Confederation of Latin American and Caribbean Nations as a strategy for integration with Asia and Africa

by Isaac Elías González Matute

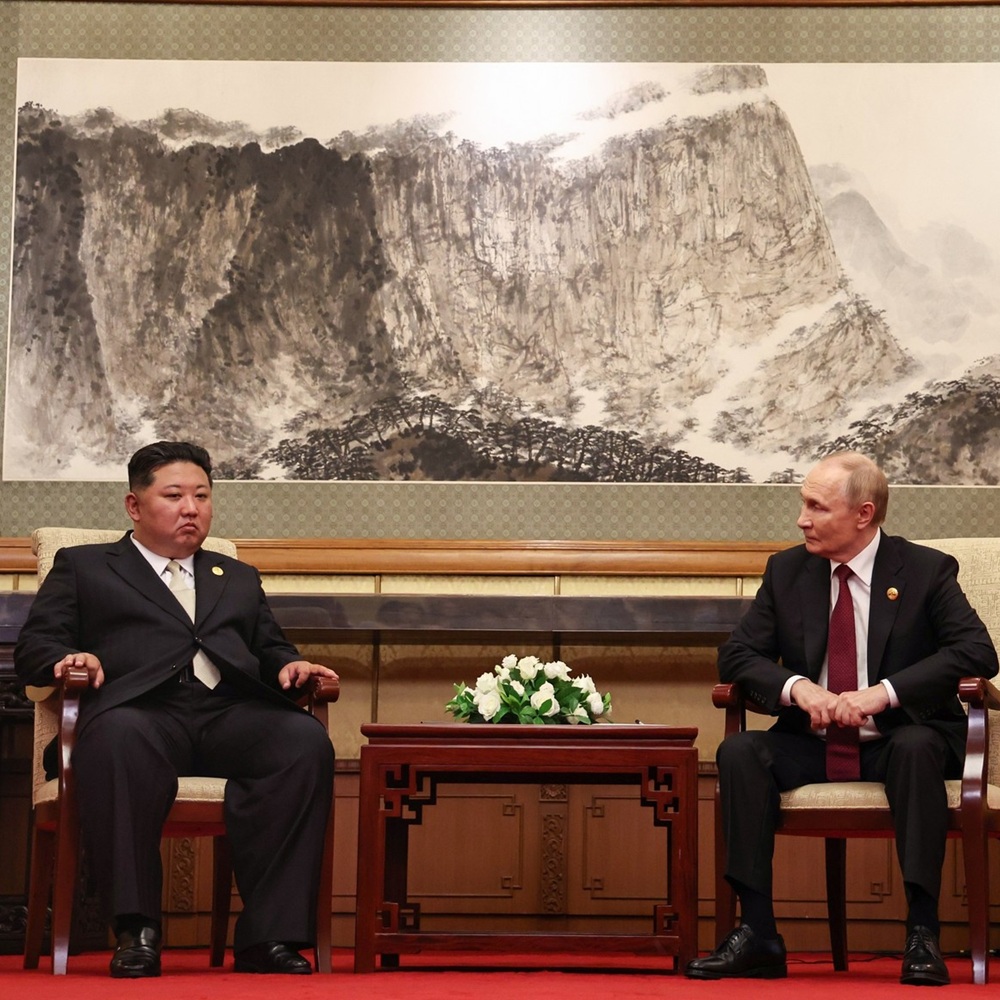

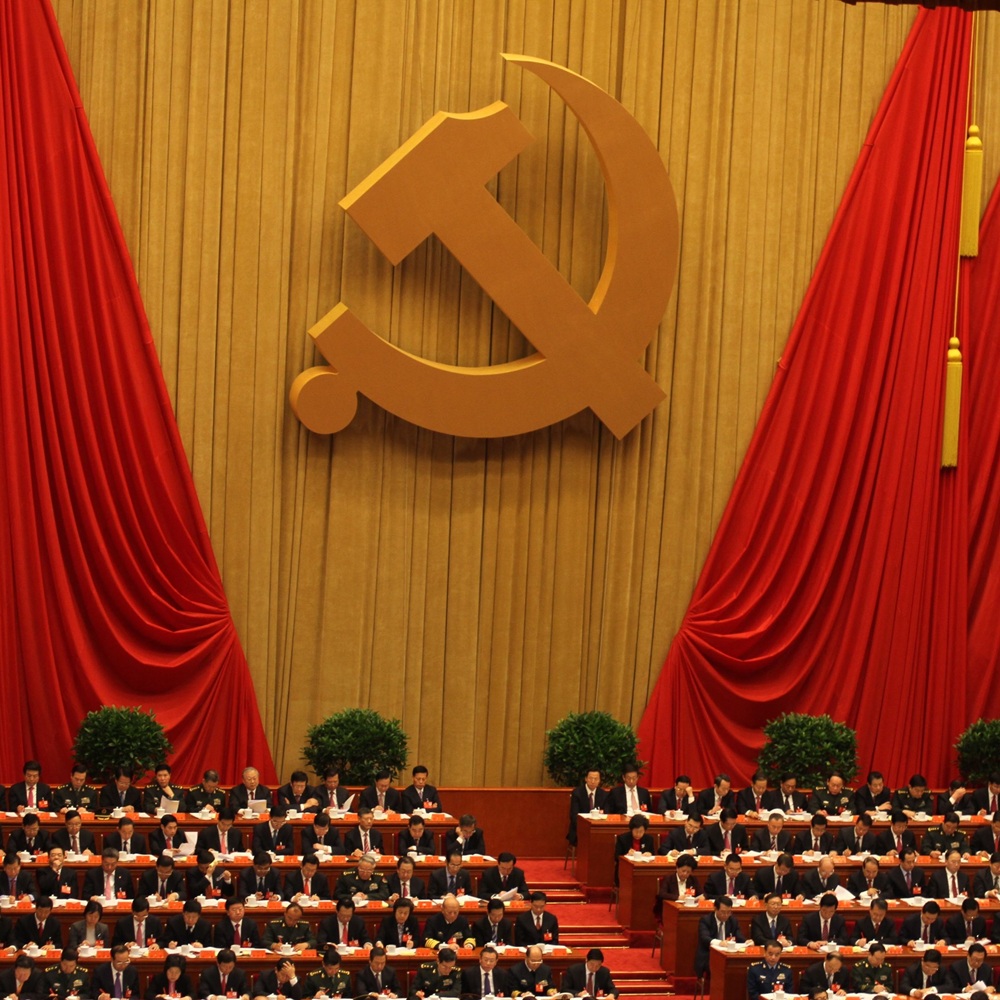

Abstract This article analyzes the challenges and threats to global peace and stability, derived from the unipolar geopolitical vision of the United States and the application of the so-called “Donroe Doctrine”, promoted during the Trump administration and characterized by the “Maximum Pressure” strategy promoted by the America First Policy Institute. Through a methodology of documentary review of primary and secondary sources, together with a prospective analysis of risk trends, the strategic and leading role of CELAC in the defense of the interests of Latin America and the Caribbean is dimensioned, highlighting how this organization opens opportunities to strengthen trade relations with Asia and Africa, contributing to the construction of a multipolar world order by promoting initiatives such as China's Belt and Road as an alternative mechanism to the global economic war of the United States and its “US-CUM” project, framed in its foreign policy based on national security interests. Introduction 21st-century geopolitics has undoubtedly been characterized by strong pragmatism in the exercise of states’ foreign policy, balancing between two visions — specifically between the Unipolar Geopolitical Vision and the Multipolar Geopolitical Vision — which have categorized the praxis of international relations of the so-called Global North and Global South, respectively; a context that clearly shows a fervent struggle for political control of resources and for hegemony, where the United States competes for global supremacy with emerging poles of power such as Russia and China. Given the current international scenario, it becomes increasingly imperative to identify and understand both the needs and the challenges for the planet’s sustainable development, from a global perspective in all areas (economic, political, social, geographic, cultural, environmental, and military). In this regard, the present research prospectively analyzes the administration of President Donald Trump as part of the multidimensional threats that the U.S. represents not only for Latin America and the Caribbean but also for Africa and Asia, considering the impact of current U.S. foreign policy both on the American continent and for Africa and Asia. All of this is with a view to highlighting, through debate, the importance of rethinking CELAC as an international organization that systematically advances in a transition process from “Community” to “Confederation,” as an intergovernmental entity with the capacity to confront the threats of a unipolar geopolitical vision foreign policy, and in line with the goals established as development projects under the so-called “CELAC 360 Vision” [1], aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda, adopted by the United Nations (UN). Regarding the referred geopolitical transition, it is worth noting, as Guendel (2024) states: “The rising multipolarity will provoke, starting from this first decade of the 21st century, the emergence of historical events that mark the reaction to the expansion of Western geopolitical power to those old regions that were under another geopolitical influence. Among the most notable events, we must consider the processes of de-dollarization of the world economy, the war in Ukraine, the tension in the Taiwan Strait, and, of course, the war in Palestine. Under this reference, it is possible to characterize the current international geopolitical scenario as a moment of transition between the previous form of unipolar power and the new multipolar relations (123) [2]. Building on the above, the current geopolitical transition is a systemic process sustained by the multipolarity of international relations, driven by the struggle for power and the quest for economic dominance in both domestic and international markets. This has given rise to a growing trend in states’ foreign policy toward the construction of a multipolar world, where territorial governance over strategic resources forms part of the necessary geopolitical counterweight in regional dialogue, cooperation, and integration to face the challenges of the present century. The changes in the world order require Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia to promote an idea of continental unity, framed within an anti-imperialist mindset, allowing progress toward Latin American, African, and Asian continentalism, compatible with the multipolar geopolitical vision, under the sustainable development approach put forward through the BRICS. Regarding this last international actor, Guendel (2024) notes: “In the development of a new phase of the globalization process after the end of the Cold War — what was geopolitically a new scenario for consolidating unipolar power relations — new lateral actors emerged, the so-called BRICS, which, by proposing alternative ways of thinking and economic relations favorable to Third World countries, would foster the emergence of a new global geopolitical scenario of multipolar relations (123). According to this