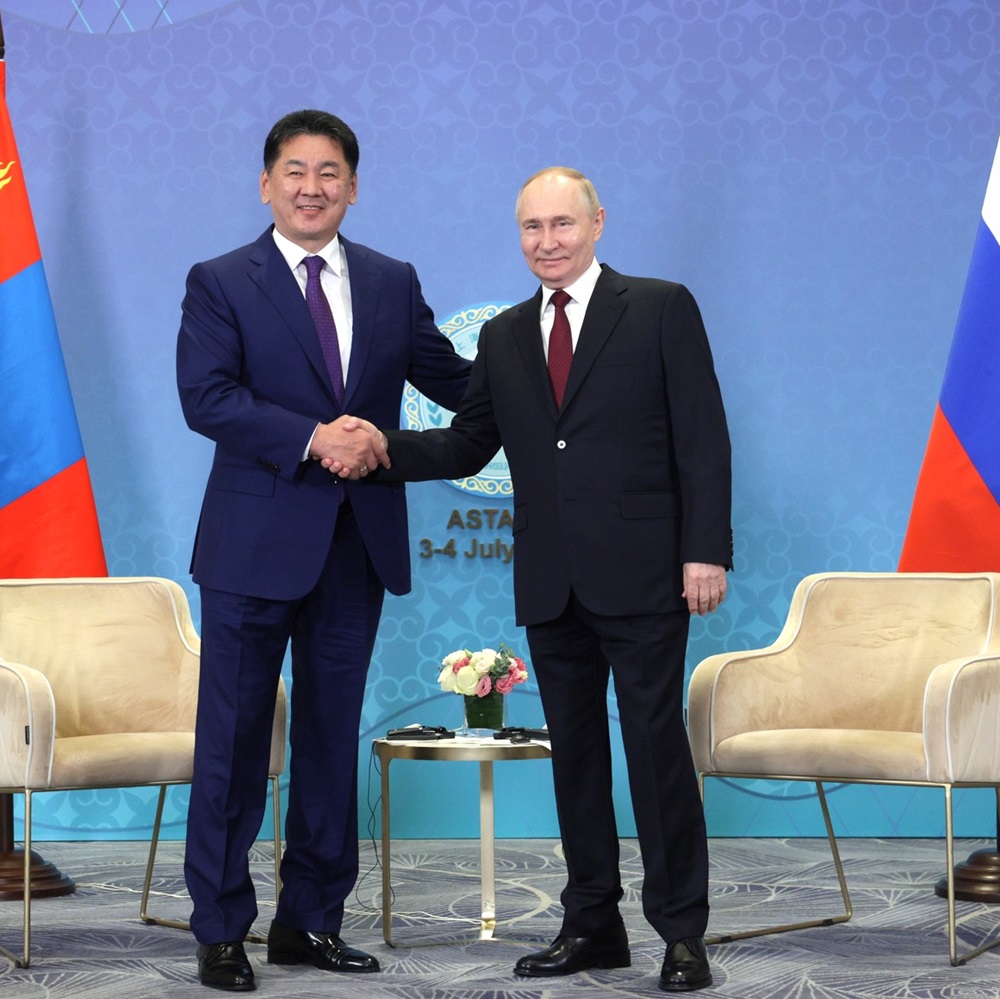

At the same time, as it appears at least mid-2023, contrary to Mearsheimer's predictions, Russia and China seem to be getting closer regarding geopolitics and geoeconomics. On February 4th, Russian President Vladimir Putin met with Chinese President Xi face-to-face. The leaders convened in Beijing at the start of the Winter Olympics — and issued a lengthy statement detailing the two nations' shared positions on a range of global issues. The meeting happened shortly before the Russian invasion, and one could surmise that it was supposed to soften the possible adverse reaction from Beijing to the already prepared military operation by the Kremlin since Putin told Xi that Russia had designed a new deal to supply China with an additional 10 billion cubic metres of natural gas. Consequently, China abstained from a U.N. Security Council vote condemning the Russian invasion (Gerson, 2022).

Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development. Available at: http://en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5770#sel=1:21:S5F,1:37:3jE (Access 18.10.2023)

Andrew Krepinevich's Protracted Great-Power War

Andrew Krepinevich's “Protracted Great-Power War - A Preliminary Assessment work” published by the Centre for a New American Security, informs us about the American posture. Accordingly, "Now, however, with the rise of revisionist China and Russia, the United States is confronted with a strategic choice: conducting contingency planning for a protracted great-power conflict and how to wage it successfully (or, better still, prevent it from occurring), or ignoring the possibility and hoping for the best." (Krepinevich, 2020)

Among many valuable lessons that history can offer, one should remember that no country can wage a systemic war on its own on two fronts, hoping to be successful. Suppose both China and Russia are seen as strategic challengers to the American position in the international system. In that case, it follows logically that the U.S. needs to make one of them at least neutral (appease them) when in conflict with another. Given China's technological, economic, military, or population challenges, the most optimal choice would be to make Russia indifferent to American 'elbowing' in Central Asia or the Middle East vis-à-vis China. The price for such indifference also seems logical, and it is the dominance of the Russo-German tandem in Central and Eastern Europe and German dominance in the E.U. This would explain at least some developments in Europe regarding energy security, particularly President Biden's administration position on Nord Stream 2 and the not-so-much enthusiastic help to Ukraine from Germany.

However, recent developments seem to contrast such logical argumentation. President Biden's administration, as well as the leadership of the U.S. Armed Forces, seem to be committed to continuing the financial, technical and logistical support to Ukrainian President Zelensky's government for "as long as it takes" (the term frequently used in official speeches by Antony Blinken – The Secretary of State). According to the U.S. Department of Defence information (as of Feb 21, 2023), the U.S. committed security assistance to Ukraine in the form of 160 Howitzers, 31 Abrams tanks, 111 million rounds of small arms ammunition and four satellite communication antennas, among others. On top of that, Washington committed more than 30.4 billion U.S. dollars (only since the beginning of the Biden Administration) (U. S. Department of Defence, 2023). The U.S. is the leader of the coalition of many nations (54 to be exact) in efforts to counter the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This situation puts Washington in a predicament as, at least in the mediasphere, experts and former policymakers such as the former C.I.A. Director and U.S. Defence Secretary Leon Panetta does not shy away from identifying the existing state of affairs as a "proxy war" between the United States and the Russian Federation (Macmillan, 2022).

2 Importantly, Kremlin has been playing the “proxy war” card for some time in building its narrative regarding the ongoing “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine.

But is "Uncle Sam" still in a position to effectively challenge either Russia or China on their own? In 2001, French historian, sociologist, and political scientist Emmanuel Todd claimed that as of the beginning of the 21st century, the United States was no longer a solution to global problems; instead, it became one of the problems (Todd, 2003). The U.S. guaranteed political and economic freedoms for half a century. In contrast, today, they seem to be more and more an agent of international disorder, causing uncertainty and conflicts wherever they can. Given the geopolitical changes after 1989, the U.S. took for granted its position in the international system and decided to extend its interests across the globe. Surprisingly, perhaps for Washington, even traditional U.S. lies started to demand more independence (see the case of Germany and its role in southern Europe.) (Macron's idea of 'strategic autonomy') .

3 “Emmanuel Macron's comments about Taiwan and his call for European "strategic autonomy" sparked controversy as he advocated for the EU not to become followers of the US and China”. This parallels with President de Gaulle earlier calls for European strategic independence from American influence over European security (Lory, 2023).

According to Todd, given the actual balance of power globally, the U.S. would have to fulfill two conditions to maintain its hegemonic position. Firstly, it had to continue controlling its protectorates in Europe and Japan. Secondly, it had to finally eliminate Russia from the elite group of 'big powers', which would mean the disintegration of the post-Soviet sphere and the elimination of the nuclear balance of terror. None of these conditions have been met. Not being able to challenge Europe or Japan economically, the U.S. has also been unable to challenge the Russian nuclear position. Consequently, it switched to attacking medium powers such as Iran or Iraq economically, politically, and militarily engaging in 'theatrical militarism'. (Todd, 2003).

In contrast to the French historian, American political scientist Joseph Nye claims, "The United States will remain the world's leading military power in the decades to come, and military force will remain an important component of power in global politics." (Ney, 2019, p.70). He goes on to question whether the rise of China is going to spell the end of the American era: "[…] but, contrary to current conventional wisdom, China is not about to replace the United States as the world's largest economy. Measured in 'purchasing power parity' (P.P.P.), the Chinese economy became larger than the U.S. economy in 2014, but P.P.P. is an economists' measure for comparing welfare estimates, not calculating relative power. For example, oil and jet engines are imported at current exchange rates, and by that measure, China has a US$12 trillion economy compared to a US$20 trillion U.S. economy." […] “Power—the ability to affect others to get what you want—has three aspects: coercion, payment, and attraction. Economic might is just part of the geopolitical equation, and even in economic power, while China may surpass America in total size, it will still lag behind in per capita income (a measure of the sophistication of an economy).” (Ney, 2019, p.70).

