Press conference by Federal Chancellor Scholz and the Prime Minister of Malaysia, Anwar Ibrahim, on Monday, March 11, 2024 in Berlin - Wording

by Olaf Scholz , Anwar Ibrahim

BK Scholz: A warm welcome, Mr. Prime Minister! I am delighted to welcome you here to Germany for the first time. Your visit is a very special start to a Southeast Asia Week with several high-ranking visits from this important region of the world here in Berlin.

The Indo-Pacific region is of great importance to Germany and the European Union. We therefore want to intensify political and economic cooperation. Germany already maintains close economic relations with the region. Malaysia is Germany's most important trading partner in ASEAN. This is of great importance because it is associated with many direct investments in the country, but also with all the economic exchange that results from this.

We would like to further expand this partnership. Of course, this is particularly true with regard to the objective of further diversifying our economic relations with the whole world. We want to have good economic and political relations with many countries.

We also want closer cooperation on climate protection and the expansion of renewable energies. We are therefore very pleased with Malaysia's announcement that it will stop building new coal-fired power plants and dramatically increase the share of renewable energies. We think this is very important.

Malaysia and Germany are established democracies. We are both committed to multilateralism and compliance with international law. It is therefore also right that we deepen our security and defense cooperation. The defense ministries are already working on the necessary cooperation agreements.

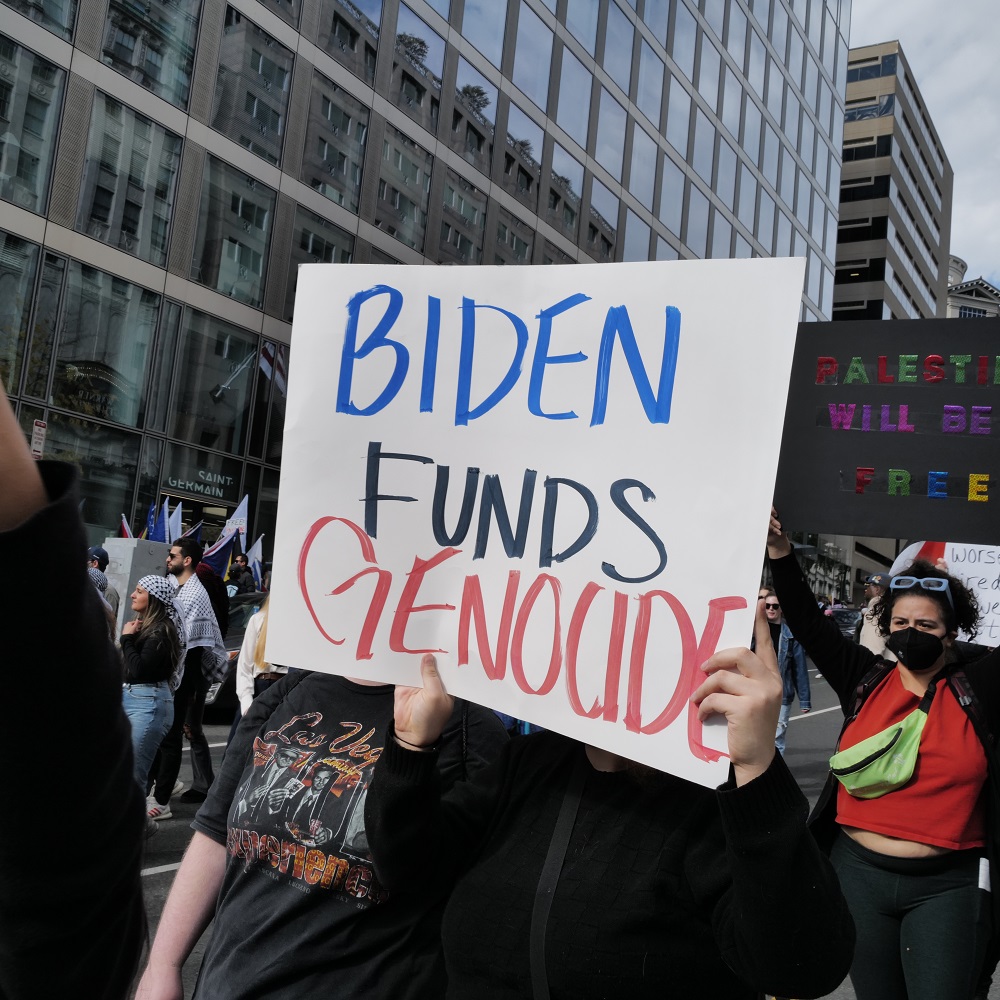

Of course, we also discussed developments in the Middle East, developments in Gaza and the situation following the Hamas attack on Israeli citizens. It is no secret that our perspective on the Middle East conflict is different to that of others. But that makes it all the more important to exchange views with each other. In any case, we agree that more humanitarian aid must reach Gaza. This is also our clear call to Israel, which has every right to defend itself against Hamas. We do not believe that a ground offensive on Rafah is right.