scenario, the trend toward multipolarity in international relations —strengthened by globalization and technological advancements — will allow for the consolidation of a multipolar world, though not without first becoming a causal factor of various conflicts and challenges on a global scale, specifically in all spheres of power (economic, political, social, geographic, cultural, environmental, and military). Hence the importance of formulating a strategy for regional integration of Latin America, Asia, and Africa that aligns with global sustainable development plans — such as China’s Belt and Road Initiative — which, combined with the BRICS, constitute two fundamental pillars in strengthening the multipolar world. However, this will also accentuate the differences in geopolitical interests between the strategic agenda of the Global North (led by the U.S. through the G7) and that of the Global South (BRICS countries) regarding the projected economic growth of each. Having this in mind, the present research aims to analyze the challenges and threats to global peace and stability as a consequence of the U.S. unipolar geopolitical vision and the application of the so-called “Donroe Doctrine,” promoted by President Donald Trump and the policies advanced by his main think tank, the America First Policy Institute (AFPI), characterized by the “Maximum Pressure.” Development U.S.: Foreign policy oriented toward a new global fundamentalism The new White House administration, under the presidency of Donald Trump, challenges the so-called conservative Establishment [3] in the U.S., and according to Myriam Corte (2018), in her article on “Analysis of the U.S. ‘Establishment’” [4], the following statement is mentioned: “The residence of the current president is the site that houses political power, but at the same time reflects migratory power, since it is a construction built in the 18th century by African slaves, based on Irish architecture. As for the cabinet, it is made up of wealthy white men, who are responsible for administering power, but in the current administration some members have been accused of domestic abuse and misogynistic practices; therefore, it is important to identify whether Trump represents that old, conservative, and rigid establishment, or if there is any change” (1). According to what has been stated, there is undoubtedly a perception of a different stance associated with the “Deep State” Establishment in the U.S., with relevant structural changes that have a strong impact on both domestic and foreign policy. An example of this, according to Myriam Corte (2018), is represented in the very fact that: “Another variant is the Bible study group that was formed in the White House, as well as the group of fellows made up of 147 young people between the ages of 21 and 29, with a characteristic profile: all are wealthy individuals, among them the son of the president of the World Bank, who represent the new generation that will inherit power…” (1). In this context, the U.S.’s status as a major power revolves around a scenario of geopolitical conflict, even prioritizing its national interests over those of its main strategic allies, as a consequence of the systemic deterioration of its hegemony vis-à-vis Russia and China. This has generated hostile political actions as strategies to justify its territorial ambitions, in an attempt to counter the exponential growth of the BRIC and the crisis this represents for the global dollar system. A clear example of some hostile political actions is reflected in what happened with its European (NATO) partners recently, as well as with Canada, Mexico, and Greenland, becoming part of the geopolitical pragmatism promoted by the Donald Trump administration. Now, in direct relation to the unipolar geopolitical vision that characterizes U.S. foreign policy, it oscillates between defending the interests of the conservative Establishment and the postulates and ideals promoted by the AFPI [5], which maintain a clear influence in the conduct of U.S. foreign policy, acting as a think tank. Regarding this matter related to the influence of AFPI in the Donald Trump administration, it is worth mentioning some aspects associated with the practice of U.S. foreign policy for a better understanding of its current dynamics, which revolve around a new global fundamentalism with a marked unipolar geopolitical vision. Among them, we have the following: New global fundamentalism against the conservative national security establishment The AFPI serves as the main think tank for the Trump administration, according to Seibt (2024), who in his article “The America First Policy Institute, a discreet ‘combat’ machine for Donald Trump” [6], states the following: “America First” is often associated solely with Donald Trump’s isolationism. But behind the scenes, it is also linked to an ultra-conservative think tank with growing influence, the America First Policy Institute (AFPI)” (1); a fact that justifies the appointments made before and after Donald Trump’s swearing-in as President of the U.S., as he has been using an increasingly influential group in high-level decisions, subtly and systematically modifying changes in strategic agendas from the