And yet, as of 2023, America's economic components of her might seem to be very quickly eroding. After the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis and the consequent Covid-19 induced economic crisis, there are several woes on the horizon: Inflation has been rampant (that is one of the effects of federal stimulus after Covid-19), which makes the Federal Reserve continue to increase interest rates, making loans more and more expensive (Goldman, 2022). The stock market has been in the "sell-everything mode", which means the investors are losing a lot of money, so their trust in the economy is decreasing. Thirdly, this time around, the investors are not switching to bonds, which seems to confirm the previous point. Fourthly and finally, "none of this is happening in a vacuum. Russia continues its deadly invasion of Ukraine, which has choked off supply chains and sent energy prices through the roof. On top of that, a labour shortage has sent salaries surging and hindered the normal flow of goods worldwide (Goldman, 2022). Worse still, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis of the U.S. Department of Commerce, some of the key performance indicators regarding international trade are primarily negative (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2023). As of July 2022, experts debated whether the country was in a technical recession, whereas by now (mid-2023), the actual national debt had surpassed 31.46 trillion U.S. dollars (FiscalData.Treasury.gov, 2023).

The German-French engine of the European federalization?

The economic and political decrease of the U.S. and the parallel increase of China with Russia holding its position or even reclaiming its influence vis-à-vis NATO countries causes significant challenges to European powers and offers some ground-breaking opportunities. In terms of challenges, especially economically, Germany and France, as mentioned before, find themselves in a predicament.

The war in Ukraine has changed the European dynamics due to the pressure of the U. S. to support Ukraine and, consequently, the economic sanctions against The Russian Federation. Similarly, France and Germany have not been very happy with the economic sanctions against Russia and have continually tried to play down the possibility of an all-out EU vs Russia conflict. Listening to the speeches of Macron and Scholz, one cannot but hypothesize that Paris and Berlin would be content with the end of the war as soon as possible at any cost, to be born by Ukraine, to be able to come back to “business as usual.” Apparently, in an attempt to "escape forward", both European powers are proposing further steps to generate even more federal dynamics. Conversely, they suggest that concerning Foreign and Security Policy, the still observed voting pattern based on unanimity - one of the last strongholds of sovereignty, should be abolished, and the decisions should follow a qualified majority voting procedure. Notably, such arguments are made, invoking the potential gains for the EU as a geopolitical actor. In other words, countries such as Poland and Hungary would no longer be able to block Paris and Berlin from imposing their interests on the rest of the EU by presenting them as European. According to this vision, Hungary would no longer be able to ‘sympathize’ with Russia, and Poland would no longer be the ‘Trojan Horse’ of the U.S. interests in Europe in their game with Russia. And so, the war in Ukraine presents a perfect circumstance to call for a European federation. Germany has recently publicized such a vision. On August 24, 2022, Chancellor Olaf Scholz presented a speech at Charles University in Prague regarding his vision of the future of the EU at the beginning of the 3rd decade of the 21st century against the backdrop of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Experts, policymakers, and media pundits widely commented on the speech. It starts with an assertion that Russia is the biggest threat to the security of Europe. That fact produces two breakthrough consequences: firstly, Berlin has to pivot from Russia to its European Partners both economically and politically. Secondly, the European Confederation of equal States should morph into a European Federation (The Federal Government, 2022). Scholz’s vision includes four major ‘thoughts’. Firstly, given the further enlargement of the European Union for up to 36 states, a transition should be made to majority voting in common foreign or tax policy. Secondly, regarding European sovereignty, “we grow more autonomous in all fields; that we assume greater responsibility for our own security; that we work more closely together and stand yet more united in defence of our values and interests around the world.”. In practical terms, Scholz singles out the need for one command and control structure of European defence efforts (European army equipped chiefly by French and German Companies?). Thirdly, the EU should take more responsibility (at the expense of national governments) regarding migration and fiscal policy against the backdrop of the economic crisis induced by Covid-19 pandemic. This, in practical terms, means, according to Scholz, one set of European debt rules to attain a higher level of economic integration. Finally, some disciplining. “We, therefore, cannot stand by when the principles of the rule of law is violated, and democratic oversight is dismantled. Just to make this absolutely clear, there must be no tolerance in Europe for racism and antisemitism. That’s why we are supporting the Commission in its work for the rule of law.

