The UN in crisis: Justice without power, power without justice

by Francisco Edinson Bolvaran Dalleto

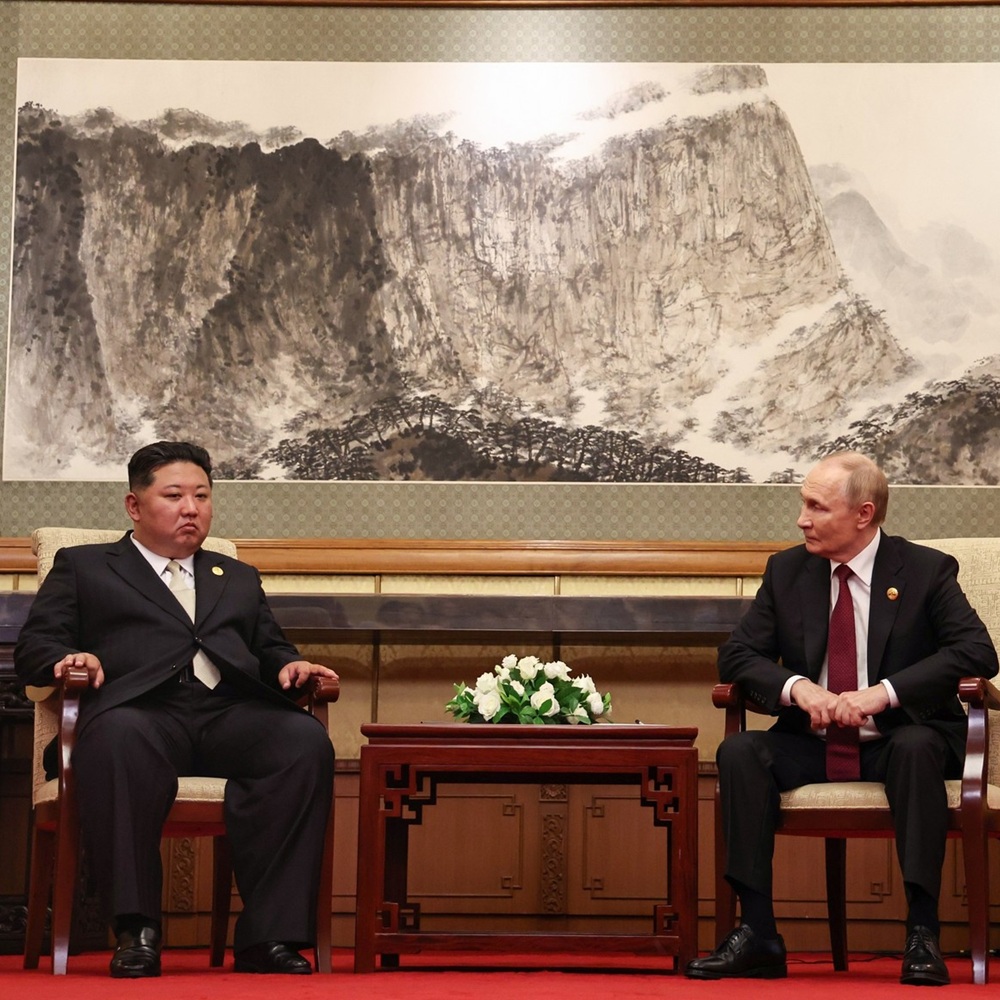

Abstract The United Nations (UN), eighty years after its creation, faces a structural crisis that reveals the tension between justice and power. This essay examines how the design of the Security Council, with its veto power, perpetuates an unequal order inherited from 1945 and limits the effectiveness of the collective security system. Through theoretical perspectives — Morgenthau, Schmitt, Habermas, Falk, and Strange — it is shown that international law remains subordinated to power interests, that proclaimed universality masks hegemonies, and that global economic dynamics lie beyond institutional reach. Cases such as Kosovo, Libya, Gaza, and Myanmar illustrate the paralysis and delegitimization of the Responsibility to Protect. Considering this scenario, two paths emerge: reforming multilateralism with limits on the veto and greater representativeness or resigning to a fragmented order. The conclusion is clear: without adaptation, the UN will become a symbolic forum, making chronic its inability to respond to current challenges. Dag Hammarskjöld, the second Secretary-General of the UN, warned: “The United Nations was not created to take us to heaven, but to save us from hell.” [1] Eighty years after its founding, that promise seems to falter in the face of multiple wars, such as those in Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, or Myanmar, among many others, with a sense of ineffectiveness, loss of prestige, and collective impotence being perceived: does the UN no longer fulfill the role it once assumed? At first glance, blame falls solely on the nature of the institution itself. But the root of the problem seems to lie not only in New York, but also in the main capitals of the world. The UN is nothing more than what States allow it to be. Its effectiveness depends on the will of those who comprise it; and the uncomfortable truth is that the great powers prefer to limit its scope rather than cede parcels of sovereignty. As John Rawls pointed out, a just international system requires that peoples accept common principles of justice. [2] Today, by contrast, it is a constant that collective interest systematically gives way to particular interest. The Security Council is the most evident symbol of this contradiction. It remains anchored in post-war logic, with five permanent members clinging to the privilege of the veto. That power, already met with skepticism in San Francisco in 1945, turned into a tool of paralysis. As Canada denounced in 2022, the veto is “as anachronistic as it is undemocratic” and has prevented responses to atrocities. [3] Aristotle said that “justice is equality, but only for equals.” [4] In the UN, the Assembly proclaims sovereign equality, while the Council denies it in practice: some States remain “more equal” than others. The UN Charter articulates its backbone in a few luminous rules: the prohibition of the use of force (Art. 2.4), non-intervention in internal affairs (Art. 2.7), and, as a counterbalance, the collective security system of Chapter VII (Arts. 39–42), which grants the Security Council the authority to determine threats to peace and authorize coercive measures. In parallel, Art. 51 preserves the right of self-defense against an “armed attack.” [5] This normative triangle — prohibition, collective security, defense — is the promise of a world governed by law and not by force, but it must be put into practice. In the 1990s, a dilemma arose: what to do when a State massacres its own population or is unable to prevent it? The political-legal response was the Responsibility to Protect (R2P), affirmed at the 2005 World Summit (paras. 138–139). [6] Its architecture is sequential: (I) each State has the primary responsibility to protect its population against genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity; (II) the international community must help States fulfill that responsibility; and (III) if a State manifestly fails, the international community, through the Security Council, may adopt collective measures — preferably peaceful ones; as a last resort, coercive — case by case and in accordance with the Charter. Properly understood, R2P is not a license to intervene; it is a duty to protect framed within International Law. The historical record shows both its necessity and its perverse effects. Kosovo (1999) inaugurated, without authorization from the Council, the narrative of “humanitarian intervention,” based on a supposed “legitimate illegality.” [7] The precedent left a dangerous standard: humanitarian purposes invoked to circumvent the hard core of the Charter. Libya (2011) seemed to be the “ideal case” of R2P: the Council authorized “all necessary measures” to protect civilians. [8] However, the shift toward regime change eroded the trust of Russia and China, which since then have blocked robust resolutions on Syria, hollowing out the effectiveness of R2P. [9] The