so-called “Deep State,” starting from what Seibt (2024) also refers to: “…the election of Brooke Rollins marks the consecration of AFPI’s influence, of which she is president, and which has been described by the New York Times as ‘a group as influential as it is little known’ in the orbit of Trumpism… Brooke Rollins is not the only person from AFPI that Donald Trump has chosen for his future government. Linda McMahon, chosen to be Secretary of Education, is the director of this think tank. And let us not forget Pam Bondi, who has been called to replace the too-controversial Matt Gaetz as Attorney General, and who oversees all the legal matters of the America First Policy Institute” (para. 5). In this context, there is clear evidence of AFPI’s influence within the Trump administration; therefore, to understand where the unipolar geopolitical vision recently adopted by the U.S. is headed — together with its prospective analysis — it is necessary to understand, from the very foundations of AFPI, how this organization envisions the path of what it calls, from a supremacist perspective, “America First.” To this end, it is enough to review the main AFPI website [7], where both its vision and analysis of what the U.S. should be, as well as how it should approach the exercise of foreign policy, are broken down and organized — with a curious detail that sets it apart: placing the interests of the American people above the interests of the conservative National Security establishment, stimulating the need to create a nation different from what they consider a “theoretical United States.” As AFPI (2025) states and describes: The Center for American Security at the America First Policy Institute defends Americans rather than a “theoretical United States” imagined by Washington’s national security establishment. The exercise of American power requires a clear justification, and an “America First” approach ensures that such power is used for the benefit of Americans. To promote this objective, the Center seeks to ensure the rigorous advancement of policies that constitute an authentically American alternative to the increasingly obsolete orthodoxy of Washington’s foreign and defense policy… (para. 2). As outlined, AFPI both promotes and warns about the exercise of power, prioritizing U.S. interests, as long as these remain distant from what it considers the “obsolete orthodoxy of foreign policy” that has characterized the U.S. for decades and centuries. In this sense, the likelihood increases of perceiving the presence or formation of a different establishment in the U.S., one that rivals the Anglo-Saxon conservatism rooted since the nation’s very founding. Domestically, the perception of a new global fundamentalism in U.S. foreign policy grows — one with an even more marked unipolar geopolitical vision of an imperialist nature — based on what AFPI (2025) doctrinally dictates in terms of foreign policy: The phrase “America First” refers to an approach rooted in the awareness of the United States’ unique role in the world and its unparalleled ability to do the most for others when its people are strong, secure, and prosperous. It means that any commitment of American lives or dollars abroad must bring concrete benefits to the American people. Every investment of U.S. resources must generate a substantial security benefit (para. 3). From this, it is possible to infer the direction of the U.S. strategic agenda under the current administration and doctrinally supported by AFPI as its main think tank. However, the deep changes that are occurring — both inside and outside the U.S. — and how the global economic and financial situation fluctuates because of these changes, in a certain way, compel major economies to reconsider new mechanisms for economic and financial coordination and cooperation. This includes strengthening regional integration frameworks that allow them to navigate the ongoing process of reconfiguring the current world order, laying the groundwork for the construction of a multipolar world. Proxy Control of Global Territorial Governance, Backed by the “Donroe Doctrine” The exercise of current U.S. foreign policy, characterized by a unipolar geopolitical vision under the new Trump administration, is the result of the application of a doctrine carefully designed and reformulated from its dogmas, supported by a strong religious fundamentalism and associated with racial supremacism; wherein the U.S. seeks to perpetuate its global hegemony by returning to its original imperialist character. All of this turns the exercise of U.S. power toward National Security, but with a practical approach different from the so-called “obsolete orthodoxy of conservative foreign policy.” As AFPI (2021) has emphasized since its founding: Religious freedom is a fundamental human right guaranteed not only in the Constitution of the United States but also in Article 18 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It is a natural right inherent to all of humanity (para. 3). With the above, at first glance, AFPI appears to delineate its religious fundamentalism, oriented toward the promotion of a new global fundamentalism through the exercise of foreign policy that justifies its actions