Conclusion

The war in Ukraine is arguably proof of the region's role in the security and stability of Europe and its economy. Food supplies, mostly various harvests and energy, are a case in point. On top of that, the region has a lot of raw materials. Ukraine has large deposits of 21 of 30 such materials critical in European green transformation (Ukrinform, 2023). Before the war in Ukraine began, in July 2021, the EU and Ukraine signed non less than a strategic partnership on raw materials. The partnership includes three areas from the approximation of policy and regulatory mining frameworks, through a partnership that will engage the European Raw Materials Alliance and the European Battery Alliance to closer collaboration in research and innovation along both raw materials and battery value chains using Horizon Europe (European Commission, Press Release 2021).

As for security, in a traditional sense, the U.S. is involved with Ukraine regarding nuclear weapons. In the letter from March 17, 2023, the director of the Energy Department’s Office of Nonproliferation Policy, Andrea Ferkile, tells Rosatom’s director general that the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant in Enerhodar “contains US-origin nuclear technical data that is export-controlled by the United States Government” (Bertrand, Lister, 2023). Worse still, The Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, Victoria J. Nuland, admitted in her testimony on Ukraine in the US Congress that, indeed, “Ukraine has biological research facilities, which we are now quite concerned Russian troops, Russian Forces, may be seeking to gain control of, so we are working with the Ukrainians on how they can prevent any of those research materials from falling into the hands of Russian forces should they approach” (C-Span, 2022).

4 See more at: https://www.state.gov/energy-security-support-to-ukraine/ (Access 18.10.2023)

As Scott and Alcenat claim, the analysis of the competitive policies of each great power confirms the Heartland concept's importance. They project the utility of Mackinder’s analysis to Central Asia, asserting that: “it is valid in today’s foreign policy and policy analyses. Each power strives for control of or access to the region’s resources. For China, the primary goal is to maintain regional stability as a means for border security and assurance of stable economic relations. For the European Union, the main goal is to gain economic access while simultaneously promoting the democratization of those countries that are politically unstable.” (Scott, Alcenat, 2008).

5 Senior Colonel Zhou Bo (retired) - a senior fellow of the Centre for International Security and Strategy at Tsinghua University and a China Forum expert, a former director of the Centre for Security Cooperation of the Office for International Military Cooperation of the Ministry of National Defence of China offered a similar evaluation: “the competition between the two giants (U.S.A. and China) will not occur in the Global South, where the US has already lost out to China. At the same time, in the Indo-Pacific, few nations want to take sides. Instead, it will be in Europe, where the U.S. has most of its allies, and China is the largest trading partner” (Bo, 2023).

References

Bertrand, N. and Lister, T. (2023) “US warns Russia not to touch American nuclear technology at Ukrainian nuclear plant”, CNN Politics, 19.04. Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2023/04/18/politics/us-warns-russia-zaporizhzhia-nuclear-plant/index.html (Access 18.10.2023)

Brzozowski, A. (2022) “Ukraine war is 'birth of geopolitical Europe', E.U. top diplomat says.” Euroactiv, 1.03. Available at: https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/ukraine-war-is-birth-of-geopolitical-europe-eu-top-diplomat-says/ (Access 18.10.2023)

Bureau of Economic Analysis of the U.S. Department of Commerce (2023) U.S. Economy at the Glance. Available at: https://www.bea.gov/news/glance (Access 18.10.2023)

Bo, Zh. (2023) “The true battleground in the US-China cold war will be in Europe”, South China Morning Post, 2.05. Available at: The true battleground in the US-China cold war will be in Europe | South China Morning Post (scmp.com) (Access 18.10.2023)

C-Span (2022) US biolabs confirmed in Ukraine. Available at: https://www.c-span.org/video/?c5005055/user-clip-biolabs-confirmed-ukraine (Access 18.10.2023)

Dunlop, J. B. (1997) “Aleksandr Dugin's Foundations of Geopolitics.” Stanford. The Europe Centre. Freeman Spogli Institute and Stanford Global Studies. Available at: https://tec.fsi.stanford.edu/docs/aleksandr-dugins-foundations-geopolitics (Access 18.10.2023)

U. S. Department of Defence (2023) Support for Ukraine. Available at: https://www.defense.gov/Spotlights/Support-for-Ukraine/ (Access 18.10.2023)