lesson is bitter: when protection is perceived as a vehicle of hegemony, the norm is delegitimized, and the veto becomes reflexive. Gaza and Myanmar display the other face of paralysis. In Gaza, the Council’s inability to impose sustainable ceasefires — despite patterns of hostilities that massively impact the civilian population — has shifted the debate to the General Assembly and the International Court of Justice through interstate actions and provisional measures. [10] In Myanmar, the genocide of the Rohingya mobilized condemnations, sanctions, and proceedings before the International Court of Justice (hereinafter, ICJ), [11] but did not trigger a coercive response from the Council. R2P exists on paper; its implementation is captive to the veto. Thus, the “right to have rights” that Arendt spoke of still depends on geopolitics. [12] History teaches that international law has always been strained by force. Rousseau warned that the strong seek to transform their power into law. [13] That is what the winners of 1945 did by crystallizing their hegemony in the Charter. And so, what Kant dreamed of as perpetual peace remains chained to an unequal order. [14] The UN, more than a republic of law, still seems a field of power. That fragility has opened space for alternatives. The BRICS, for example, have emerged as a heterogeneous bloc that combines the cohesion of historically homogeneous powers such as China and Russia with the diversity of India, Brazil, and South Africa. Paradoxically, their strength lies in articulating that heterogeneity against a common enemy: the concentration of power in the Security Council. [15] In a multipolar world, heterogeneity ceases to be a weakness and becomes a driver of plurality and resistance. The UN crisis is not only about security; it is also economic and distributive. The universalist promise of the Charter (Arts. 1.3 and 55–56, on cooperation for development) coexists with a global financial architecture whose heart beats outside the UN: the IMF and World Bank, designed in Bretton Woods, project a structural power — in Susan Strange’s terms — that conditions public policies, access to liquidity, and investment capacity. [16] The sovereign equality proclaimed in New York becomes blurred when the asymmetry of weighted voting in financial institutions (and the conditionality of credit) makes some States more “equal” than others. This is not a recent claim. Since the 1960s, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and, later, the Declaration on a New International Economic Order (1974), sought to correct structural problems such as the deterioration of terms of trade and the dependence between “center” and “periphery” countries, as Prebisch had pointed out. [17] However, the results were limited: ECOSOC lacks teeth, UNDP mobilizes cooperation but fails to change the rules of the system, and the 2030 Agenda sets important goals but without mandatory enforcement mechanisms. [18] The pandemic and the climate crisis have further worsened these inequalities, highlighting problems such as over-indebtedness, the insufficiency in the reallocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), and climate financing that often arrives late and under unsuitable conditions. In this scenario, the New Development Bank of the BRICS emerges, seeking to open a path toward greater financial autonomy for developing countries. [19] International economic justice is the reverse side of collective security. Without fiscal space or technological transfer, the Global South remains trapped between development promises and adjustment demands. The UN has political legitimacy to outline a Global Economic Council (as proposed by the Stiglitz Commission in 2009) [20] to coordinate debt, international taxation, and global public goods, but it currently lacks normative muscle. The result is fragmentation: fiscal minilateralism, climate clubs, and value chains that distribute risks to the South and rents to the North. The solution does not lie simply in “more aid,” but in prudent rules such as: (I) a multilateral debt restructuring mechanism under UN auspices; [21] (II) effective international taxation on intangibles and the digital economy; [22] (III) binding compliance with the loss and damage fund in climate matters; [23] and (IV) a reform of quotas in IFIs that reflects the real weight of emerging economies. [24] Without constitutionalizing — even gradually — this economic agenda, sovereign equality will remain an empty liturgy and the discontent of the Global South a political fuel that erodes the UN from within. The truth is that the United Nations of 1945 no longer responds to the challenges of 2025. As the president of Brazil recently said: “The UN of 1945 is worth nothing in 2023.” [25] If States do not recover the founding spirit — placing collective interest above particular ones — the organization will remain prisoner of the veto and the will of a few. The question, then, is not whether the UN works, but whether States really want it