in favor of U.S. supremacist interests, in line with what AFPI (2021) reiterates as its mission on its platform: AFPI exists to promote policies that prioritize the American people. Our guiding principles are freedom, free enterprise, national greatness, U.S. military superiority, foreign policy engagement in the interest of the United States, and the primacy of American workers, families, and communities in all we do (para. 1). To this, we must add the disposition — regarding national security — of driving U.S. supremacism through the application of Hard Power [8], economic warfare, and the increased implementation of Unilateral Coercive Measures (UCMs) against any country that contravenes U.S. interests, by perpetuating interventionist policy in all spheres of power (economic, political, social, geographic, cultural, environmental, and military). An example of the above is referred to by AFPI (2025) on its website [9], as follows: The American victories in World War II and the Cold War established our country as “the last best hope for man on Earth.” The cause of freedom everywhere in the world depends on a strong United States. With our country secure, we can, with greater confidence, promote American security abroad. U.S. security is exemplified by a strong military, fair trade agreements, alliances that are equitable, aggressors who are isolated, and those who harm us, destroyed. The AFPI views American security abroad as a prerequisite for peace at home: always putting American interests first. This includes moving away from endless and unnecessary wars to rebuild the homeland, while also understanding our indispensable role in maintaining a peaceful world… (para. 4). With a brief reading of the above, it is possible to see at first glance the practical description of current U.S. foreign policy, starting from the fact of recent attempts to end the Ukrainian conflict; however, skepticism when addressing both the geopolitical feasibility and the reliability of the proposals made by the Trump administration reveals a hidden objective, particularly associated with proxy control of global territorial governance through hostile policies and the use of the government itself as a weapon. An example of this is the stimulation of a trade war by the U.S. against Canada, Mexico, and the European Union (NATO allies), all with the aim of establishing as a rule the use of Hard Power for political persuasion over strategic resources — an example of this being the recent (and forcibly) signed rare earths agreement by Ukraine — in favor of the United States. U.S.-CUM, a New Nation-State and Persuasive Technology: Utopia or Global Geopolitical Threat? Geopolitical changes in the 21st century are advancing in parallel with technology, the economy, and global energy interdependence. For this reason, the use of Persuasive Technologies [10], through various media and information channels, plays a fundamental role in creating opinion frameworks and the mass manipulation of perceptions on a global scale. In other words, in the Era of Disinformation, technology is the primary tool, stemming from the communication needs of modern society. In this regard, Tusa et al. (2019) state the following: “…fake news has always existed. What is happening now is a greater emergence on open and free access platforms, which causes this type of information to grow exponentially in a matter of seconds. Therefore, fake news creates a wave of disinformation, a fact that motivates academia and civil society to counter it, to achieve the return of good journalism and truthful information” (20). [11] In this context, current disinformation processes respond to pre-established objectives by power poles linked to fluctuating geoeconomic interests in the world order, in which the Global North with a unipolar geopolitical vision and the Global South with a multipolar geopolitical vision are in open confrontation. In relation to this, Valton (2022) points out: “…economic globalization, finance, and the development of new technologies have opened spaces for the new geoeconomy. Thus, geoeconomy as part of the process of change plays an essential role that affects international relations, with an impact on international trade, global markets, and conflicts in the quest for capital accumulation. Geopolitical interests are closely linked to the economic gains of major capitalist powers and transnational corporations in their eagerness to increase their revenues, maintain and expand their area of influence in other regions, at the expense of the indiscriminate exploitation of the natural resources of underdeveloped countries, with high poverty rates and environmental damage” (2). [12] Now, considering the unipolar geopolitical vision of U.S. foreign policy and the doctrinal influence of the AFPI in the new Trump administration, there is a curious growing communication campaign on different digital platforms, specifically associated with persuasive technologies, that fosters the perception of the creation of a new State called U.S.-CUM. While this corresponds to a very subtle disinformation campaign and somewhat utopian in nature, it is nonetheless surprising that, in the facts and actions of the new White House administration, they have not stopped flirting with certain ideas related to the mentioned State in question. To be more specific, the U.S.