European Commission, Press Release (2021). “EU and Ukraine kick-start strategic partnership on raw materials” 13 July 2021, Available at: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-and-ukraine-kick-start-strategic-partnership-raw-materials-2021-07-13_en (Access 18.10.2023)

FiscalData.Treasury.gov (2023) “What is the national debt?” Available at: https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/national-debt/ (Access 18.10.2023)

Gerson, J. and Klare, M. (2022) “Is ‘Taiwan Next’ No Sign of Sino-Russian Coordination over Ukraine or Preparations an Invasion of Taiwan". Available at: Is "Taiwan Next"? No Sign of Sino-Russian Coordination over Ukraine or Preparations for an Invasion of Taiwan — Committee for a SANE U.S.-China Policy (saneuschinapolicy.org) (Access 18.10.2023)

Goldman, D. (2022) “4 reasons the economy looks like it's crumbling — and what to do about it”. May 14, 2022 Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2022/05/14/economy/recession-signs/index.html (Access 18.10.2023)

Johnson, K and Gramer, R. (2020) “The Great Decoupling” foreignpolicy.com, Available at: http://acdc2007.free.fr/greatdecoupling620.pdf (Access 18.10.2023)

Kapo, A. (2021). “Mackinder: Who rules Eastern Europe rules the World.” Institute for Geopolitics, Economy and Security, February 8, 2021. Available at: https://iges.ba/en/geopolitics/mackinder-who-rules-eastern-europe-rules-the-world/ (Access 18.10.2023)

Krepinevich, A. Jr. (2020) “Protracted Great-Power War. A Preliminary Assessment”. Available at: https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/protracted-great-power-war (Access 18.10.2023)

Lory, G. (2023) “Is Macron's idea of 'strategic autonomy' the path to follow for E.U. relations with the U.S.?” Euronews, April 13, 2023. Available at: https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2023/04/13/is-macrons-idea-of-strategic-autonomy-the-path-to-follow-for-eu-relations-with-the-us (Access 18.10.2023)

Mackinder, H. (1919) Democratic Ideals and Reality. A study in the politics of reconstruction. London: Constable and Company L.T.D.

Mackinder, H. (1943) “The round world and the winning of the peace”, Foreign Affairs, Vol 21(2), (July), p. 600.

Macmillan, J. (2022) “With NATO and the U.S. in a 'proxy war' with Russia, ex-CIA boss Leon Panetta says Joe Biden's next move is crucial". A.B.C. News, 25.03. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-25/nato-us-in-proxy-war-with-russia-biden-next-move-crucial/100937196 (Access 18.10.2023)

Mearsheimer, J. (2013) The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: W.W. Norhon & Company 2nd Edition.

National Security of the United States of America (2017) The White House: Washington. Available at: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905-2.pdf (Access 18.10.2023)

Ney, J. S. Jr. (2019) “The rise and fall of American hegemony from Wilson to Trump.” International Affairs Vol 95(1), pp. 63-80

Osborn, A. (2022) “Russia's Putin authorises 'special military operation' against Ukraine.” Reuters, 24.02. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-putin-authorises-military-operations-donbass-domestic-media-2022-02-24/ (Access 18.10.2023)

Scott, M and Alcenat, W. (2008) “Revisiting the Pivot: The Influence of Heartland Theory in Great Power Politics.” Macalester College, 09.05. Available at: https://www.creighton.edu/fileadmin/user/CCAS/departments/PoliticalScience/MVJ/docs/The_Pivot_-_Alcenat_and_Scott.pdf (Access 18.10.2023)

Sloan, G. (2017) Geopolitics, Geography and Strategic History. London: Routledge.

Soldatkin, V. and Aizhu, Ch. (2022) “Putin hails $117.5 bln of China deals as Russia squares off with West.” Reuters, 04.02. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/putin-tells-xi-new-deal-that-could-sell-more-russian-gas-china-2022-02-04/ (Access 18.10.2023)

The Federal Government (2022) Speech By Federal Chancellor Olaf Scholz at The Charles University In Prague On Monday, 29 August 2022. Available at: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/scholz-speech-prague-charles-university-2080752 (Access 18.10.2023)

Todd, E. (2003) Schyłek imperium. Rozważania o rozkładzie systemu amerykańskiego. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Akademickie Dialog.

Ukrinform (2023) Ukraine has deposits of 21 raw materials critical to EU Available at: https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-economy/3280369-maasikas-ukraine-has-deposits-of-21-raw-materials-critical-to-eu.html (Access 18.10.2023)