Emerging global AI order: a comparative analysis of US and China's AI strategic vision

by Hammad Gillani

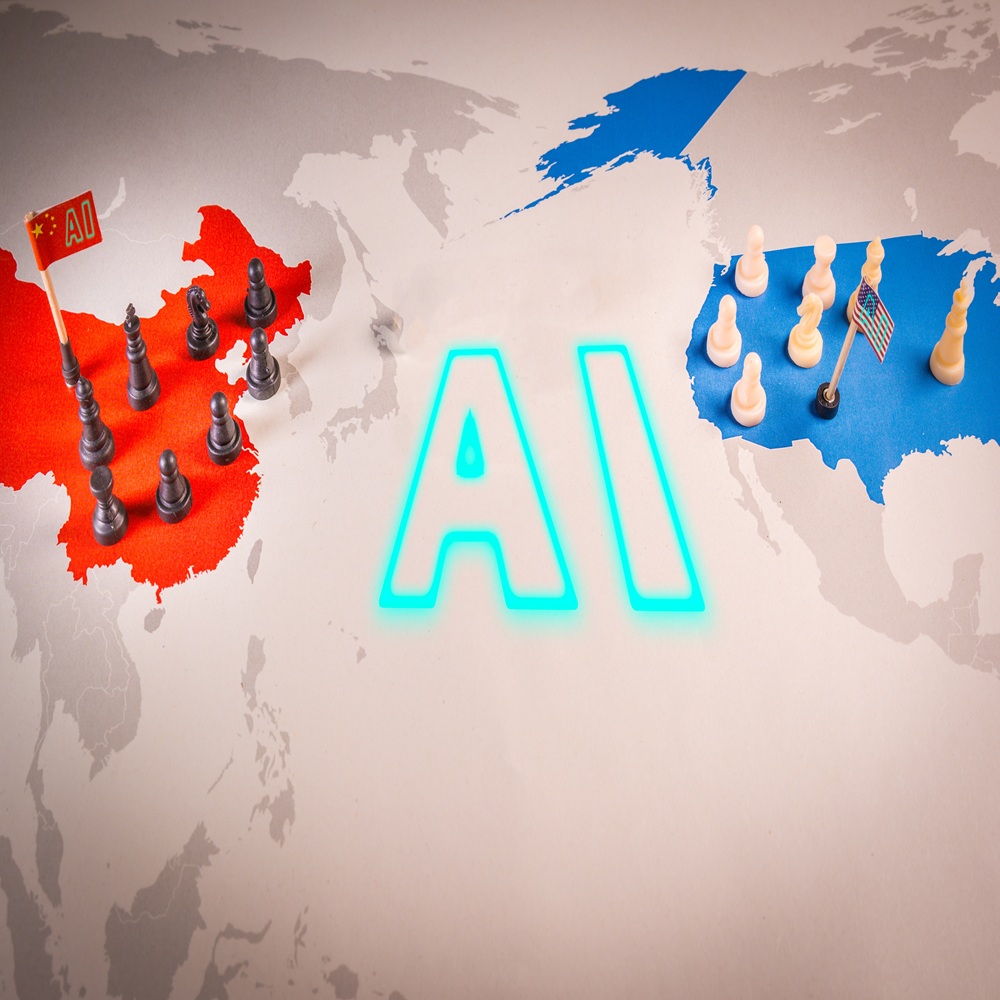

Introduction The 21st century global politics has now taken a new shape with the advent of artificial intelligence (AI). The traditional nature of great power rivalry revolves around military maneuvers, defensive-offensive moves, and weapons deployment to challenge each other, maintaining their respective hegemony over the international arena. The revival of artificial intelligence has reshaped the conventional great power game.(Feijóo et al. 2020) From now onwards, whenever the strategic circles discuss the security paradigm, AI has to be its part and parcel. The emergence of AI has altered the status quo, where major powers are now shifting towards AI-based technology. As the most basic function of AI is to create such machines and platforms that can perform tasks more proficiently than humans, it has the ability to enhance decision-making, increase efficiency, and reduce the likely risk of human errors. But at the same time, risks are also lingering. The United States (US) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) are considered to be the main players of great power politics. Their rivalry has long been centered around territorial conflicts and maritime contests. With the PRC claiming most of the territories in the South China Sea and East China Sea, the US, under its Indo-Pacific Strategy (2022), has challenged the Chinese assertion.(Hassan and Ali 2025) But what the world has witnessed is that both economic hegemons have been avoiding any direct military conflict with each other. The most prominent area where both the US and the PRC are now in a continuous competition is the technological domain. China has always maintained an edge over the US in the respective field due to the fact that it holds most of the world’s known rare earth minerals—a key to technological superiority. Through trade barriers, i.e., tariffs, quotas, etc., and restricting trade with prominent Chinese companies, the US has always tried to contain technological developments in China.(Wang and Chen 2018) “The reality is that both China and the United States are focused on getting the infrastructure necessary to win the so-called AI race. Now, whether it’s actually a race is a separate question, but data, energy, and human capital are all critical inputs to this. The massive investment infrastructure is top of mind for leaders in both countries as they seek to do it. China’s access to the advanced technology and semiconductors is going to be a key cornerstone in this regard.”(Sacks, 2025) US and China have placed AI at the center of their national policies and global strategies. Both have been introducing various policy papers, strategies, and action plans for the advancements in the field of artificial intelligence and how to counter the side. Now, the international arena is witnessing two parallel AI setups: one created by the US and the other by China. As both are tremendously investing in research, development, and innovation in artificial intelligence, their national narratives and global plans are competing with each other, further exacerbating the international AI landscape. This paper aims to critically analyze key policies highlighted under the national action plans and strategies launched by the US and the PRC, respectively. Applying the theoretical lens of constructivism, which deals with the role of ideas, norms, and values in shaping the international system, the paper will demonstrate key differences between the AI strategies of the US and China and how their ideological beliefs shape their respective AI policies. Moreover, the analysis will provide expert views on the future landscape of the AI race, its relation to the Great Game, and its political, economic, and military repercussions for the rest of the world. Furthermore, the analysis will mostly rely on expert interviews, key excerpts from official administrative documents, and research findings. This study will also provide insights into the Trump 2.0 administration’s policy outlooks vis-à-vis Beijing’s National AI policy. America’s AI Action Plan 2025 President Trump unveiled his administration’s national strategy on artificial intelligence on 23rd July 2025. Entitled as “Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan”, this strategy is a long-term road map to counter and contain China’s growing profile in the tech world, in particular the AI.(White House, 2025) The title of the strategy explicitly announces that the US has entered into the global AI race. Under this strategy, the United States does not want to eliminate China, rather the US desires to lead the AI world as a core nation, while the PRC should operate as a periphery nation. On July 15 2025, while addressing the AI Summit in Pittsburgh, President Donald Trump stated, “The PRC is coming at par with us and we would not let it happen. We have the great chips and we have everything great. And, we will be fighting them in a friendly fashion. I have a great relationship with President Xi and we smile at the back and forth, but we are leading…...”