-CUM is a utopian idea of a territorial expansion of the current United States, adding the territorial spaces of Canada and Mexico with the goal of increasing the economic, political, financial, and military capacities of the U.S., to counter emerging powers and prevent the consolidation of a multipolar world. An example of this can be found in some posts made on the Reddit platform, a social network popular among the U.S. population, similar to Instagram, X, TikTok, and Facebook, among others. The U.S.-CUM utopia has now moved from a mere concept to a possible threat to global geopolitics, the moment the foreign policy of the Trump administration suggests the possibility of territorially adding Canada, turning it into the 51st state of the United States. Colvin (2025), in his AP article titled “Trump says he is serious about making Canada the 51st U.S. state,” refers to the following: President Donald Trump said he was serious about wanting Canada to become the 51st state of the United States in an interview aired Sunday during the Super Bowl pregame show… The United States is not subsidizing Canada. Americans purchase products from the resource-rich nation, including raw materials such as oil. Although the goods trade deficit has grown in recent years to $72 billion in 2023, it largely reflects U.S. imports of Canadian energy… (paras. 1-4). [13] In relation to the same policy undertaken with Canada, the Trump administration began a very dangerous strategy against its territorial neighbors, with the following actions: declaring Mexican drug cartels as terrorist groups (knowing how the U.S. has manipulated the concept of terrorism to justify military interventions), implementing migrant deportation policies, waging a fight against fentanyl, and additionally launching a tariff war with both Mexico and Canada. It has also reiterated its intention to annex Greenland, accompanied by threats of tariffs and a trade war against Denmark and other EU countries, including undermining the existence of NATO. All the above is carried out under the close advice and influence of the AFPI, clearly reflected in its supremacist doctrinal positions and aspirations to create a large imperialist nation. An example of these ambitions has been openly published by various international media outlets, including the news channel FRANCE24. In this outlet, Blandón (2025) refers to the following: During a meeting with NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte, U.S. President Donald Trump reiterated that control of Greenland is necessary to improve international security, while once again confirming his interest in annexing this territory… Outgoing Greenland Prime Minister Mute Egede responded on the social network Facebook: “The U.S. president has once again raised the idea of annexing us. Enough is enough!”, and added that he will call on the leaders of all parties to convince them to prevent it… (paras. 1, 2). In other words, it is appropriate to infer that the direction and intentionality of the foreign policy of the new Trump administration is aimed at territorial expansionism and the promotion of proxy control of global territorial governance, supported by the “Donroe Doctrine” and enhanced through the use and development of Persuasive Technology, aligned with a global strategic agenda (influenced by the AFPI), which seeks to counter the strengthening of a multipolar world and perpetuate U.S. imperialist hegemony under a global supremacy fundamentalism. CELAC as a Geopolitical Counterweight to the Real Threat of the U.S. and Its New Imperialist Format for Hegemonic Survival The Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), as an intergovernmental organization, currently acquires strategic value for the entire continent and its sustainable development, within the framework of creating new mechanisms for coordination, cooperation, and regional integration with Africa and Asia — especially China — through the Belt and Road Initiative, considering the entire current geopolitical context where markets play a predominant role in defining internal policies and in directly influencing the strategic agendas of each nation's foreign policy, according to constantly changing global challenges, heightened by the stance adopted by the Global North, led by the U.S., against the Global South, led by BRICS countries. Once the real threat posed by the U.S. has been identified — based on the unipolar geopolitical vision that has characterized the exercise of its foreign policy — this is compounded by the supremacist trend in implementing Unilateral Coercive Measures (UCMs) [14] against free and independent nations that, upholding the principle of self-determination, do not submit to or share the interests of the Anglo-Saxon establishment, promoted by the new U.S. administration. Now then, conducting a prospective analysis of how and on what grounds the U.S. sustains and describes its current hegemonic behavior, it is possible to predict, with certain elements and data, what its courses of action will be — courses that Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as Africa and Asia (especially China), should consider. Among these, the following stand out: Territorial Expansion of the U.S. Trade War The current trade war declared between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico — initially through the reciprocal imposition of tariffs — considering the influence of the AFPI as a U.S. Think Tank, is clearly perceived as territorial expansion, in search of proxy control over territorial governance previously mentioned, of all strategic resources in Latin America and the Caribbean. This comes because of the fiscal, economic, and financial weakening the U.S. is experiencing through the increase of public debt, which is practically unsustainable. In this sense, the actions taken by the Trump administration in appointing certain cabinet positions can be understood to some extent. However, it is curious and at the same time causal that many appointments obey and are related — directly and indirectly — to the training of officials associated with and linked to the AFPI, as part of its strategic objective. An example of this are the words of Colonel Robert Wilkie, co-chair of the Center for American Security, member of the AFPI, quoted by King (2025) in his press article titled “AFPI Welcomes President Trump’s Renewal of the American Dream”, where the following was stated, making direct reference to peace through strength: President Trump proclaimed that America is back, which means our Armed Forces are back: the greatest force for peace in the history of the world. He has restored the highest combat standards so that our soldiers fight, win, and return home to their loved ones as soon as possible. President Trump has restored the place of honor our warriors hold in the hearts and minds of the American people. He has restored America’s deterrent power and told the world that the most powerful words in the language are: “I am an American citizen.” Our borders are stronger, our seas safer, and every wrongdoer knows that the eagle is watching them. (para. 6) The above statement does not set aside its imperialist and supremacist character, denoting the philosophical and doctrinal thinking deeply rooted in the officials who hold government functions at all decision-making levels, promoting pro-U.S. policies that disrespect international law and encourage the establishment of a rules-based world order, with full disregard for the international rule of law. This is, in fact, a very complex and dangerous geopolitical situation, which threatens not only the self-determination of peoples, but also the ability to advance in areas of coordination, cooperation, and integration to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted in the United Nations 2030 Agenda, to which CELAC countries adhere through the implementation of development plans seeking mutual benefit. Now then, the world order is in permanent change, with a tendency toward the consolidation of a multipolar world because of the crisis of capitalism and the Anglo-Saxon economic model represented in the Bretton Woods System. This situation favors the opening of new mechanisms supported by the multipolarity of international relations, depending on the behavior of the world economy, as a result of the policies of both the U.S. and emerging powers—especially the BRICS countries. However, it is precisely the economic pulse that will redefine the hostile actions of the U.S. in defense of its global hegemonic power, equally and in parallel influenced by the energy capacities of the world powers in conflict — an element that is preponderant in geopolitical influence. An example in this chapter is Russia’s advantage in gas and oil during the Ukrainian conflict. The exponential economic growth of the BRICS compared to the G7 is the clearest expression of the multilateral influence trend of member countries, in line with the multipolarity of international relations, where the geopolitical positioning of both the Global North (G7) and the Global South (BRICS) can be clearly observed. This economic and financial disparity accelerates the weakening of the Bretton Woods System and, consequently, the collapse of the dollar system within the Anglo-Saxon economic model, leading to the loss of hegemonic influence of the Global North countries — especially the U.S. as its main exponent. Other data are relevant when conducting a prospective analysis, with the aim of identifying growth and sustainable development opportunities, as well as understanding the challenges to achieving strategic objectives for comprehensive development by nations. Among the data to consider in the prospective analysis, we have the following chart, associated with excessive global consumption in the 21st century compared to the 20th century: According to the chart on excessive global consumption, in only six years of progress into the 21st century, modern society has exceeded more than half of what it consumed in the 20th century, with a 75% increase above the average recorded over the last 100 years — a truly alarming percentage with a tendency to increase, as a consequence of economic activity, technological advancement, and the increase of armed conflicts worldwide. Within