to work. Taking the above into account, this essay will analyze the UN crisis from three complementary dimensions. First, the theoretical and philosophical framework that allows us to understand the tension between power and law will be addressed, showing how different authors highlight the structural roots of this contradiction. Second, historical episodes and current examples will be reviewed to illustrate the paralysis and democratic deficit of the organization. Finally, possible scenarios for the future will be projected, engaging in the exercise of evaluating the minimum reforms that could revitalize multilateralism in contrast to the alternative of critical global fragmentation. Considering all together, the argument is that the UN finds itself trapped between justice without power and power without justice, and that its survival depends on its ability to adapt to an international order radically different from that of 1945. I. The contradiction between power and law: Hans Morgenthau and political realism To understand the paralysis of the UN, it is useful to turn to Hans Morgenthau, a pioneer of realism in international relations. In his work “Politics Among Nations” (1948), he warned that the international order is always mediated by the balance of power and that legal norms only survive to the extent that they coincide with the interests of powerful States. [26] His idea is provocative: international law is not an autonomous order, but a language that powers use so long as it does not contradict their strategic objectives. Applied to the UN, this analysis is clear: the institution reflects less universal ethical commitment and more correlation of historical forces. The Security Council is not a neutral body, but the mirror of the hegemony of 1945, crystallized in Article 27 of the Charter, which enshrines the right of veto. The supposed universality of the UN is subordinated to a mechanism designed precisely to ensure that no action contrary to the superpowers could be imposed. Contemporary critiques confirm Morgenthau’s intuition. When Russia vetoes resolutions on Ukraine, [27] or the United States does the same regarding Gaza, [28] it becomes evident that international justice is suspended in the name of geopolitics. The legal is subordinated to the political. In this sense, the UN crisis is not an accident, but the logical consequence of its design, and what Morgenthau pointed out seventy years ago remains valid: as long as there is no coincidence between law and power, international norms will remain fragile. Political realism helps explain why the UN fails when it is most needed. States continue to act according to their national interests, even when this contradicts the international norms they themselves have subscribed to. The Security Council has become a space where powers project their strategies of influence, blocking collective actions whenever these affect their geopolitical priorities. The war in Ukraine, the invasion of Iraq in 2003, and the inaction in the face of the Rwandan genocide show that international law is applied selectively, reinforcing the idea that rules are valid only when they do not interfere with the power of the strongest. This pattern evidently erodes the legitimacy of the UN in the eyes of societies, because it generates the perception that the organization is incapable of representing the collective interest and, instead, merely reflects the correlation of forces of each historical moment. II. Carl Schmitt and the Myth of Universal Order Another voice that resonates is that of Carl Schmitt, who in “The Nomos of the Earth” (1950) argued that every international legal order arises from a founding political decision, that is, an act of power. [29] For Schmitt, there is no “universal law” that imposes itself; what is presented as universal is, in reality, the crystallization of a particular domain. The UN perfectly embodies this diagnosis. The founding discourse of San Francisco in 1945 spoke of “we the peoples of the United Nations,” [30] but in reality the Charter was written under the predominance of the winners of the Second World War. What was presented as a universal order of peace and security was, in fact, the codification of the Allied hegemony. Schmitt helps explain why the UN has never escaped that original logic. Although the General Assembly proclaims sovereign equality in Article 2 of the Charter, the structure of the Council reproduces the privilege of a few. [31] The international law of the UN appears, in Schmittian terms, as a “nomos” imposed by the winners, not as a true universal community. The consequence is a legitimate deficit that has persisted until today and explains much of the perception of ineffectiveness. The original structure of the UN perpetuates an unequal design that remains in force. The veto privilege is not only a defensive mechanism for the winners of the Second World War, but it has also functioned as a lock — one without keys — that prevents any real evolution of the system. Over eight