Diplomacy

India 2024: anatomy of an election

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Diplomacy

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Apr.06,2024

May.27, 2024

Last March 16th, the Election Commission of India informed the public media about the schedule for the upcoming legislative elections in the country for the period 2024-2029. However, this announcement does not mark the beginning of the Indian electoral process, as since 2023, different national political parties had been shaping their candidates and, in some cases, initiating their political campaigns in preparation for the elections. The schedule, announced by the electoral authority, is divided into seven phases, and will be extended from April 19th, 2024, until June 1st of the same year, with vote counting taking place on June 4th. India’s independence from the British Colonial Empire in 1947 marked the beginning of a profound process of political, economic, and social transformations that determined the life of the society and the surrounding countries. The founding fathers of the country, not without setbacks, promoted the drafting and subsequent approval of a constitution that recognized the secular character of the country, reinforcing the idea of a multicultural, multi-ethnic, multilingual, and multi-religious India. Additionally, in the text, the foundations of the country's political system were declared, and consequently, its electoral system.

India is a federal parliamentary democratic republic, so its political system is a combination of the parliamentary and presidential systems with a greater emphasis on the parliamentary system, where the President is the head of state, and the Prime Minister is the head of government. The President is elected by an Electoral College composed of members of Parliament and cannot act without the approval of the Council of Ministers, who are chosen by the Prime Minister. This is why the Prime Minister is more important than the President. The Indian Parliament is bicameral, meaning it consists of the ‘Lok Sabha’ (House of the People or Lower House) and the ‘Rajya Sabha’ (Council of States or Upper House). The ‘Rajya Sabha’ comprises 238 members, representing the States and the Union Territories, and 12 members designated by the President. Candidates are elected by the Legislative Assembly of the States and Union Territories through the single transferable vote system via proportional representation. On the other hand, the Members of Parliament of the ‘Lok Sabha’ are elected every five years directly by the electorate; the Prime Minister is typically the leader of the party with the most seats in the ‘Lok Sabha’. The party which has the majority of the 543 seats in the Lower House of Parliament can form a government and appoint a Prime Minister from among its winning candidates. In case that no party holds a simple majority, different parties form coalitions until they acquire the necessary number of seats to elect a Prime Minister. [1] While some alliances are formed before elections, many alliances are negotiated after results are announced and may even change during a government's term. The legal framework to conduct elections specifies that the supervision, direction, control, preparations, and behavior of the elections shall be established in the Election Commission, independently of the incumbent government (Article 324). The Election Commission also establishes the principle of adult suffrage (Article 326) and makes a general stipulation regarding the reservation of seats for backward castes, tribes, and the so-called Anglo-Indians (Articles 330-333). A person is qualified to be a candidate for election if they are over 25 years old for the ‘Lok Sabha’ and 30 for the ‘Rajya Sabha’, in addition to being a voter in a parliamentary constituency (Times of India, 2024b). The seats are distributed among the states in proportion to their population: more people mean more seats. Approximately 25% of the seats are constitutionally reserved for members from two disadvantaged communities: the Scheduled Castes (SC), also known as Dalits, and the Scheduled Tribes (ST), which represent India’s tribal populations or Adivasis. Eighty-four seats are reserved for SC candidates, and forty-seven seats are reserved for ST candidates (Times of India, 2024a). In these electoral constituencies, only candidates from the protected groups can participate in the elections, although all eligible adults can cast their votes. Although the Indian Parliament recently passed a new measure to reserve one-third of legislative seats for women, the implementation of this law has been postponed until after 2024.