(AFP, 2025) America’s AI Action Plan: Key Pillars A. Accelerate AI Innovation This first pillar of the AI national strategy by the US deals with the fact that AI should be integrated into every sector of American lives. From the grassroots level to the national or international level, the US should be a leading AI power. AI innovation states that any type of barrier, i.e., legal, regulatory, or domestic constraints, must be eradicated at first to promote, enhance, and boost AI innovation in the US. The strategy clearly states the innovation in artificial intelligence to be the fundamental step towards AI global dominance. The American beliefs, values and norms hold much significance in this regard. This strategy laid down the framework where AI platforms and models should have to align with the US democratic principles, including free speech, equality, transparency, and recognition. This means that the US AI action plan will operate under the umbrella of capitalist ideology.(White House, 2025) Another most important feature in the field of AI innovation is the conglomeration of public-private ventures. Both the governmental authorities and public institutions are provided with such policies and frameworks to integrate AI platforms into their day-to-day operations. Creating an AI ecosystem is the cornerstone of this strategy.(White House, 2025) It aims to build an American workforce mastered in AI capabilities, defense forces and their key platforms integrated with AI, and provide a secure and safe environment to national and international investors, thus encouraging them to increase their investments in the US. Last but not least, the development of various departments countering the unethical use of AI, i.e., deep fakes, thus securing the national sovereignty and integrity of the homeland. Principal Deputy Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), Lynne Parker, while highlighting the significance of the US 2025 AI Action Plan, stated, “The Trump Administration is committed to ensuring the United States is the undeniable leader in AI technology. This plan of action is our first move to enhance and preserve the US AI interest, and we are eager to receive our public perception and viewpoints in this regard.”(House, 2025) The AI innovation drive is indicative of the US being a liberal-democratic and entrepreneurial society. It has an innovation culture that focuses on open research, leadership in the private sector, and ethics based on its national myth of freedom, individualism and technological optimism. B. Building the AI Infrastructure This is the most crucial pillar of the US AI Action Plan 2025. From propagating the idea of AI innovation, the next step is to build a strong, secure, and renowned infrastructure to streamline the policy guidelines highlighted in the national AI strategy. This includes the development of indigenous AI factories, companies, data facilities, and their integration into the American energy infrastructure. The most significant step highlighted in this pillar is the construction of indigenous American semiconductor manufacturing units.(White House, 2025) Now what does it mean? As of today, China is considered to be the center of semiconductor manufacturing. Semiconductors are the basic units of any technology, i.e., weapons, aircraft, smartphones, etc. The US has long been importing semiconductor chips from China. Integration of the US energy infrastructure with that of the AI facilities is the ultimate objective of this strategy. Immense energy-producing units, i.e., electricity, under the ‘National Energy Emergency Act’ would be established to provide a continuous supply of electricity to AI data centers and facilities without any hindrance.(House, 2025) But the Trump 2.0 administration, under its protectionist policies, aspires to restrict imports from China and build a domestic semiconductor processing unit. Highlighting the American dependence on Chinese chips, the American chemist and politician John Moolenaar stated, “The Trump administration has made one thing abundantly clear: we must reassert control over our own economic destiny. That’s not isolationism; that’s common sense. The Chip Security Act, outbound investment restrictions, and stronger export controls—those aren’t closing ourselves off. They are about ensuring America isn’t subsidizing or facilitating our own decline. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is using American capital to fund aircraft carriers, fighter jets, and AI systems that target our allies and threaten our freedoms.”