decades, demands for reform have clashed with the resistance of those who benefit from keeping the rules intact. The contradiction is evident: developing States, which today represent the majority in the General Assembly, lack effective power in the most important decisions on international security. The gap between the universalist discourse of sovereign equality and the hierarchical practice of the Council undermines the credibility of the multilateral order. As long as this tension persists, the UN will hardly be able to become the space of global governance that the world requires more urgently than ever in the 21st century. III. Habermas and the Need for a Deliberative Community In contrast to this pessimism, Jürgen Habermas offers a different perspective. In “The Inclusion of the Other” (1996) and in later essays, he proposed moving toward a “constitutionalization of international law,” understood as the creation of a global normative space in which decisions are not based on force, but on rational deliberation. [32] From this perspective, the UN would be an imperfect embryo of a community of world citizens. The impact of this idea is enormous: it suggests that, beyond current deadlocks, the UN embodies the possibility of transforming power relations into processes of public deliberation. Article 1 of the Charter, which speaks of “maintaining international peace and security” and of “promoting friendly relations among nations,” can be read not only as a political mandate but also as a normative ideal of cosmopolitan coexistence. [33] Criticism of Habermas is evident: his proposal errs on the side of idealism in a world where national security interests remain paramount. However, his contribution is valuable because it allows us to think of the UN not only as a paralyzed body but also as a field of normative struggle. The problem is not only the strength of the vetoes but also the lack of will to transform that space into a true deliberative forum. [34] Thinking of the UN as a deliberative community requires recognizing that its current procedures do not guarantee authentic dialogue. Debate in the General Assembly is often reduced to formal statements, while crucial decisions, as everyone knows, are taken in restricted circles. The lack of effective mechanisms for the participation of non-state actors, such as regional organizations or civil society, further limits the inclusive character of the institution. Genuine deliberation should open spaces where multiple voices can influence decision-making processes, not only through speeches but by building binding consensus. However, the most powerful States fear losing control over the international agenda, which generates a vicious circle: an elitist governance system is maintained that protects privileges, but at the cost of sacrificing legitimacy and effectiveness. Thus, the promise of a deliberative order is reduced to a normative horizon that has not yet been realized. IV. Richard Falk and the Global Democratic Deficit A more recent contribution comes from Richard Falk, jurist and former UN rapporteur, who has insisted on the “democratic deficit” of the international order. In his view, the UN suffers from a structural contradiction: while the Charter proclaims the sovereignty of peoples, in practice it concentrates power in a small club of States. [35] This not only limits its effectiveness but also erodes its legitimacy in the eyes of the peoples of the world. The case of Palestine is emblematic. The General Assembly has repeatedly recognized the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination, but the veto in the Council blocks any effective measure. [36] Falk interprets this as evidence that the UN operates under a “democracy of States” but not under a “democracy of peoples.” The impact is devastating: millions of people perceive the organization not as a guarantor of rights, but as an accomplice to inequality. This leads us to a brief analysis of the International Criminal Court (ICC), born from the Rome Statute (1998), which promised a civilizational breakthrough: that the most serious crimes (“which affect the international community as a whole”) would not go unpunished. [37] Its design is cautious: complementarity (it acts only if the State is unwilling or unable), restricted jurisdiction (genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and — with limits — aggression), and jurisdiction based on territory, nationality, or referral by the Security Council. The two major milestones of the Council — referrals of Darfur (2005) and Libya (2011) —demonstrated both the potential and the limits. There were procedural advances and arrest warrants, but also contested operative clauses and very little cooperation for arrests. [38] The implicit message to the Global South was ambiguous: justice is universal, but its activation depends on the map of alliances in the Council. At the same time, key powers are not parties to the Statute (United States, China, Russia) and yet influence when the Court