India’s unique characteristics make any political process there highly complex. The extensive geographical dimension, the contrasts between different climates and terrains, the remote nature of settlements, especially in mountainous regions, and the challenge posed by large, overpopulated cities, make election, whether state or general, become an event of immense proportions. In fact, general elections in India are considered the largest political, democratic, and logistical exercise in the world. In the electoral process of 2014, according to the numbers published by the Pew Research Center, there were 788 million voters, including nearly 150 million who would have been eligible to vote for the first time. In a survey conducted by the same Center between December 2013 and January 2014, the Indian public, by a three-to-one margin, preferred the BJP over the then-ruling INC. Additionally, 60% of the respondents stated they had a very favorable opinion of Modi, while only 23% held the same opinion about Rahul Gandhi, the INC candidate (Stokes, 2014). From April 7th to May 12th, 2014, the Sixteenth General Elections were held in India, they were divided into ten stages across the country's 35 states and Union Territories. Voting took place for representatives from 543 constituencies, with 412 for the general population (General), 84 for the Scheduled Castes, and 47 for the Scheduled Tribes. The total number of candidates for these constituencies was 8,251, of which 7,577 were men, 668 were women, and 6 were "others". The average number of candidates per constituency was 15. There were 927,553 polling stations distributed across the country. The electoral roll consisted of 834,082,814 citizens, with 553,020,648 voters participating, reaching an effective electoral participation rate of 66.30% (Moreno Hernández, 2015). The BJP campaign, which presented Narendra Modi for the first time as its strongest candidate for Prime Minister of the country, was characterized by building an image around Modi as the "development man" — the man who would facilitate comprehensive development in India, having successfully implemented his governance model for over 10 years as Chief Minister in Gujarat. The campaign capitalized on popular discontent and sought to focus its message on the upper and middle classes, as well as the youth, through a developmental discourse that extensively utilized information technologies such as social media and unprecedented media bombardment in India at that time. Modi personally addressed over 400 rallies in a span of 7 months, traveling more than 300,000 kilometers to participate in nearly 200 campaign events, while the holographic projections of his figure and broadcasts of his speeches reached nearly all Indian constituencies (Muralidharan, 2014), effectively transforming the parliamentary campaign into what resembled a presidential-style elections. On May 16th, 2014, the total vote count was conducted. The results showed the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), led by the BJP, as the clear winner, securing most of the constituencies, specifically 336 out of 543, which represents 61.8% of the total seats. It is noteworthy that the BJP alone won 282 seats, accounting for 31.34% of the total votes, meaning that out of the 834,082,814 citizens eligible to vote, only 171,660,230 decided to cast their ballots in favor of the BJP. However, the indisputable victory of the right-wing requires a deeper analysis, as the outcome in 2014 does not compare to the 1984 elections when the Congress Party won 414 seats. This highlights the need for caution when referring to the "orange wave" as a pan-Indian phenomenon (Moreno Hernández, 2015). Voter turnout in Indian elections tends to be high: the parliamentary elections of 2019 saw a 67% turnout of the total eligible population. Votes are cast electronically in over a million polling stations, requiring around 15 million employees during voting. To reach all possible voters in villages and isolated islands in the Himalayas, electoral officials travel by any means available, including trains, helicopters, horses, and boats. In 2019, the elections took place in seven phases between April 11th and May 19th, with all votes being counted on May 23rd. Typically, the first phase of elections is held in a specific set of geographic regions, and subsequent phases gradually move across the country to cover other regions. Without primary elections, party leaders have complete control over the nomination of their candidates. If candidates fail to secure the party endorsement, they may run as independents, putting them at a disadvantage compared to party-backed candidates. Out of 543 Members of Parliament elected in 2019, only four were independent candidates (Roy-Chaudhury, 2019). While they are considered the elections with the highest number of voters in the world, due to being the most populous country globally, this exercise is also considered one of the most expensive. According to studies, in the 2019 elections, political parties spent over $7 billion. Specifically, parties and candidates spent approximately $8.7 billion to attract more than 900 million eligible voters (Roy-Chaudhury, 2019). Regarding the total number of candidates fielded and the electoral roll, in 2019, 8,054 candidates representing 673 parties contested the elections to have the opportunity to become Members of Parliament. Nearly 615 million people (67.4% of Indians) voted in 2019: this was the highest voter turnout recorded. For the first time in history, the persistent gender gap between male and female participation disappeared. In these elections, the ‘Bharatiya Janata Party’ (BJP), in power since 2014, increased its strength by 21 seats to 303 in the ‘Lok Sabha’, securing 38.55% of the votes cast. The number of seats won by its National Democratic Alliance (NDA) also rose to 350, but fell short of a two-thirds majority, and its percentage of votes increased to 45%. In monetary terms, the BJP received over 73% of the declared donations from India's largest political parties in 2017-2018 and over 94.5% of the electoral bonds, totaling at least £19 million. Overall, it is estimated that all political parties spent a total of over £6.7 billion, more than three times the cost of the United States presidential elections in 2016 (Roy-Chaudhury, 2019). Mistakes made by the principal opposition party, the Indian National Congress (INC), led to it winning only 52 seats out of 545, just eight more than in the 2014 elections. This was a result of differences among political leaders within the organization, a complacent approach to its program in the elections, betting on its voters repeating the trend of rejecting the incumbent government, and a refusal to accept pre-electoral alliances with regional parties in key States (Roy-Chaudhury, 2019).