An important step now would also be a ceasefire that lasts longer, preferably during Ramadan, which has now begun and during which we broke the fast together today. Such a ceasefire should help to ensure that the Israeli hostages are released and that, as I said, more humanitarian aid arrives in Gaza.

We also have a very clear position on long-term development. Only a two-state solution can bring lasting peace, security and dignity for Israelis and Palestinians. That is why it is so important that we all work together to ensure that a good, peaceful perspective, a lasting common future is possible for Israelis and Palestinians, who coexist well in the two states.

Of course, the world is marked by many other conflicts and wars, especially the dramatic war that Russia has started against Ukraine. It is a terrible war with unbelievable casualties. Russia, too, has already sacrificed many, many lives for the Russian president's imperialist mania for conquest. This is against all human reason. That is why we both condemn the Russian war of aggression. It is important to emphasize this once again.

The Indo-Pacific is of great importance for the future development of the world. Of course, this also applies to all the economic development and development of the countries there. I therefore welcome the efforts of Malaysia and the ASEAN states to settle disputes peacefully and to find ways to ensure that this becomes typical of everything that has to be decided there. Any escalation must be avoided at all costs. Peace and stability must always and everywhere be maintained on the basis of international law. This applies in particular to the freedom of the sea routes and compliance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. That is why the ongoing negotiations on the Code of Conduct are so important.

Thank you once again for coming to Berlin on the first day of Ramadan, at least for our location. We broke the fast together earlier. For me, this is a good sign of peaceful coexistence and solidarity. I see it as something very special. Ramadan Kareem!

PM Anwar: Thank you very much, Mr. Chancellor, dear Olaf! Thank you for your wonderful hospitality and for bringing us together today to break the fast!

Germany is of course one of our most important partners in Europe. We have seen a huge increase in trade and investment. We can see that major investments have been made. We have visited Siemens. Infineon is a big investor in Malaysia and is showing its confidence in the country and the system here. There are many other examples of companies operating in Malaysia. Of course, my aim is always to expand bilateral relations in the areas of trade and investment and also to benefit from your experience, both in the field of technology and in environmental and climate protection issues.

We have set ourselves clear goals for the energy transition. We have drawn up an action plan that is also in line with your policy. Renewable energy, ammonia, green hydrogen - we are pursuing these very actively. Fortunately, Malaysia is also a hub within ASEAN for these renewable energies and technologies. We welcome the German interest in this, also with regard to new investments in the renewable energy sector and with a view to climate change. We have of course discussed this cooperation on this occasion and I am pleased with the Chancellor's willingness to tackle many of these issues. Sometimes we have small differences of view, but it really shows the trust we have in each other.

As far as the war in Gaza is concerned, we agree that the fighting must stop. We need a ceasefire immediately. We also need humanitarian aid for the people of Palestine, especially in Gaza. Of course we recognize the concern about the events of 7 October. We also call on Europeans, and Germany in particular, to recognize that there have been 40 years of atrocities, looting, dispossession of Palestinians.

Let us now look forward together! I agree with the Chancellor on what he said about the two-state solution. It will ensure peace for both countries. Together we can ensure that there is economic cooperation and progress for the people in the region.

We have also positioned ourselves with regard to the war in Ukraine. We have taken a very clear stance against aggression, against efforts to conquer. This applies to every country and, of course, also to Russian aggression in Ukraine. We want a peaceful solution to the conflict. Because this conflict has an impact on trade and economic development as far away as Asia.

We have a peaceful region. ASEAN is currently the fastest growing economic area in the world, precisely because it is so peaceful - apart from the issue in Myanmar, but that is contained within Myanmar. The conflict has not spread to the region, although there are of course refugee movements. Within ASEAN, we have jointly agreed on a five-point consensus and the parameters by which the issue can be resolved. The ASEAN countries have agreed that Laos, Malaysia and Indonesia would like to lead the troika together and resolve the conflict with Myanmar.