this context, the U.S. will increasingly seek to influence countries that significantly represent an economic interest in terms of territory, population density, manufacturing and industrial capacity, and geographic position. Through proxy control of territorial governance, it will aim to increase its hegemonic capacity in the economic and financial spheres against its main geopolitical rivals in the struggle for global supremacy — namely Russia and China — whose multipolar geopolitical vision entirely rivals the unipolar geopolitical vision of U.S. foreign policy. Given this scenario, CELAC presents a fundamental characteristic that allows it to move forward as a geopolitical counterweight to the U.S., broken down as follows:Territorial extension: all member countries together cover an enormous territorial space rich in strategic resources, with common areas of influence and mutual interest for sustainable development. Shared future, based on history, language, customs, and other cultural expressions that strengthen Latin American and Caribbean identity, which can be leveraged in the processes of regional consultation, cooperation, and integration with Africa and Asia. The increase in the hostile trend of U.S. foreign policy worldwide will require greater effort from CELAC to advance in consolidating full regional integration. However, the current progress of the intergovernmental organization has been limited to certain and specific areas, namely the economic, cultural, social, and political spheres of its members. Transition toward the Confederation of Latin American and Caribbean States as a strategy for geopolitical counterbalance and sustainable development For CELAC to consolidate itself as a geopolitical counterweight to U.S. hegemonic ambitions in the region, it must be grounded in the exercise of a foreign policy with a multipolar geopolitical vision, compatible with the mutual sustainable development interests of the Global South. In this regard, Palacio de Oteyza (2004), in his essay "The Imperial Image of the New International Order: Is This Political Realism?" states the following: “The second realistic image of the international order, partially compatible with the geoeconomic image, consists of a return to a traditional multipolar system of balance of power, but with a decisive weight given to the military factor. The multipolar system is characterized by the absence of a hegemon and a flexibility of alliances among the great powers, aimed at restraining any potential challenger” [13]. In this context, the geopolitical counterweight that CELAC needs to confront the U.S.’s hegemonic ambitions in the region — and even globally — is regional integration in other areas not currently contemplated by the Community of Nations due to its nature. That is, increasing integration in the military, geographic, and social spheres through the transition toward a confederation of nations would enhance international relations capabilities, contributing to the adoption of deterrent measures for the prevention of armed conflicts and even facilitating its integration into other centers of power with a multipolar geopolitical vision, such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), to further strengthen relations with both Russia and China and their respective sustainable development plans. Economic opening and new formulas for regional integration with Africa and Asia An economic opening is the result of the globalization process, the advancement of new technologies, and the effects of the exercise of states’ foreign policies in accordance with their interests and the geopolitical vision they adopt, for geopolitical analysis that enables the identification of risks, threats, and opportunities in the international arena. That said, within the framework of regional integration, CELAC must also prioritize investment sectors for the establishment of common development interests among CELAC, Africa, and Asia. One of the most notable current realities is the fact that the Global South’s economy began systematically, setting challenges and then experiencing growth in less time compared to the growth of the G20, led by the U.S., with China taking the lead according to the percentage value recorded in 2024. In this scenario, CELAC, by reconsidering its transition toward a Confederation of Latin American and Caribbean States, would allow for greater autonomy in its integration into the global architecture implied by the strengthening and consolidation of the BRICS at the global level as an alternative system to the Bretton Woods System. In doing so, advances toward strengthening regional integration — embedded within a new multipolar world, with the combined capabilities of the Global South — can become, more than a reality, a necessity to confront the real threats posed by the U.S., serving as a geopolitical counterweight and a tool for insertion into the multipolar world through continental alliances between Latin America and the Caribbean, with Africa and Asia. Conclusions It was possible to assess the leading role of CELAC and its strategic nature in defending the regional interests of Latin America and the Caribbean, opening a world of opportunities in trade relations with Asia and Africa for the construction of a multipolar world through the promotion of China’s Belt and Road Initiative as an alternative mechanism to confront the U.S. economic war on a global scale and its project to create the so-called “U.S.