(Moolenaar, 2025) The norm of decentralized innovation is applied in developing the infrastructure, and it empowers universities, startups, and private corporations. This is an expression of confidence in market mechanisms and civil liberties, which is in line with its social values of open innovation and competition. C. AI Diplomacy and Security The last pillar of the US AI national action plan is to collaborate with international partners and allies. This simply means to export American AI technology to strategic partners and those with common interests. This will, as a result, give rise to new types of groupings known as ‘AI Alliances.”(White House, 2025) The Global Partnership on AI (GPAI), QUAI AI Mechanism, and US-EU Trade and Technology Council are some of its best manifestations. Like the security and defense partnerships, the AI alliances will enable the US and the West to encircle the PRC in the tech world, where strong western collaborations and partnerships would hinder the PRC from becoming the tech giant or from excelling in AI production. It Encourages responsible AI governance and a democratic form of AI standards of the US, which are based on its self-perception as a global governor of the liberal values. Thus, in order to enhance AI-related exports to allies, the US has established various institutions, including the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). The US AI diplomacy aims to counter China’s growing footprints in the international bodies and institutions.(State 2023) As these global bodies are a key to spreading particular norms and values, shaping the public perception, and framing the global order, the US wants to challenge Chinese entrenchments in these organizations through political and diplomatic coalitions and groupings. Doing this, the West will be able to propagate their version of the global AI order. This means capitalism vs. communism will now be clearly visible in the global AI race between the economic hegemons. The US Vice President J.D. Vance, while addressing the European Union (EU) leaders in Paris explicitly stated, “The US really wants to work with its European allies. And we wish to start the AI revolution with an attitude of cooperation and transparency. However, international regulatory frameworks that encourage rather than stifle the development of AI technology are necessary to establish that kind of trust. In particular, we need our European allies to view this new frontier with hope rather than fear.”(Sanger 2025) In case of security, the strategy aims to establish various AI Safety Institutes (AISIs) to reduce or eliminate the risk of AI-related accidents, which include errors in AI platforms, most specifically in the AI-operated weapon systems, and the unethical use of AI programs, i.e., generative AI or LLMs. Similarly, the strategy emphasized the danger posed by the non-state actors. These violent actors must be restrained from acquiring such advanced yet sophisticated technology.(White House, 2025) China’s New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan For the first time in July 2017, the PRC launched its long-term national AI vision 2030, entitled “New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan,” which is comprised of all the policies, guidelines, and measures to be taken by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to foster its AI developments.(Council 2017) China’s AI 2030 vision is none other than the extension of the idea that President Xi Jinping circulated in 2012 regarding China’s future role in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI). This strategy aims to strengthen China’s AI footprints in the international arena. Ranging from investments to infrastructure, this plan of action explicitly declared to develop the PRC into the hub of AI innovation and investment by 2030. This plan of action is determined to bring about a profit of $160 billion by 2030.(O’Meara 2024) While addressing the Politburo Study Session on 25th April 2025, the Chinese President Xi Jinping noted, “To gain a head start and secure a competitive edge in AI, it is a must to achieve breakthroughs in basic theories, methodologies, and tools. By leveraging AI to drive the transformation of scientific research paradigms, we can speed up achieving breakthroughs in scientific and technological innovation in all sectors.”(Agency 2025) China’s AI Vision 2030: Key Objectives A. AI Leadership (2020) The PRC has successfully accomplished this objective. Under this pillar, China has established significant AI infrastructure, including key facilities and data centers, coming at par with the US. Within this, the CCP urged the academic institutions to promote, enhance, and foster research in the AI domain, which resulted in the major developments in the sectors of big data, swarm intelligence, and super artificial intelligence.(Council 2017) China has successfully established its domestic AI industrial complex worth $22 billion. Various educational institutions, i.e., Tsinghua, Peking, etc., and major companies, i.e., Baidu, iFlyTek, etc., have now completely transformed into AI hubs where research, innovation, and practices are conducted through highly advanced AI platforms. Commenting on the US-China AI leadership contest, Dr. Yasar Ayaz, the Chairman and Central Project Director of the National Center for AI at NUST, Islamabad, explicitly remarked, “Efficiency is the new name of the game now. Chinese AI inventions and developments clarify the fact that even with the smaller number of parameters, you could achieve the same kind of efficiency that others with an economic edge are achieving.”