acts. The result fuels the argument of “winners’ justice” that several African foreign ministries have raised. The Court has tried to rebalance its map: investigations in Afghanistan, Palestine, and Ukraine, as well as arrest warrants against high-ranking authorities in cases of aggression or serious international crimes, have partly disproved the idea of a one-sided persecution. But the Achilles’ heel persists: without State cooperation, there are no executions of warrants; without the Council, there is no activation in key contexts; with the Council, there is a veto. In addition, Article 16 of the Statute allows the Council to suspend investigations for 12 renewable months, a political valve that subordinates the judicial to the geopolitical. [39] Integrating Falk’s critique into this essay makes it possible to highlight that the UN crisis is not only institutional but also democratic. Article 1.2 of the Charter proclaims respect for the principle of equal rights and the self-determination of peoples, but this ideal becomes empty when the veto power systematically contradicts it. [40] The democratic deficit of the UN is not limited to the Security Council but runs through the entirety of its institutional architecture. Developing countries have little influence on global economic governance, despite being the most affected by decisions on debt, trade, or climate financing. Unequal representation in bodies such as the IMF and the World Bank, together with dependence on international cooperation, reproduces relations of subordination that contradict the principles of equality and self-determination. Moreover, world citizenship lacks a real channel of influence: peoples see their demands diluted in state structures that do not always — or almost never — reflect their needs. This divorce between peoples and States turns the UN into an incomplete democracy, where the most vulnerable collective subjects fail to make their voices heard. Overcoming this limitation is essential to restoring the legitimacy of multilateralism. V. Susan Strange and the Geopolitics of the Economy Finally, Susan Strange adds another dimension: the economic one. In “The Retreat of the State” (1996), she argued that power in the contemporary world does not reside only in States, but also in transnational forces — financial markets, corporations, technologies — that escape institutional control. [41] The UN, designed in 1945 under the logic of sovereign States, lacks instruments to govern this new scenario. The impact is evident. While the Security Council is paralyzed in debates over traditional wars, global crises such as climate change, pandemics, or the regulation of artificial intelligence show that real power has shifted toward non-state actors. [42] Strange warns that if international institutions do not adapt to this reality, they risk becoming irrelevant. In this sense, the UN faces not only a problem of veto or representativeness, but also a historical mismatch: it was designed for a world of States and conventional wars, but today we live in a world of transnational interdependencies. The Charter, in its Article 2.7, continues to emphasize non-interference in the internal affairs of States, but this clause seems insufficient to govern global threats that transcend borders. [43] And it is vitally important to note that the global threats of the 21st century do not fit the traditional paradigm of interstate wars that has been preconceived. Challenges such as climate change, pandemics, and technological revolutions pose risks that no State can face alone. However, the UN lacks effective mechanisms to coordinate global responses in these areas. The fragmentation of climate governance, competition for vaccines during the pandemic, and the absence of clear rules to regulate large digital corporations illustrate the magnitude of the challenge. In this context, state sovereignty proves insufficient, and the principle of non-interference becomes obsolete. If the UN does not develop innovative instruments that integrate transnational actors and strengthen multilateral cooperation, it risks becoming a merely declarative forum, incapable of offering concrete solutions to the problems that most affect contemporary humanity — and it is important that these critiques be heard before it is too late. VI. Current Scenarios All the above opens up a momentous dilemma of our time: either we reform multilateralism so that law contains “force,” or we normalize “exception” forever. [44]Scenario A: A minimal but sufficient cosmopolitan reform. A critical group of States —supported by civil society and epistemic communities — agrees to self-limit the veto in situations of mass atrocities (ACT-type codes of conduct), promotes the expansion of the Council with some permanent presence of the Global South (India, Brazil, Germany, Japan, and one African seat, probably South Africa), and strengthens “Uniting for Peace” mechanisms to circumvent blockages. [45] The ICJ gains centrality with advisory opinions politically