-CUM”, as part of its foreign policy based on its national security interests. In this regard, in an environment of geopolitical changes and international crisis, as part of the transition process toward the consolidation of a multipolar world, CELAC can promote or drive significant advances aimed at the creation of a Confederation of Latin American and Caribbean Nations (CONLAC) as part of a strategy for integration with Asia and Africa, considering the multipolar geopolitical vision shared by the Global South, where the concept of shared development represents a key point for international dialogue and cooperation — specifically in the economic, social, political, geographic, cultural, environmental, and military spheres. All of this would serve to act as a geopolitical counterweight to the threats and global challenges promoted by the U.S., in the exercise of its unipolar geopolitical vision in foreign policy, of an imperialist, hegemonic, and supremacist nature. Notes [1] Fuente: https://celacinternational.org/projects/[2] Revista Comunicación. Año 45, vol. 33, núm. 1, enero-junio 2024 (pp. 120-133). Fuente: https:// www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1659-38202024000100120[3] Conjunto de personas, instituciones y entidades influyentes en la sociedad o en un campo determinado, que procuran mantener y controlar el orden establecido. Fuente: https://dpej.rae. es/lema/establishment[4] https://gaceta.politicas.unam.mx/index.php/poder-estadounidense/[5] https://americafirstpolicy.com/issues/security/national-security-defense[6] https://www.france24.com/es/ee-uu-y-canad%C3%A1/20241126-el-america-first-policy-institute-una-discreta-m%C3%A1quina-de-combate-de-donald-trump[7] https://americafirstpolicy.com/centers/center-for-american-security[8] El poder duro se da cuando un país utiliza medios militares y económicos para influir en el comportamiento o los intereses de otras entidades políticas. Es una forma de poder político a menudo agresiva, es decir, que utiliza la coerción. Su eficacia es máxima cuando una entidad política la impone a otra de menor poder militar o económico. Fuente: https://www. jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/what-isthe-difference-between-hard-power-and-softpower-1608095574-1[9] https://americafirstpolicy.com/centers/center-for-american-security[10] La tecnología persuasiva está concebida para permitir que los usuarios voluntariamente cambien sus actitudes o comportamientos por medio de la persuasión y la influencia social. Al igual que la tecnología de control, utiliza actuadores y un algoritmo de influencia para ofrecerle información eficaz al usuario. Fuente: https://osha.europa.eu/es/tools-and-resources/eu-osha-thesaurus/term/70213i#:~:text=Context:,ofrecerle%20informaci%C3%B3n%20eficaz%20al%20usuario[11] https://revistas.usfq.edu.ec/index.php/perdebate/article/view/1550/2661[12] Fuente: https://www.cipi.cu/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/1-elaynevalton.pdf[13] https://apnews.com/article/trump-canadagolfo-america-super-bowl-bret-baier-musk-cc8848639493d44770e60e4d125e5a62[14] Medidas Coercitivas Unilaterales.[15] Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, núm. 64, p. 7-28 References Colvin, J. (2025, 9 de febrero). Trump dice que habla en serio al afirmar que Canadá sea el estado 51 de EEUU. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/trump-canada-golfo-america-super-bowl-bret-baier-musk-cc8848639493d44770e60e4d125e5a62Corte, M. (2018, 7 de mayo). Análisis del ‘establishment’ estadounidense. Gaceta UNAM. https://gaceta.politicas.unam.mx/index.php/poder-estadounidense/Guendel Angulo, H. (2024). Escenarios de transición: De la geopolítica mundial unipolar a la multipolar. Revista Comunicación On-line. https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1659-38202024000100120Palacio de Oteyza, V. (2003). La imagen imperial del nuevo orden internacional: ¿es esto realismo político? Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, (64), 7-28. https://www.cidob.org/publicaciones/la-imagen-imperial-del-nuevo-orden-internacional-es-esto-realismo-politicoSeibt, S. (2024, 26 de noviembre). El America First Policy Institute, una discreta máquina de "combate" de Donald Trump. France24. https://www.france24.com/es/ee-uu-y-canad%C3%A1/20241126-el-america-first-policy-institute-una-discreta-m%C3%A1quina-de-combate-de-donald-trumpTusa, F., & Durán, M. B. (2019). La era de la desinformación y de las noticias falsas en el ambiente político ecuatoriano de transición. Perdebate. https://revistas.usfq.edu.ec/index.php/perdebate/article/view/1550/2661Valton Legrá, E. (2022). La geopolítica de la tecnología: una visión sistémica. CIPI. https://www.cipi.cu/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/1-elaynevalton.pdfZelada Castedo, A. (2005). Perspectiva histórica del proceso de integración latinoamericana. Revista Ciencia y Cultura, (17), 113-120. Universidad Católica Boliviana San Pablo, La Paz, Bolivia.