(Ayaz 2025) The AI leadership symbolically builds the socially constructed narrative of the Chinese Dream and national rejuvenation into the need to overcome the century of humiliation and take its place in the world order. Here, AI leadership is not just a technical objective but a discursive portrayal of the Chinese self-concept of being a technologically independent and morally oriented civilization. B. AI Technology (2025) The second most important objective of China’s AI Vision 2030 is to reach a level of tech supremacy in the international arena by 2025. Major work areas include localization of chip industries, advancements in semiconductors and robot manufacturing, etc. The first phase of 2020 basically laid the infrastructural foundation of the plan, while this phase deals with the development and innovation of key AI-operated platforms, including robots, health equipment, and quantum technology.(Council 2017) Another most crucial feature of the 2025 phase is to establish various AI labs throughout mainland China. This would result in the integration of AI into different public-private sectors, i.e., finance, medical, politics, agriculture, etc. Last but not least, a civil-military collaboration is described to be a cornerstone in this regard. The AI-operated platforms would be utilized by both civil and military institutions, thus preserving the PRC’s national security and safety. Giving remarks over China’s technological edge, Syed Mustafa Bilal, a technology enthusiast and research assistant at the Centre for Aerospace and Security Studies (CASS), added, “China, which for the longest time has been criticized for having a technologically closed-off ecosystem, is now opting for an open-source approach. That was evident by the speeches of Chinese officials at the Global AI Action Summit, in which they tried to frame China’s AI strategy as being much more inclusive as compared to the West. And one illustration of that is the ironic way in which deep search is currently furthering OpenAI's initial selfless objective of increasing AI adoption worldwide.”(Bilal 2025) Thus, the AI vision of China reflects ideational promises of social order, central coordination, and a moral government, ideals that are based on its political culture and civilization background. C. AI Innovation Hub (2030) By 2030, China aims to be at the epicenter of global AI innovations, development, and investments. The PRC’s political, economic, and defense institutions will be governed under AI overhang. The most significant feature of this phase is to counter the US-led AI order by challenging the US and the West in various international bodies like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). The main tenet of China’s 2030 vision is to transform it into a completely AI-driven economy—an AI economic giant.(Council 2017) As the PRC is ruled by the communist regime of President Xi Jinping, China aspires to counter the Western-led AI order through instigating its communist values, including high surveillance, strict national policies, and population control. By avoiding a completely liberal, free speech AI environment in mainland China, the CCP aims to come on par with the US by having authoritative control over its people, thus maintaining its doctrine of ‘techno self-reliance.’ Giving his insights on the new global AI order and the ideological rift between the US and China, Dr. Wajahat Mehmood Qazi, advisor on AI and digital transformation to the private tech companies and faculty member at the COMSATS University, Lahore, explicated, “Yes, there is a digital divide, but the interesting part over here is this: the world is evolving, so this big divide is no more about the decentralization or the centralization. If we look at how China is promoting openness by releasing its foundation models, at the same time the ecosystem of their LM models or AI is still in close proximity. Whereas, the western world is having a different narrative. They are talking about the openness of the models, but at the same time it’s more market-driven. In my view, we are entering into a world where innovation requires openness and closed methods simultaneously.”