bound by prior compliance commitments, the ICC ensures interstate cooperation through regional agreements, and the UN creates a rapid civil deployment capacity for the protection of civilians, minimal cybersecurity, and climate response. [46] In the economic sphere, a Global Economic Council emerges within the orbit of the UN to coordinate debt, climate, and international taxation with common standards. [47] Scenario B: Ordered fragmentation of anarchy. Blockages become chronic. Security shifts to ad hoc coalitions and minilateralisms (NATO Plus, QUAD, expanded BRICS), economic governance is decided in restricted membership forums, and the UN remains a symbolic forum without decision-making capacity. [48] Exception becomes the rule: “preventive interventions,” widespread unilateral sanctions, proliferation of private military companies, opaque cyber-operations, and a data ecology controlled by a few platforms. [49] International law endures as a language, but its social force dissipates; incentives push toward strategic autonomy and legal security by blocs. In other words, the future of the UN will depend on its ability to balance justice and force in an international environment marked by multipolarity. I insist that one possible path is to advance toward gradual reforms that strengthen transparency, broaden the representativeness of the Council, and grant greater autonomy to the General Assembly and judicial bodies. Another, far more radical, is the consolidation of parallel mechanisms that de facto replace the role of the UN through regional alliances, ad hoc coalitions, and alternative economic forums. Both paths involve risks: reform may stagnate in the lowest common denominator, while fragmentation may deepen inequalities and conflicts. However, what seems clear is that maintaining the status quo will only prolong paralysis and further weaken the legitimacy of the multilateral system. The choice between reform or irrelevance will, ultimately, be the decisive dilemma of the 21st century. I believe that three milestones will indicate where we are headed: (1) effective adoption of commitments to abstain from vetoes in the face of mass atrocities; (2) funded and operational implementation of the climate loss and damage mechanism; (3) cooperation with the ICC in politically sensitive cases, without ad hoc exceptions. [50] VII. Conclusion: Between Disillusionment and Hope The UN marks eighty years caught in Pascal’s dilemma: “force without justice is tyranny, justice without force is mockery.” [51] The diagnosis is clear: the Security Council has turned justice into a mockery, while the great powers have exercised force without legitimacy. [52] The result is a weakened organization, incapable of responding to the most urgent tragedies of our time. However, it would be a mistake to fall into absolute cynicism. Despite its evident limitations and alongside all that has been mentioned, the UN remains the only forum where 193 States engage in dialogue, the only space where there exists even a minimal notion of common international law. [53] Its crisis should not lead us to abandon it, but rather to radically rethink it. Perhaps the path lies in what Habermas calls a “constitutionalization of international law,” as previously proposed, or in a profound reform of the Security Council that democratizes the use of force. [54] History teaches that institutions survive if they manage to adapt. [55] If the UN does not, it will be relegated to the status of a giant that humanity needs but that is paralyzed, a symbol of a past that no longer responds to the challenges of the present. [56] But if States recover something of the founding spirit of 1945, perhaps it can still save us from hell, even if it never takes us to heaven. [57] VIII. References [1] Dag Hammarskjöld. Hammarskjöld. Citado en Brian Urquhart. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972.[2] John Rawls. The Law of Peoples. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.[3] Permanent Mission of Canada to the United Nations. Statement on the Veto. UN General Assembly, 26 April 2022.[4] Aristóteles. Política. Traducido por Antonio Gómez Robledo. México: UNAM, 2000.[5] Naciones Unidas. Carta de las Naciones Unidas. San Francisco: Naciones Unidas, 26 de junio de 1945.[6] Naciones Unidas. World Summit Outcome Document. A/RES/60/1, 24 October 2005.[7] Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The Social Contract. New York: Penguin, 1968.[8] Immanuel Kant. Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. 1795; repr., Indianapolis: Hackett, 2003.[9] Oliver Stuenkel. The BRICS and the Future of Global Order. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015.[10] Susan Strange. States and Markets. London: Pinter, 1988. 11. Hedley Bull. The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics. New York: Columbia University Press, 1977.[12] Kenneth Waltz. Theory of International Politics. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1979.