Then there are other issues such as the South China Sea and China. I assured the Chancellor that we are getting along well with China. We have not seen any difficult incidents, but of course we see ourselves as an absolutely independent country. We are of course a small country, but we stand up for our right to cooperate with many countries to ensure that the people of Malaysia also benefit from these mechanisms and from cooperation with other countries.

Once again, Mr. Chancellor, thank you very much for this meeting. I am very impressed by your insight, by your analysis of the situation. It is very impressive to see what a big country like Germany is doing, and it was also good to share some of our concerns. I am pleased with the good cooperation. It's not just about trade and investment, it's also about the overall development of bilateral relations in all areas. I also told the Chancellor that the study of Goethe is gaining interest in Malaysia. Questions from JournalistsQuestion: Mr. Prime Minister, can you tell us something about the progress of German investment in Malaysia and can you say something about the challenges for the government in the transition to renewable energy in Malaysia?

Mr. Chancellor, in 2022 you spoke about the turning point in German foreign and security policy. But if you now look at ASEAN or Southeast Asia: How does Germany see Malaysia in terms of its bilateral importance, trade and also regional issues?

PM Anwar: Within the European Union, Germany is our biggest trading partner. They have made large investments, up to 50 billion US dollars. I have already addressed Infineon and many other leading German companies and I have said in our discussions that we are very pleased that they have chosen Malaysia as an important hub, as a center of excellence, as a training center in the region and I look forward to further cooperation in this area.

Of course, I also mentioned that education should be a priority. There are 1000 Malaysian students here in Germany and also several hundred German students in Malaysia. We are also very happy about that. We are working with many German companies to train people and strengthen cooperation.

We have taken important steps in renewable energy. We are investing in solar energy, in green energy and in our renewable energy export capacity. There is now an undersea green energy cable to the new capital of Indonesia, another to Singapore, and another cable to the Malay Peninsula. You can also see from the fact that data centers and artificial intelligence are growing and thriving in the Malaysian region that this has great potential.

BK Scholz: Thank you very much for the question. - First of all, the turning point lies in the Russian attack on Ukraine. This was the denunciation of an understanding that we have reached in the United Nations, in the whole world, namely that no borders are moved by force. But the Russian war of aggression is aimed at precisely that, namely to expand its own territory as a large country at the expense of its neighbor - with a terrible war. We cannot accept this - not in Europe and not anywhere else in the world. That is why it is right for us to support Ukraine and to do so in a very comprehensive manner. After the USA, Germany is the biggest supporter - both financially and in terms of arms supplies - and in Europe it is by far the country that is making the greatest efforts to help Ukraine defend itself.

But this touches on an issue that is important for the whole world. Anyone who knows a little about the history of the world - and it is colorful and diverse - knows that if some political leader is sitting somewhere, leafing through history books and thinking about where borders used to be, then there will be war all over the world for many, many years. We must therefore return to the principle of accepting the borders as they are and not changing them by force. That is the basis for peace and security in the world. That is why we are also very clear on this together.

For Germany, however, this does not mean that we lose sight of our own economic development, the development of Europe and the world. As you may already have noticed, it is particularly important for the government I lead and for me as Chancellor of Germany that we now make a major new attempt to rebuild relations between North and South and to ensure that we cooperate with each other on an equal footing in political terms, that we work together on the future of the world, but that we also do everything we can to ensure that the economic growth opportunities and potential of many regions in the world are exploited to the maximum.

This is why economic cooperation between Europe and ASEAN, between Germany and ASEAN, between Germany and Malaysia plays such an important role, and we want to make progress in the areas we have just mentioned. Renewable energies are central to this. We know that: We need to increase the prosperity of people around the world. Billions of people want to enjoy a level of prosperity similar to that which has been possible for many in the countries of the North in recent years. If this is to succeed, it will only be possible if we do not damage the environment in the process, which is why the expansion of renewable energies is so important.

New and interesting economic opportunities are also emerging, for example in the area of hydrogen/ammonia - this has been mentioned - because the industrial perspective of the future will depend on more electricity, which we need for economic processes - and this from renewable energies - and on hydrogen as a substitute for many processes for which we currently use gas, coal or oil. Driving this forward and creating prosperity together all over the world is a good thing.