(Qazi 2025) The concept of innovation with Chinese features is used to describe a socially constructed attempt to exemplify another approach to technological modernity, which combines dictatorial rule and developmental prosperity. It is a mirror image of self-concept in China as a norm entrepreneur that wants to legitimize its system of governance and impact the moral and technological discourse of AI at the global scale. Conclusion The constructivist perspective informs us that the competition between Washington and Beijing is not predetermined; it is being conditioned by the perceptions, suspicion, and competing versions that can be rebuilt through dialogue and mutual rules. The ideological divide can be overcome by creating inclusive tools of AI governance, with transparency, ethical principles, and shared responsibility in their focus. The common ground created through the establishment of a mutual conception of the threats and the ethical aspects of AI will enable the United States and China to leave the zero-sum game on AI and enter into a model of normative convergence and accountable innovation. Constructivism thereby teaches us that cooperation in AI is not just a strategic requirement but also a social option, which is constructed on shifting identities and the recognition of global interdependence with each other. The great power competition is now in its transformative phase, bypassing the traditional arms race for a more nascent yet powerful AI race. In the context of the US-China contest, administrations on both sides are trying their utmost to launch, implement, and conclude critical national strategies and formulations in the field of artificial intelligence. Both are moving forward at a much greater pace, thus developing advanced technologies in the political, economic, and military domains. Be it China’s Deep Seek or the Western Chat GPT, be it Trump’s Stargate project or Xi’s AgiBot, both are investing heavily into the tech-AI sector. Despite this contest, both economic giants also need joint efforts and collaborations in various matters of concern. Until now, it’s been very difficult to declare which will lead the global AI order. The chances of a global AI standoff are there.ReferencesAFP. 2025. “Trump Vows to Keep US Ahead in AI Race with China.” The News International. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/1328672-trump-vows-to-keep-us-ahead-in-ai-race-with-china.Agency, Xinhua News. 2025. “20th Collective Study Session of the CCP Central Committee Politburo.” Center for Security and Emerging Technology, 1–3.Ayaz, Dr. Yasar. 2025. “Global AI Rivalry: U.S vs China.” PTV. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_82MMzI_g2c&t.Bilal, Syed Mustafa. 2025. “Global AI Rivalry: U.S vs China.” PTV. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_82MMzI_g2c&t.Council, State. 2017. “Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan.https://digichina.stanford.edu/work/full-translation-chinas-new-generation-artificial-intelligence-development-plan-2017/.Feijóo, Claudio, Youngsun Kwon, Johannes M. Bauer, Erik Bohlin, Bronwyn Howell, Rekha Jain, Petrus Potgieter, Khuong Vu, Jason Whalley, and Jun Xia. 2020. “Harnessing Artificial Intelligence (AI) to Increase Wellbeing for All: The Case for a New Technology Diplomacy.” Telecommunications Policy 44 (6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2020.101988.Hassan, Abid, and Syed Hammad Ali. 2025. “Evolving US Indo-Pacific Posture and Strategic Competition with China.” Policy Perspectives 22 (1). https://doi.org/10.13169/polipers.22.1.ra4.House, White. 2025. “Declaring a National Energy Emergency – The White House.” Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/declaring-a-national-energy-emergency/.House, White. 2025. “Public Comment Invited on Artificial Intelligence Action Plan – The White House.” Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/02/public-comment-invited-on-artificial-intelligence-action-plan/.Moolenaar, John. 2025. “The 2025 B.C. Lee Lecture Featuring Congressman John Moolenaar.” Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QIIUZlaKofU.O’Meara, Sean. 2024. “China Ramps Up AI Push, Eyes $1.4tn Industry By 2030.” Asia Financial. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.asiafinancial.com/china-ramps-up-ai-push-eyes-1-4tn-industry-by-2030-xinhua.Qazi, Dr. Wajahat Mehmood. 2025. “Global AI Rivalry: U.S vs China.” PTV. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_82MMzI_g2c&t=.Sacks, Samm. 2025. “China’s Race for AI Supremacy - YouTube.” Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xaccSxP8pOQ&t=8s.Sanger, David E. 2025. “Vance, in First Foreign Speech, Tells Europe That U.S. Will Dominate A.I.” THe NewYork Times. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/11/world/europe/vance-speech-paris-ai-summit.html.State, US Department of. 2023. “Enterprise Artificial Intelligence Strategy,” no. October, 103–13. https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Department-of-State-Enterprise-Artificial-Intelligence-Strategy.pdfWang, You, and Dingding Chen. 2018. “Rising Sino-U.S. Competition in Artificial Intelligence.” China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 4 (2): 241–58. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2377740018500148.White House. 2025. “Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan.” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Americas-AI-Action-Plan.pdf