[13] Martha Finnemore. National Interests in International Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996.[14] Alexander Wendt. Social Theory of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.[15] Francis Fukuyama. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press, 1992.[16] Samuel Huntington. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.[17] Joseph Nye. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. New York: Public Affairs, 2004.[18] Joseph Nye. The Future of Power. New York: Public Affairs, 2011.[19] Robert Keohane y Joseph Nye. Power and Interdependence. Boston: Little, Brown, 1977.[20] Robert Keohane. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.[21] Stephen Krasner. Structural Conflict: The Third World Against Global Liberalism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985.[22] Robert Cox. “Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory.” Millennium: Journal of International Studies 10, no. 2 (1981): 126–55.[23] Robert Cox. Production, Power, and World Order: Social Forces in the Making of History. New York: Columbia University Press, 1987.[24] Charles Kindleberger. The World in Depression, 1929–1939. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.[25] John Ikenberry. After Victory: Institutions, Strategic Restraint, and the Rebuilding of Order after Major Wars. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001.[26] John Ikenberry. Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.[27] Paul Kennedy. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Random House, 1987.[28] Michael Doyle. Ways of War and Peace: Realism, Liberalism, and Socialism. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997.[29] Charles Beitz. Political Theory and International Relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.[30] Andrew Moravcsik. “Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics.” International Organization 51, no. 4 (1997): 513–53[31] Peter Katzenstein, ed. The Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.[32] Friedrich Kratochwil. Rules, Norms, and Decisions: On the Conditions of Practical and Legal Reasoning in International Relations and Domestic Affairs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.[33] Nicholas Onuf. World of Our Making: Rules and Rule in Social Theory and International Relations. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1989.[34] Christian Reus-Smit. The Moral Purpose of the State: Culture, Social Identity, and Institutional Rationality in International Relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999.[35] Martha Finnemore y Kathryn Sikkink. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change.” International Organization 52, no. 4 (1998): 887–917.[36] Michael Barnett y Martha Finnemore. Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.[37] Ian Hurd. After Anarchy: Legitimacy and Power in the United Nations Security Council. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.[38] Allen Buchanan y Robert Keohane. “The Legitimacy of Global Governance Institutions.” Ethics & International Affairs 20, no. 4 (2006): 405–37.[39] Thomas Franck. The Power of Legitimacy among Nations. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.[40] David Held. Democracy and the Global Order: From the Modern State to Cosmopolitan Governance. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995.[41] Ian Hurd. After Anarchy: Legitimacy and Power in the United Nations Security Council. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.[42] Permanent Mission of Canada to the United Nations. Statement on the Veto. UN General Assembly, 26 April 2022.[43] Oliver Stuenkel. The BRICS and the Future of Global Order. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2015.[44] Naciones Unidas. World Summit Outcome Document. A/RES/60/1, 24 October 2005.[45] Corte Internacional de Justicia. Advisory Opinions. La Haya: CIJ, varios años.[46] Naciones Unidas. Report of the High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change. A/59/565, 2 December 2004.[47] Samuel Huntington. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.[48] Robert Keohane. After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.[49] Thomas Franck. The Power of Legitimacy among Nations. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.[50] Joseph Nye. The Future of Power. New York: Public Affairs, 2011.[51] Blaise Pascal. Pensées. París: Éditions Garnier, 1976.[52] Brian Urquhart. Hammarskjöld. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972.[53] Naciones Unidas. Charter of the United Nations. San Francisco: Naciones Unidas, 1945.[54] Jürgen Habermas. The Postnational Constellation: Political Essays. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001.[55] John Ikenberry. Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.[56] Paul Kennedy. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Random House, 1987.[57] David Held. Democracy and the Global Order: From the Modern State to Cosmopolitan Governance. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995.