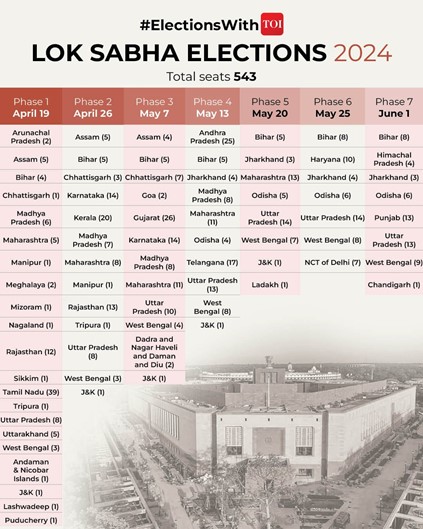

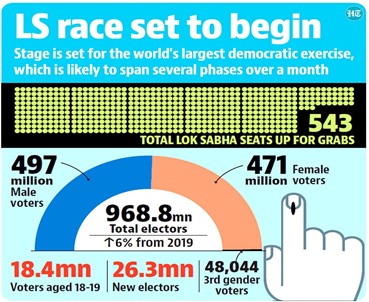

On March 16th, 2024, the Election Commission of India publicly announced the schedule for the ‘Lok Sabha’ elections to appoint the 543 seats. This schedule will be implemented nationwide in seven phases, from April 19th to June 1st, with the vote count taking place on June 4th, including assembly elections, by-polls, and general elections. The current government’s term ends on June 16th, 2024 (Hindustan Times, 2024a). Additionally, the data provided reveals that in this political process, the electoral roll amounts to a total of 968.8 million voters, of which 497 million are men and 471 million are women. It was also reported that 18.4 million voters fall in the age group of 18 to 19 years, 26.3 million are new voters, and 48,044 are senior citizens.