The fact that the German semiconductor industry and successful German companies in the electronics sector are investing so much in Malaysia is a good sign for our cooperation. We want to intensify this.

Question: Thank you very much, Mr. Prime Minister. Your government supports Hamas and, unlike Western countries, has not described Hamas' attack on Israel as terrorism. In November you said that Hamas was not a terrorist organization. Do you stand by this assessment and are you not afraid that this position on Hamas could affect relations with countries like Germany?

Mr. Chancellor, I have a question for you: Do you think that Malaysia's position on Hamas could damage bilateral relations between Germany and Malaysia?

And if I may, one more question on Ukraine: Germany is still discussing the delivery of cruise missiles to Ukraine. The Foreign Minister said yesterday that a ring swap with the UK was an option, i.e. Germany sending Taurus cruise missiles to the UK and the UK then sending its Storm Shadow cruise missiles to Ukraine. Do you think this is also an option?

PM Anwar: Our foreign policy position is very clear and has not changed. We are against colonialism, apartheid, ethnic cleansing and dispossession, no matter in which country it takes place, in Ukraine or in Gaza. We cannot simply erase or forget 40 years of atrocities and dispossession that have led to anger in the affected societies and also action after action.

Our relations with Hamas concern the political wing of Hamas, and we will not apologize for that either. This cooperation has also helped to raise concerns about the hostages. We have no links with any military wings. I have already said that to my European colleagues and also in the US. But we have some different views. The Australian National Congress also recognized long before the Europeans or Americans that this apartheid policy must be abolished. That's why we have taken that position.

We need to understand what the fundamental problem with this is. We cannot allow people to be plundered, to have their homes taken away from them. This has to be solved. Am I in favor of people, of children being killed? Absolutely not. No, nobody should do that. That is the consistency in our politics. But I am against this obsession, this narrative, as if the whole problem started on October 7 and would end then. It didn't start on October 7, and it won't end then either. It started 40 years ago and it's still going on today.

Against this background, I am of the opinion - and I have also said this to the Chancellor - that we should now look to the future. We have a problem. Do we want to deal with history now, with the atrocities that have happened, or do we want to solve the problem now?

Solving the problem now means: the fighting must stop, the killing must stop. Then the whole international community - Germany, Malaysia and all neighboring countries - can ensure that there is no more violence, from any group, against anyone - not against Muslims, Christians or Jews. People must be able to live in peace. Thank you very much.

BK Scholz: I have already said it and I would like to repeat it again: Germany's position is clear. Israel has every right to defend itself against the terrorist attack by Hamas. We have always made that clear in recent days, weeks and months, and it remains so. Israel can rely on that.

At the same time, we have clear positions on further developments, and these have already been stated. Let me say this once again: we want more humanitarian aid to reach Gaza. We want the hostages to be released, unconditionally. We want there to be no unnecessary victims. That is why we have said very clearly what forms of military warfare are compatible with international law and what we find difficult.

I have spoken out on Rafah and on the need for a long-term peaceful perspective with a two-state solution that makes it possible for Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank to live peacefully in a separate, self-governing state alongside Israel - as a democracy in the region, and where the citizens of Israel can also rely on us. That is the perspective we are working for and what is at stake now. That is why we are working - despite the different assessments of the specific issue - on a peaceful perspective, which is necessary.

I would like to repeat what I have to say on the issue of supporting Ukraine in its defense. Germany is by far the country that is providing the most support for Ukraine - financially, but also in terms of arms deliveries. All in all, the deliveries to date and those promised amount to 28 billion euros and 30 billion dollars. That is a considerable sum. We have mobilized everything to ensure that Ukraine receives the necessary support from us - ammunition, artillery, tanks, air defence of various kinds, which is also highly efficient and very much appreciated. Our support is reliable and continuous. Ukraine knows this, and we hear time and again how much this great support is appreciated there.

As far as the one weapon system is concerned, I am of the opinion that it cannot be used without control in view of its effect and the way in which it can be used, but that the involvement of German soldiers is not justifiable, not even from outside Ukraine. I have therefore said that I do not consider the deployment to be justifiable and that it is therefore not a question of direct or indirect involvement, but of us being clear on this specific issue. My clarity is there. It is my job as Chancellor, as head of government, to be precise here and not to raise any misleading expectations. And my answers are correspondingly clear.

Question: Good afternoon, Excellencies! You both mentioned the situation in Gaza and said that we must look ahead to a two-state solution. But how much influence can this meeting have on a humanitarian ceasefire?