Source: The Times of India

Similarly, according to the mandate of the Supreme Court of India, data related to electoral bonds issued to each contesting party between April 12th, 2019, and January 11th, 2024, were published. The figures revealed that the largest recipient of donations was the BJP, and the largest national donor was the company Future Gaming and Hotel Services. This company accounted for bonds worth 1,365 million rupees distributed among several parties. The second-largest donor was Megha Engineering and Infrastructure Limited (MEIL) with 966 million rupees, of which 60.5% went to the BJP. In financial terms, the BJP received a total of 6,061 million rupees, with MEIL being its largest donor, followed by Qwik Supply Chain and Vedanta. For the INC, the largest donor was Vedanta with 125 million rupees, followed by Western UP Power Transmission Company Limited and MJK Enterprise, amounting to a total of 1,422 million rupees (Hindustan Times, 2024b). Currently, in India, there are two main coalitions competing in the 2024 general elections: the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) and the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), both of which include several parties. The NDA, led by the BJP, is a coalition of right-wing conservative parties formally established in 1998 to counter the then-dominant INC. Prominent parties in the alliance include the National People's Party (NPP), Shiv Sena, Janata Dal, Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD), Nationalist Congress Party (NCP), Janata Dal, Rashtriya Lok Janshakti Party (RLJP), and the currently dominant Bharatiya Janata Party since 2014. The candidate for prime minister is the current Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has stated the intention of securing over 400 seats for the NDA in these elections (Mint, 2024). The INDIA bloc was formed in 2023 by 26 opposition parties. It is currently led by the president of the INC, Mallikarjun Kharge, who is also the leader of the opposition in the Upper House of the Parliament. Other parties comprising the bloc include the All India Trinamool Congress (TMC), Aam Aadmi Party, Samajwadi Party, Shiv Sena (Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray), Communist Party of India (Marxist), and the Rashtriya Janata Dal (WION, 2024).

Source: Hindustan Times

On Friday, April 5th, the INC released its manifesto, this time focusing on equity, youth, women, farmers, workers, the Constitution, the economy, federalism, national security, and the environment. Its 2019 counterpart, mainly focused on the economy and livelihoods, also committing to cover government contracts and eliminate regulations to start a business. It also promised a budget for farmers and pledged to make the non-payment of agricultural loans a civil crime (Hindustan Times, 2024c). On the other hand, for the 2019 general elections, the BJP's electoral manifesto (Sankalp Patra) addressed issues related to nationalism, agriculture, infrastructure, governance, and zero tolerance towards terrorism. Similarly, commitments to amending the citizenship law to protect religious minorities from neighboring countries and the revocation of Article 370 of the Constitution addressing the autonomous status of Jammu and Kashmir and its change to a semi-autonomous position were fulfilled during the party's and Modi's mandate over the last 5 years. In the 2019 manifesto, the BJP also promised a pension scheme for all small and marginalized farmers in the country, a macroeconomic stability, as well as job generation and gender equality (Hindustan Times, 2024c)

The main surveys point to the BJP with Modi at the helm as the primary winning force in the elections. While the intention of both his party and the alliance he leads to conquer more than 400 seats is somewhat ambitious and hasn't been achieved since 1984 when the INC won 144 seats, the NDA is poised as the clear winner in these elections. On the other hand, India is divided by rivalries, political defections, and ideological clashes. "Analysts say that discussions about the allocation of seats within the alliance have cooled off, partly due to the demands of the Congress Party to field its own candidates in most seats, even in states where it is weak" (Agrawal and Anand, 2024). The truth is that the 2024 elections in India are shaping up as an exercise where the BJP and its coalition appear as clear winners. At the same time, it is very challenging for opposition leaders and parties to confront Modi, who after 10 years of national governance and 13 years of state administration, has demonstrated mostly successful implementation of his governance model. The INC and INDIA start from a very disadvantaged position when facing an overwhelming media machinery, a government that promotes laws to silence opposition, thus playing on favorable ground. Additionally, it's worth noting the growing popularity of the Prime Minister, who ranks as one of the most popular leaders worldwide with a 78% national approval rating. In a politically and religiously polarized India, where the government has been promoting an economic, social, and religious agenda aligned with the leading party for the past 10 years, and with a powerful technological and media mechanism, it is unthinkable to imagine that Modi will not secure his third consecutive term at the helm of the country.