PM Anwar: Germany is an important country in Europe and has established good relations with Israel, and we have somewhat better relations with Palestine, with the Palestinian Authority and also with the political Hamas. Other Arab countries and neighboring states of Palestine and Israel are doing what they can. We should also be a little more positive. It is of course a chaotic situation, an uncertain situation. There is no easy solution. The Palestinians have suffered a lot. The Netanyahu government has also been very clear in its stance. There is no easy solution. We have to stop the killing of innocent people on both sides, the killing of civilians. We now need a permanent ceasefire and, ultimately, a two-state solution. This is also possible if the international community has the courage and determination.

I have said: sometimes you get really depressed when you have the feeling that this case has already been morally abandoned and that there is no real will from all countries to stop the war and find a solution. I am sure that the countries of the Middle East, the international community, Germany and the other parties involved want this peaceful solution.

BK Scholz: We would all have liked the start of Ramadan to have been accompanied by a longer-lasting ceasefire, which would have been linked to the release of the hostages by Hamas and also to an increase in humanitarian aid reaching Gaza. Having said that, the aim now is to bring this about as soon as possible. I believe that would be very important for everyone and could also create prospects for further developments. That is what is at stake now. We are in agreement with the American government and the European Union in everything we do. Many people around the world are also trying to work in this direction - as we have heard here, but this also applies to neighboring countries.

What we must prevent is an escalation of the war. We also warn against Iran or the Iranian proxies becoming more involved in this war than is already the case. This must be resolved soon. As I said, how this can be done is something that is very clear to me, to the European Union, to the USA and to many others, and it has also been mentioned here together.

Question: Mr. Prime Minister, you said that history should be left behind. But for the Israeli hostages, October 7 is still the present, also for their families. Regarding the talks you are holding with the political leadership of Hamas: What are you talking about? How much hope do you have that these hostages will be released soon? Can you also say something about what you saw on October 7 and the fact that these hostages are still being held by this terrorist violence?

Mr. Chancellor, you recently met the Pope, who has now caused controversy with his statements on the white flag, which Ukraine has taken to mean, as the Foreign Minister said, that the Church is behaving more or less as it did at the beginning of the 20th century, in other words that the Church did nothing against Nazi Germany at that time. How do you react to the Pope's statements?

PM Anwar: Thank you. I have already made my opinion clear. You cannot simply overlook the atrocities of the last four decades, and you cannot find a solution by being so one-sided, by looking only at one particular issue and simply brushing aside 60 years of atrocities. The solution is not simply to release the hostages. Yes, the hostages should be released, but that is not the solution. We are a small player. We have good relations with Hamas. I have told the Chancellor that, yes, I too would like the hostages to be released. But is that the end of it, period? What about the settlements, the behavior of the settlers? No, it goes on every day. What about the expropriations, their rights, their land, their dignity, the men, the women, the children? Is that not the issue? Where is our humanity? Why is there this arrogance? Why is there this double standard between one ethnic group and another? Do they have different religions? Is it because of that? Why is there a problem?

Yes, we want the rights of every single person to be recognized, regardless of whether they are Muslim, Jewish or Christian. I am very clear on that. But of course I cannot accept that the issue is focused on just one case, on one victim, and that the thousands of victims since 1947 are simply ignored. Is humanity not relevant? Is compassion not relevant? That is my point. Do I support any atrocities by anyone towards anyone? No. - Do I want hostages to be held? No. But you can't look at the narrative in such a one-sided way.

You can ask if I disagree with some subgroups. But that's not the way to solve the issue. We have to be fair, just, and find an amicable solution that is just, that is fair.

BK Scholz: Once again what I have already said: Germany has a special and good relationship with Israel. That is very important to us. That's why Israel can also rely on us. You have a clear position on what is necessary now. That includes the release of the hostages. That includes humanitarian aid. It includes the prospect of a two-state solution. I have already spoken about this, I just want to mention it again here. This is also important for us. We were very supportive of the founding of the state of Israel, and German policy will continue to develop along these lines.

As far as the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine is concerned, Germany's position is very clear: Ukraine has the right to defend itself, and Ukraine can rely on us to support it in many, many ways. I have already said that we are very far ahead when it comes to the volume and quality of the arms supplies we have provided. That is also true. That is why, of course, I do not agree with the position quoted.