Agrawal, Aditi y Anand, Utkarsh (2024). Electoral bonds: Donor-party link public after SC push. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/poll-bonds-donor-party-link-public-after-sc-push-101711046938707.html Mint (2024). BJP’s first list of candidates for Lok Sabha elections 2024 to be out today. https://www.livemint.com/politics/news/lok-sabha-elections-2024-bjp-first-list-to-be-out-today-11709377057949.html Rai, Indrajeet (2024). How BJP’s strenghts and weakness match up with Congress’s. Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/lok-sabha-elections-2024-pm-modi-rahul-gandhi-bjp-congress-how-bjps-strengths-and-weakness-match-up-with-congresss/articleshow/108614186.cms?utm_source=wa_channel&utm_medium=notification#google_vignette Times of India (2024b). Congress releases fourth list of 46 candidates for Lok Sabha polls. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/congress-releases-fourth-list-of-46-candidates-for-lok-sabha-polls/articleshow/108737876.cms?utm_source=wa_channel&utm_medium=notification Wion (2024). Lok Sabha Elections 2024: List of parties competing in the upcoming polls. https://www.wionews.com/india-news/lok-sabha-elections-2024-list-of-parties-competing-in-the-upcoming-polls-700851/amp Moreno Hernández, Dulce J. (2015). De Gujarat a India: Análisis de la trayectoria política y candidatura a Primer Ministro de Narendra Modi. Tesis de Maestría en Estudios de Asia y áfrica, Centro de Estudios de Asia y África, Colegio de México. https://repositorio.colmex.mx/concern/theses/wd375w520?f%5Bcenter_sim%5D%5B%5D=Centro+de+Estudios+de+Asia+y+%C3%81frica&f%5Bdirector_sim%5D%5B%5D=Banerjee-Dube%2C+Ishita&f%5Blanguage_sim%5D%5B%5D=espa%C3%B1ol&f%5Bmember_of_collections_ssim%5D%5B%5D=Producci%C3%B3n+Institucional&locale=en&per_page=100&view=list Stokes, Bruce (2014). Indians’ support for Modi, BJP shows an itch for change. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2014/02/27/indians-support-for-modi-bjp-shows-an-itch-for-change/ Molina Medina, Norbert y Duarte Peña, Juan J. (2015). Narendra Modi y la India de hoy (Primera Parte). Universidad de Los Andes, Centro de Estudios de África, Asia y Diásporas Latinoamericanas y Caribeñas “José Manuel Briceño Monzillo”. Muralidharan, Sukumar (2014). Modi, media and the feel-good effect. Himal Southasian. https://www.himalmag.com/comment/modi-media-and-the-feel-good-effect Roy-Chaudhury, Rahul (2019). Modi’s return as prime minister of ‘New India’. International Institute for Strategic Studies. https://www.iiss.org/en/online-analysis/online-analysis/2019/05/modi-return-new-india/ Hindustan Times (2024a). Lok Sabha Election 2024 Highlights: Polls begin on April 19, results on June 4; MCC kicks in. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/lok-sabha-election-2024-date-live-election-commission-esi-voting-result-date-time-schedule-announcement-today-march-16-101710550714891.html?utm_source=whatsapp&utm_medium=whatsappChannel Times of India (2024a). Lok Sabha elections: BJP releases fifth list of candidates, fields Kangana Ranaut, Naveen Jindal. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/lok-sabha-elections-bjp-releases-fifth-list-of-candidates-fields-kangana-ranaut-from-mandi/articleshow/108753780.cms?utm_source=wa_channel&utm_medium=notification Hindustan Times (2024b). BJP’s 5th candidates list for Lok Sabha election: Kangana Ranaut from Mandi, Arun Govil from Meerut. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/kangana-ranaut-bjps-candidate-from-mandi-arun-govil-from-meerut-101711294635407.html?utm_source=whatsapp&utm_medium=whatsappChannel Hindustan Times (2024c). In 2019, Congress’s manifesto primarily focused on economy, livelihoods. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/in-2019-congress-s-manifesto-primarily-focussed-on-economy-livelihoods-101712316094820.html

[1] An important feature of the process of electing the Prime Minister of India is that all candidates must be a member of the ‘Lok Sabha’ or ‘Rajya Sabha’, which means the candidate must contest elections to secure a seat representing a particular locality.First published in :

Graduate in International Relations from the Instituto Superior de Relaciones Internacionales “Raúl Roa García"

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!